This year, the federal government has created a public holiday for New Year’s Day on, oddly, January 2. The scheduling quirk is a byproduct of our roaming Gregorian calendar. Every year, New Year’s Day — or any other notable fixed date, from your birthday to Christmas to the Fourth of July — moves forward in the week one day (and two in leap years). Last year, New Year’s Day fell on a Saturday. This year, it’s a Sunday. And no Sunday holiday can come between the American people and a three-day weekend.

There is a kind of democratic virtue in this calendar tic: no one gets a monopoly on annual Friday birthdays. But the ever-changing calendar, with its periodic leap years and mouthful of monthly mnemonic devices, has irked timekeepers almost since the system was introduced in the 1500s.

“It’s a very accurate calendar,” says Richard Conn Henry, a professor of astronomy at Johns Hopkins University. “I must say it does amaze me that it did such a brilliant job of being a truly accurate calendar. It was really wonderful.”

That said, he wants to get rid of the thing. He and Johns Hopkins economist Steve Hanke are now lobbying to replace it with their invention, the Hanke-Henry Permanent Calendar. In the long traditional of calendar reformers, they believe they’ve settled on the elusive solution to the Gregorian calendar’s floating days of the week: one calendar that remains constant every year, where New Year’s Day falls without fail on, say, Sunday every single time.

The big advantage to such a system is that nobody – businesses, the NFL, universities, beleaguered governments — would have to go through the exercise every year of rewriting holiday schedules, course calendars or sports seasons. The Super Bowl would be on the same day every year, as would the start of the academic calendar, Election Day, and the presidential inauguration. Thanksgiving would fall on both a Thursday and a constant date. Christmas could keep December 25 but would get a permanent day of the week as well. (Although holidays based on other calendars, like say Easter, Yom Kippur, Diwali, or Eid ul-Fitr would still bounce around.)

Such a system would also help the economic harmonization of global affairs in an era when business, banking, tourism, and education are all transnational — and would all benefit from a bit more stability in each other’s scheduling quirks. A permanent calendar would also simplify interest payments and other financial calculations. (While they’re at it, Henke and Henry would like to harmonize things even more by abolishing time zones.)

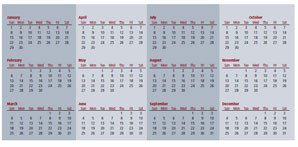

Here’s a look at the Hanke-Henry Permanent Calendar, which gets rid of floating days of the week and leap years while adding an extra week onto the end of December

every five or six years.

The idea actually got some serious traction in the 1950s, when a proposal for a perpetual “World Calendar” came before the United Nations.

“It was a real shame because the whole machinery was in motion, it had the support of a major government body, the U.N. looking at it favorably,” Henry said. “It was just the wrong calendar that was proposed. It was a missed opportunity.”

The length of an actual Earth year is about 365¼ days. In our current calendar, we accommodate for those accumulating fractions of a day with a leap year every four years. The World Calendar proposed instead to insert a kind of off-calendar holiday that, like a pause in time, would be assigned no actual day of the week. The proposal collapsed under the objection of religious groups who hold sacred the seven-day week and Sabbath Day.

Henry’s innovation was the creation of a perpetual calendar that would offend no one’s religious sensibilities.

“It didn’t take me long to realize what the correct answer was,” he said. He inserts, instead, an entire extra week onto the end of December every five or six years. “Knowing my fellow human beings, I expect it would be a party week.”

The rest of the calendar would remain constant with four equal quarters of 91 days each, with two months of 30 days and a third month of 31. Henry first figured this out seven years ago. But the lonely website he created at the time failed to get the word out. And so, more recently, he has brought on board Hanke — also a prolific Cato Institute scholar — to help make the economist’s case for the idea internationally, most recently in the Jakarta-based magazine Globe Asia.

“I’m an astronomer,” Henry said. “I understand galaxies and stars, and the interior of stars and black holes. But I don’t understand fellow human creatures and politics, all of this kind of stuff.”

He’s not quite sure how to turn such a fundamentally jarring idea into worldwide reality.

“That is a deeply interesting question beyond even this silly little calendar thing,” he said. “How does in fact serious change occur?”

It’s happened before, he points out. Peking renamed itself Beijing overnight. During the oil embargo in the 1970s, American highways universally lowered their speed limits on command. (But let’s not recall the United States’ push for the metric system …) And people got used to that. There is even some recent precedent for radical time adjustment. Russian president Dmitri Medvedev abolished two of the country’s 11 time zones last year.

Whatever happens with the Hanke-Henry Permanent Calendar, we’ll know the idea is catching on when we start to hear pushback from the calendar lobby, AKA Big Date. If we used the new system, there would be no need to buy a new and slightly altered calendar every Jan. 1.

Sign up for the free Miller-McCune.com e-newsletter.

“Like” Miller-McCune on Facebook.

Follow Miller-McCune on Twitter.

Add Miller-McCune.com news to your site.