The Great Recession delivered a sharp blow to Americans’ household wealth. Between 2007 and 2009, as the stock market tumbled and housing markets across the country tanked, American households lost 20 percent of their aggregate wealth. African-American families were hit particularly hard by these forces: Between 2007 and 2013, the net worth of the average black family in America fell from $19,200 to $11,000.

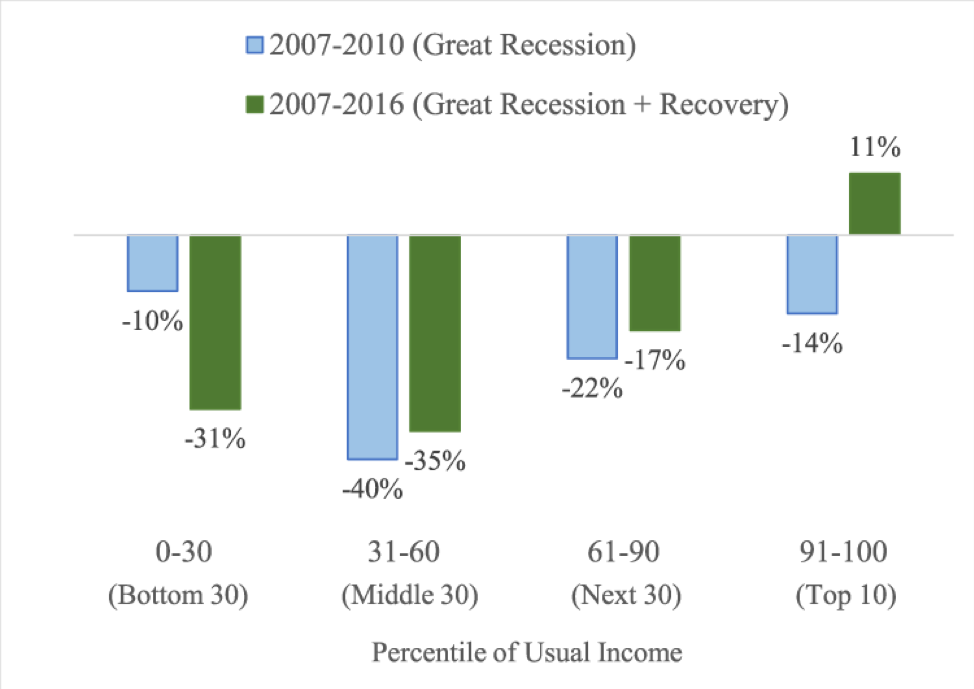

While aggregate American household wealth did eventually bounce back, reaching pre-Recession levels in 2012, this recovery has not been evenly felt by all Americans. In a research note published last month, economists Lisa Dettling, Joanne Hsu, and Elizabeth Llanes of the Federal Reserve look at how the wealth gains of the recovery have been distributed. The chart below, from the report, illustrates changes in household wealth for families across the income distribution in the recession and recovery periods:

“The Bottom 90 and Top 10 alike lost wealth during the Great Recession,” the researchers conclude. “However, the changes in wealth during the cumulative Great Recession and recovery period … illustrate that the Bottom 90 and the Top 10 had vastly different experiences during the recovery. The Bottom 90 experienced little to no wealth gains, whereas the Top 10 experienced outsized gains.”

So why has the experience of the bottom 90 percent of Americans been so different from that of the top 10 percent, both during and after the Recession? The researchers conclude that it all comes down to the composition of wealth. In 2007, before the Great Recession hit, households in the bottom 90 percent of the income distribution held a greater portion of their wealth in the form of housing and stocks than those in the top 10 percent. This made those households particularly vulnerable to declines in the stock market and housing values. Households in the top 10 percent, by contrast, held 61 percent of their wealth in forms other than housing or stock.

Between 2007 and 2016, the percentage of households in roughly the middle of the income distribution that owned a home fell by 12 percentage points, while the proportion that participated in the stock market fell by 6 percentage points. (Home ownership and stock market participation rates for households in the top 10 percent, by contrast, actually ticked up slightly between 2007 and 2016.)

As a result of this retreat from home and stock ownership, households in the bottom 90 percent of the income distribution haven’t benefited from the housing and stock market recoveries to the same extent that the wealthiest Americans have. In fact, the researchers calculate that, if home ownership and stock market participation rates hadn’t changed, “bottom 90 wealth would be 50-60 percent higher in 2016.”

The researchers note that their analysis has big implications for wealth inequality as the economy continues its recovery, writing that “[t]he wealth gaps uncovered in this Note may persist despite the continued economic recovery, as those families will not experience wealth gains from the rise in housing and stock prices since 2016.” A rising tide, in other words, can’t lift households on land.