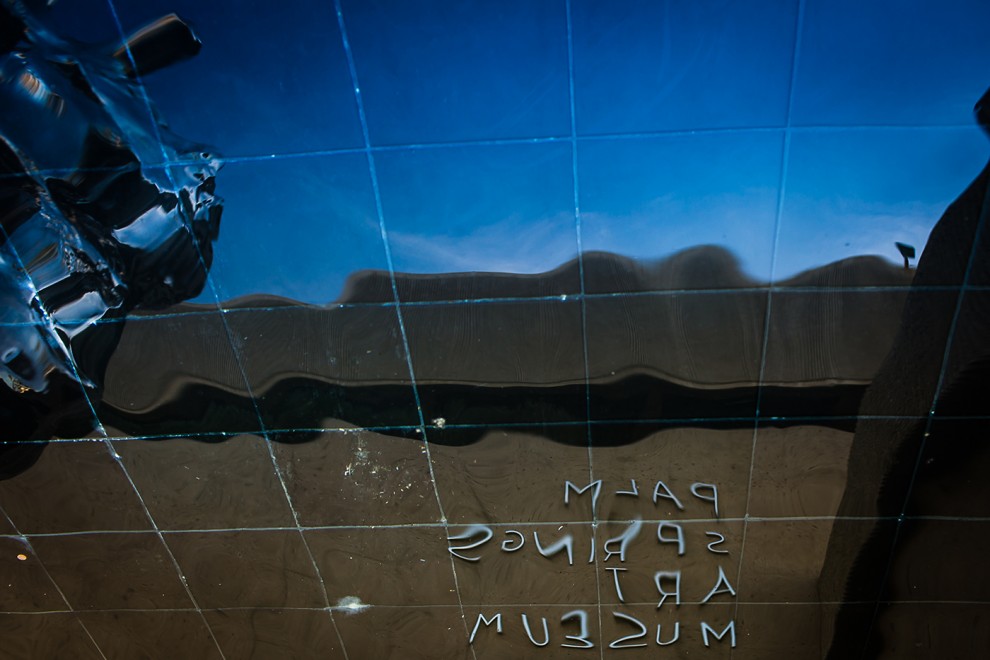

Greg, a tall, handsome septuagenarian in a crisp shirt, a dark brocade waistcoat, a colorful selection of bracelets and beautiful calfskin wingtips, is a frequent volunteer at the Palm Springs Art Museum. As a boy in Downey he studied music with Vance Hayes, who would later teach two of Greg’s friends—the Carpenters. (“You know, they were from Connecticut!” Greg recalls. “They were kind of weird.”) He quit law school as a young man, went on to a long career at the phone company and made successful real estate investments in San Francisco, eventually becoming the owner of a high-rise doorman apartment building there. But then he fell ill and doctors told him he didn’t have much time to live.

“I retired for a reason,” he says. “I have health problems that are forever.” So he went wild, moved to New Orleans and spent a lot of his money. Then came Katrina. “Oh, it was a big thing … oh! Your friends, they didn’t come back, you never saw or heard from them ever again. I had a friend who lived in a boat in the yacht harbor and their boat was gone and they had no place to live … so they lived in my place.”

In time, Greg came back to California. “Twenty years into retirement, I could no longer afford to live in San Francisco! I’d owned the town before and now I was flotsam! I don’t like being like flotsam … you know, that’s not my style.” And like many elegant older people who wind up in reduced circumstances, Greg ended up in Palm Springs. Specifically, in a condo near the golf course at the Desert Princess Country Club.

“Twenty years into retirement, I could no longer afford to live in San Francisco! I’d owned the town before and now I was flotsam! I don’t like being like flotsam … you know, that’s not my style.”

Ed, who also volunteers at the museum, is an old friend of mine. He retired to Palm Springs after a long career in the home furnishings business—a career in which I saw him make a lot of money for other people’s retail and wholesale businesses, including the old Mottura showroom at the Los Angeles. Mart and the Scandinavian firm NotNeutral. Ed is a slightly owlish guy in his sixties, not too tall, with brilliant, deceptively innocent-looking blue eyes and possessed of a disposition equal parts mirthful and sardonic.

The trailer park in which Ed has been living for the last several years is tucked discreetly in between the multi-million-dollar ranch-style palaces of an exclusive Palm Springs neighborhood. Ed’s living situation seems like a metaphor for what has happened to California’s middle class. He’s spent his whole life telling rich people what they should find beautiful—swimming inconspicuously among them and yet not of them. This is what happens when the connection between the value of the work we do and the money that compensates it gets so far out of whack.

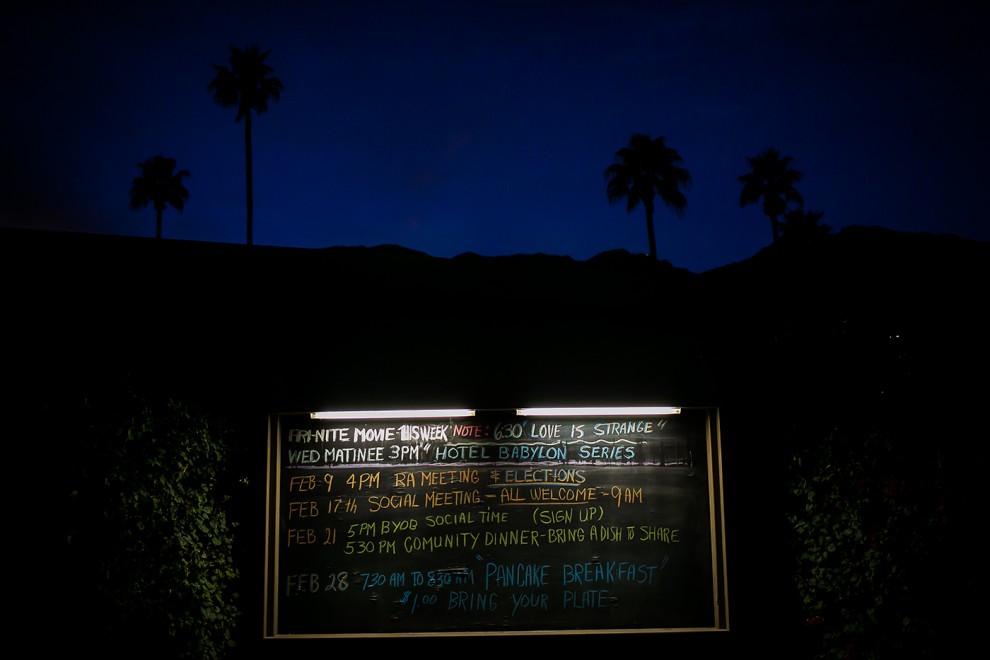

This trailer park, it must be said, is the grooviest one I have ever seen, and Ed’s place is as tasteful and beautifully appointed as any of the many other places I’ve visited him in. There’s a tall vitrine full of art pottery, including the Roseville he’s always collected and loved (though he sold most of his 300-piece collection over the years), and a lovely chintz-covered armchair. Plus there is Dude, the third dog of that name Ed has owned. Dude III is by way of being a local celebrity, having starred as Toto in a recent stage production of The Wizard of Oz.

Ed owns his trailer, which is on Indian land, but pays around $500 per month to lease the land and pay association fees and so on. It has a lovely patio. Even without a lot of money life can be very rich, full and colorful, so it doesn’t appear that Ed is really suffering a lot. Those who have less may also view their own condition as natural, in a way, as a matter of life chances that may not have worked out in their favor. You buy or sell real estate at an inopportune time, a partner or an accountant rips you off, a business you started collapses in a downturn. That’s the way the cookie crumbles, as they used to say.

But then I hear about the other people who helped build other people’s industries but wound up in this trailer park, super-cool as it is: The music director for Henry Mancini; the guy who helped develop Tang; the guy who did the TV sets for Star Trek; the life coach who holds the record for the most appearances on Oprah Winfrey’s show.

News media generally take “inequality” to mean the recent and violent change in the disparity between rich and poor. That is to say: a relative term that refers us to some earlier time “when things were better.” That narrow definition of “inequality” limits our thinking a great deal.

For starters, unfortunately, no human society so far is known to have been fair and just to all its members. If we’re trying to get to that condition—and we shouldn’t lose sight of what chance we have—let’s begin by stipulating that in our reports on the state of inequality in California, we won’t simply take the word “inequality” to mean merely that the rich are richer and the poor poorer than they used to be.

There’s also clear evidence that the rules all across the board, whether in law, business, education, or health care, have grown increasingly skewed in favor of those with the most advantages and against those with the least.

But “inequality” means, too, an inequality of perception: The rich tend to view the disadvantages of the poor as regrettable, but impossible to alter—the incidental result of a natural and just part of the human condition. But what if it isn’t? What if it’s all just the result of greed and blindness, a willingness among those who take and take for themselves to leave everyone else in painfully straitened circumstances?

This post originally appeared on Capital & Main, a Pacific Standard partner site, as “What We Talk About When We Talk About Inequality.” It is part of a month-long series exploring how economic inequality is transforming California, and what can be done to rebuild our vanishing middle class.