The affordable and efficient postal service we take for granted was a modern innovation, pushed by a global wave of reform starting in 1840. By 1874, newly streamlined national systems were connected through a global body, now known as the Universal Postal Union, which has since helped make sending international mail cheap and easy.

A rising chorus of critics, though, claim that the UPU has lost its way. Its politicized and arcane system of pricing agreements has limited competition from private companies and turned national posts against each other, while subsidizing small-parcel e-commerce from developing countries like China. It’s the reason you can order a memory card from Nanjing to Oslo for less than the price of an iced latte—but the real cost of those cheap Chinese trinkets is much greater.

The idealistic foundations of the UPU can be traced back to the work of Sir Rowland Hill. Born in Worcestershire in 1795 to a long line of freethinkers (his grandfather once saved an accused witch from drowning by a mob), Hill was, as a brother put it, “born to a burning hatred of tyranny.” He expressed his love of freedom mostly by working to broaden access to information and communication. He argued for cheaper newspapers, wrote a book on educational reform, and invented a high-speed printing press before discovering his real life’s work: reforming England’s postal system. At the time, the posts were so unwieldy and expensive that elaborate fraud was common, most notably the misuse of the mail privileges of members of Parliament, a practice known as “franking.”

Hill began agitating for lower rates and convenient payment (he was the inventor of stamped mail), arguing—with help from calculations by none other than Charles Babbage—that lower rates would actually increase revenue. But his motivations were only partly fiscal: “The more serious evil,” he later wrote of the old system, “resulted from the obstruction thus raised to the moral and intellectual progress of the people.” For Hill, postal reform held all the edifying promise that later innovators would attribute to the Internet.

Hill’s reforms, creating what was known as the “penny post,” were implemented in England in 1840, and succeeded so completely that they were quickly and widely imitated. Stamped mail was introduced to the United States in 1847, for instance, greatly easing communication during the Civil War and the Gold Rush.

But the international post was still labyrinthine—Germany alone was signatory to 17 bilateral postal agreements as of 1873. Mail that traveled through multiple countries had to bear postage from each, with rates variable by distance and weight, measured and assessed separately in the units of each country.

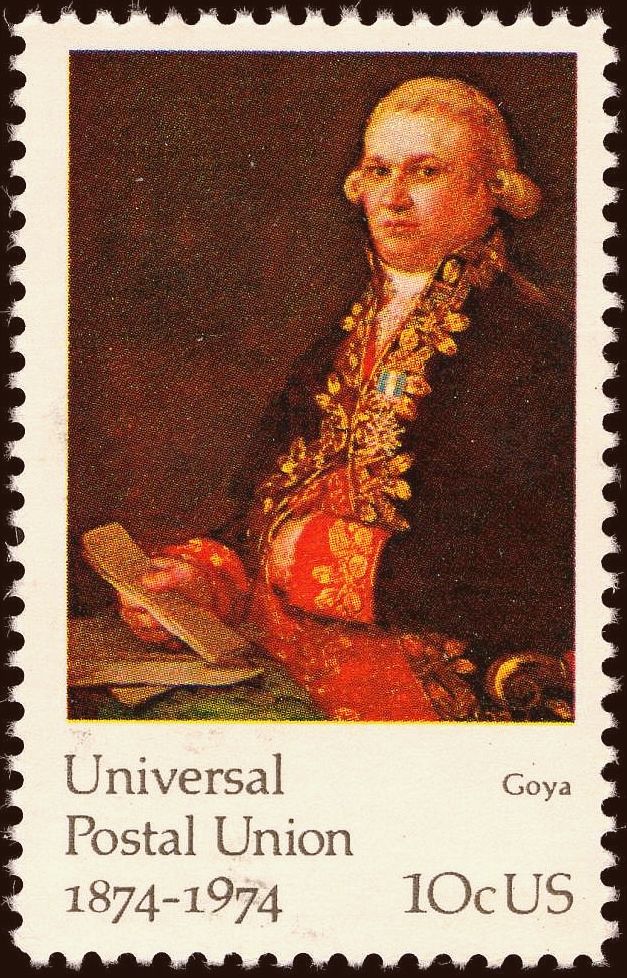

In 1874, a coalition gathered in Bern, Switzerland, to try and take the spirit of Hill’s reforms global. The U.S. and Egypt joined 19 European nations to form the General Postal Union, which implemented a simple fix—all signatory nations would deliver one another’s letter mail from their borders to their final inland destination for free. The assumption (as it turns out, naïve) was that each letter would generate a reply, resulting in an even swap of postal services. Membership in the body exploded, and it was grandly renamed the Universal Postal Union only five years after its founding.

By the early 20 century, that name was almost literally true, and currently 192 of the world’s 196 nations are members—including political outliers like North Korea, but not a handful of Micronesian nations and isolated Andorra. The UPU sets standards for things like labeling and customs processes, and has played a huge if largely unheralded role in the globalization of commerce and culture over the last century and a half. It was eventually absorbed by the United Nations, and is now one of the oldest international organizations in existence.

But observers say it has drifted from its noble roots. Jim Campbell, a founding staffer at the express shipper DHL, is widely acknowledged as the leading outside authority on the UPU—an expertise he calls the “product of a misspent youth.” He is also its most pointed critic, animated by an incredulous disgust with inefficiency that is reminiscent of Hill’s own. To hear the flinty Campbell tell it, while today’s UPU still helps the mail flow, it also facilitates what amounts to price-fixing among national postal services.

The core problem is something known as terminal dues, international transfers which a growing body of research shows are skewing economic motivations worldwide. They arose out of a flaw in the UPU’s founding ideals of equal trade in mail. At the 1906 Rome congress of the UPU, Italian representatives noted that they had delivered 325,000 pieces of printed matter—magazines and newsletters—while sending out none to other countries. This meant they were providing a great deal of postal service to fellow UPU members in exchange for … nothing.

Italy pleaded for a system of compensation, but relief wouldn’t arrive until after World War II, when a wave of liberated colonies entered the UPU. Like other developing nations, they received far more international mail than they sent. Because the UPU’s standards are set through a one-country, one-vote democratic Congress, this influx of net importers led in 1969 to successful implementation of a delivery compensation payment, dubbed terminal dues.

But the terminal dues system quickly created another problem. The initial payment rate was uniform, while variations in currency value, wage costs, and level of service meant that actual postal delivery costs were not. Postal services with lower costs soon received more in terminal dues on inward international mail than it cost them to deliver it. From benefiting net exporters of mail, the UPU had begun to benefit the lowest-cost importers—including both many developing nations and low-cost industrialized nations like the U.S. and the United Kingdom.

The history of the UPU since 1969 has largely been a war of position over who wins and who loses on terminal dues. Ongoing postal liberalization since the 1980s has added another twist—because terminal dues rates were only available to designated national postal services, keeping them low became a way of excluding private couriers like FedEx and DHL from parts of the mail market, including parts where they could have offered big cost savings over national posts. Broadly, this has led to the USPS and its allies in low-cost and developing systems supporting unnaturally low terminal dues, while more internationally competitive and high-cost systems like Germany and Norway advocate a system that recognizes real costs. The low-cost side has generally been successful—sometimes too much so. One draft UPU agreement—known as REIMS—was officially deemed an attempt at price-fixing by the European Commission, and had to be re-drafted.

“This,” Jim Campbell says, “Is a play in which everybody’s a bad guy.”

An ironic twist, though, arrived with the recent explosion of international e-commerce. While terminal dues are nominally for letters, that includes anything up to two kilograms and more or less envelope-shaped. The rise of platforms like Alibaba and eBay has massively increased the volume of small packets being sent by international post directly from developing countries. Things like audio cables, sunglasses, and circuit boards, which had previously been bulk shipped to wholesalers in destination countries, have begun to flow instead through the postal system, directly to buyers—and subject to UPU terminal dues agreements.

Much of that flow is now from or through China, Hong Kong, and Singapore, which, in part thanks to U.S. support in the UPU, pay very low terminal dues on shipping small packets into industrialized countries. This is costing some postal services lots of money. An independent audit found that even the low-cost USPS took losses totaling $79 million on inbound international single-letter post in 2013. Norway Post, a high-cost net importer of mail, has been hit even harder, acknowledging that losses from inbound international mail must be offset by higher rates charged to Norwegians sending either domestic or outbound international mail.

USPS’s losses may be small potatoes when weighed against its strategic priorities in opposing global postal liberalization. But the broader impacts are more insidious. A comprehensive study by the research group Copenhagen Economics has found that the misalignment of terminal dues rates is leading online shoppers to order directly from countries with favorable UPU positions, rather than from suppliers closer to home—even if the price of the item itself is identical. Both USPS and Norway Post’s inbound mail losses have grown steadily since 2010, indicating this trend is accelerating.

UPU administrators have stated that the body is working to make terminal dues more country-specific and cost-based, which would eliminate the current skewed incentives. But rates are set by a political rather than administrative process, and the arcane nature of the issues has generally led home governments to defer to their postmasters’ judgments—and what benefits a nations’ postal service doesn’t necessarily benefit its citizens.

The UPU seems well aware of the resulting resistance to reform. In an internal 1992 brief obtained by Pacific Standard, a UPU team describes the body’s idea of reform as “rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic,” with efforts losing momentum “on the rock of conservative resistance,” and characterizes the organization as “a tomb.”

The U.S. seems to have become briefly aware of this in 1998, when Congress took UPU representation away from a protesting USPS and entrusted it to the State Department. State sent Deputy Assistant Secretary Michael Southwick to the 1999 UPU Congress in Beijing, where he set off a minor firestorm.

Rather than toeing the USPS line in support of low, uniform, and anti-competitive terminal dues, Southwick brought a draft resolution calling for a deeper investigation of the possibility of liberalization, and successfully lobbied for private carriers to attend as observers for the first time. In a characteristic display of UPU insularity, his resolution was tabled for indefinite further study, and private carriers’ representatives were ultimately only allowed into insubstantial plenary sessions.

“These were postal service administrators living in a comfortable world that they didn’t want to change,” says Southwick, looking back on the meeting today. “It just seemed sort of paranoid.”

The outcome of the 1999 Congress, which thanks, in part, to Southwick did yield glimmers of progress, was nonetheless limited. A schedule was set for all countries to transition into a “target” system that accurately reflects costs, with China cued to enter the system in 2016. However, according to Jim Campbell, this transition will have little if any effect, because, while the nominal terminal dues for mailing from less developed to more developed nations will increase, most of that increase will be negated by a cap on payments that remains unchanged. The UPU, then, can point to reform—without actually changing anything.

The upcoming 2016 UPU Congress is the next opportunity for real change—and a crucial one given that the small-packet problem will have five more years to balloon out of control if the status quo is left in place. But Campbell is not optimistic, citing 1999 as a high water mark for reform. He describes UPU congresses over the past decade as reactionary.*

Sir Rowland Hill, lover of freedom and openness, would not have approved.

Lead Image: Postal wagons at the postal sorting facility in Sion, Switzerland. Mail between regional cities is transported by rail, to be delivered by postal bus, vans, and bicycles at a local level. (Photo: Qr189/Wikimedia Commons)

*Update — December 28, 2015: This section has been modified to remove an outside characterization of a former State Department official.