Poverty in the United States is stereotypically associated with racial minorities in urban centers. However, a closer look at social geography reveals a more complex situation: a majority of poor people are white and live in the suburbs. This makes sense when you consider that whites are the largest racial group in the U.S., making up 75 percent of the population, and that there are three times as many suburbanites as there are urbanites.

A majority of Americans are losing wealth, and we know it’s going straight to the top. This is not a conspiracy theory, but the economic arrangement of the last 40 years. The New Deal, which created the middle class and the American Dream, was systematically dismantled by elite interest. The revolving door, the shuffling of elites in top positions of power between the public and private sectors, made this possible. The New Deal was abandoned for neoliberal policy. As a result, the comfortable middle-class lifestyle was replaced by unemployment and working class struggle.

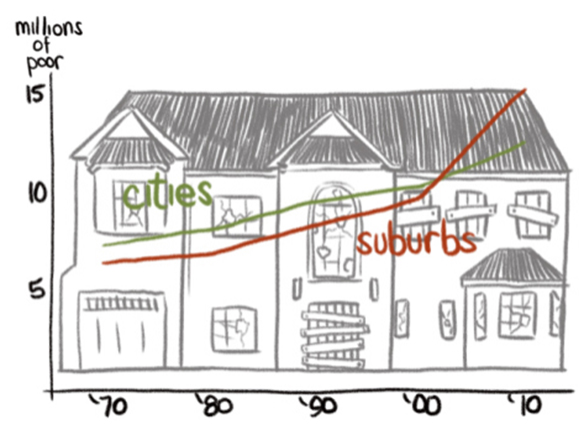

Suburban poverty normally reflects the spread of metropolitan poverty, but in recent years, suburban poverty has been growing at a faster rate. From 2010-2011, poverty in America’s 100 largest metro areas increased by 5.9 percent overall. Suburban poverty grew at a rate of 6.8 percent, while urban poverty grew only 4.7 percent. In general, the poverty rates in urban areas are still higher (21 percent) than those in the suburbs (11 percent). Most notable is the rate of change in the suburbs, which can be attributed to increasing inequality, the housing market crash, gentrification, efforts to make low-income people more mobile, and public housing vouchers.

For the past decade, suburbanites commuted between suburbs rather than into cities for work. More affluent, nearby suburbs provide low-wage service jobs in food and retail. Poverty rates in suburbia are rising due to a crumbling middle class, but the poor are still mainly concentrated in inner-ring suburbs close to cities, and on the fringe—former rural areas consumed by suburban sprawl.

Poverty’s expansion to the suburbs is a symptom of an increasingly unequal society. The geographic isolation of the suburban poor in the inner and outer rings of suburbia troubles the validity of the claim that poverty moved to the suburbs. More accurately, people are getting poorer and more people live in the suburbs—or areas now designated as such. It’s plausible that economic inequality and leapfrog developments have changed the sociogeographic landscape. Low-income earners are displaced to the outskirts of the city (inner-ring of the suburbs) due to gentrification, and the rural poor are now more easily counted among the suburban poor due to suburban sprawl. Whatever the case, suburban poverty presents unique challenges to policymakers because federal antipoverty resources are tailored for densely populated urban areas. The stereotypical images of inner city poverty and suburban affluence are the ultimate fiction.

This post originally appeared onSociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner site.