Suicide at Foxconn. Poisoned workers. Colluding to inflate the price of e-books. Tax evasion (albeit, legal). Shady suppliers who can’t toe the line of labor or environmental laws in China. Apple’s reputation has taken a hit in recent years. Or, so it seems it should have. But, despite the fact that news reports on the company’s behavior and supplier relationships have been more negative than positive since 2012, Apple’s revenue has continued to climb and break records.

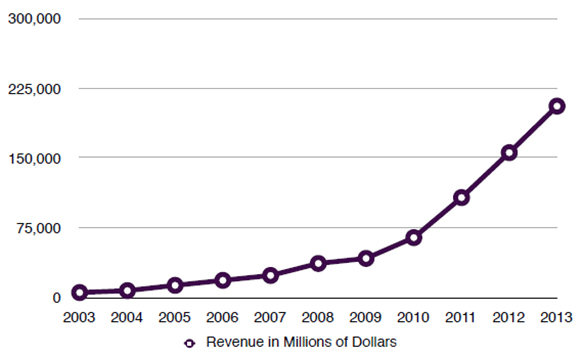

In fact, while the press has illuminated terrible labor conditions in the supply chains for iPhones and iPads (with the most recent revelations coming via China Labor Watch’s report on Pegatron sites where the “cheap iPhone” is in the works), sales of these products in particular have soared, and now account for the majority of the company’s revenue. Apple has jockeyed with ExxonMobil for the world’s most valuable company over the last few years, and currently stands second to the oil giant with $413.9 billion. Remarkably, Apple amassed $156 billion in revenue in 2012 without being the industry leader in any of its product sectors (in terms of unit sales), due to the very high profit margins on iPhones and iPads.

How does Apple maintain this economic dominance in light of negative press that should be bad for its bottom line? How do we, the highly educated consumer base of the company, remain invested in Apple products when work conditions in China and the clever skirting of tax liability grate against our progressive sensibilities? As a sociologist who focuses on consumer culture, I suspect that it is Apple’s brand power that keeps us eating its fruit, and the company afloat. With its iconic logo, sleek aesthetic, and promise of creativity, excitement, and greatness embedded in its products and message, Apple successfully obscures its bad behavior with its powerful brand.

Marketing and branding experts describe a brand as a vision, a vocabulary, a story, and, most importantly, a promise. A brand is infused throughout all facets of a corporation, its products, and services, and is the ethos upon which corporate culture, language, and communication are crafted. A brand connects the corporation to the outside world and the consumer, yet it’s intangible: it exists only in our minds, and results from experiences with ads and products.

To understand Apple’s brand and its significance in our contemporary world, I have embarked on a study of the company’s marketing campaigns. I started with a content analysis of television commercials, and with the help of Gabriela Hybel have analyzed over 200 unique television spots that have aired in the U.S. between 1984 and the present. One of the key findings to emerge is that Apple, and the ad firms it contracts with, are exceptionally talented at what the marketing industry calls emotional branding.

In his book named for this approach, Marc Gobé argues that understanding emotional needs and desires, particularly the desire for emotional fulfillment, is imperative for corporate success in today’s world. After studying Apple commercials, one thing that jumps out about them is their overwhelmingly positive nature. They inspire feelings of happiness and excitement with playful and whimsical depictions of products and their users. This trend can be traced to the early days of the iMac, as seen in this commercial from 1998:

An iPod Nano commercial that aired in 2008 takes a similar approach to combining playful imagery and song:

In a more recent commercial, actor and singer Zooey Deschanel, known for her “quirky” demeanor, performs a playful spin on the utility of Siri, the voice-activated assistant that was introduced with the iPhone 4S in 2011.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GniV1qdFYWgCommercials like these—playful, whimsical, and backed by upbeat music—associate these same feelings with Apple products. They suggest that Apple products are connected to happiness, enjoyment, and a carefree approach to life. To tip the sociological hat to George Ritzer, one could say that these commercials “enchant a disenchanted world.” While Ritzer coined this phrase to refer to sites of consumption like theme parks and shopping malls, I see a similar form of enchantment offered by these ads. They open up a happy, carefree, playful world for us, removed from the troubles of our lives and the implications of our consumer choices.

Importantly, for Apple, the enchanting nature of these ads and the brand image cultivated by them act as a Marxian fetish: they obscure the social and economic relations, and the conditions of production that bring consumer goods to us. Now more than ever, Apple depends on the strength of its brand power to eclipse the mistreatment and exploitation of workers in its supply chain, and the injustice it has done to the American public by skirting the majority of its corporate taxes.

Next: Sentimental Consumerism, the Apple Way.

This post originally appeared onSociological Images, a Pacific Standard partner site.