Over the past 35 years, with the exception of a few golden years in the late 1990s, the wages of low- and middle-income American workers have taken a beating. A new report from the Economic Policy Institute highlights an often-overlooked consequence of this trend: Low-income workers are increasingly reliant on government assistance to get by.

“Arguably the largest economic challenge facing the United States right now is the problem of wage stagnation,” says David Cooper, the report’s author. “For the vast majority of workers, wages have basically barely budged since the late 1970s, and, in the case of low-wage workers, their wages have actually fallen when you adjust for inflation since the late 1970s.”

There’s more than one reason wages in America have stagnated and declined—globalization, economic slowdowns, the decline of unions, the loss of manufacturing jobs—but the government’s failure to maintain the minimum wage at a reasonable level is a major driver of the trend. The federal minimum wage is not tied to inflation, which means that, as the cost of living rises, there’s no automatic mechanism for increasing the minimum wage to account for those rising costs. As a result, the purchasing power of the minimum wage has declined significantly—after adjusting for inflation, a minimum wage worker today makes 25 percent less than a minimum wage worker in 1968.

As Cooper’s report makes clear, it’s not just low-wage workers who have paid the price of this decline in real wages; the working poor are now increasingly reliant on various public assistance programs to supplement their income. In other words, a significant financial burden has shifted from employers to the federal government (and, by extension, U.S. taxpayers). According to Cooper’s analysis, 69 percent of government spending on public assistance benefits for the non-elderly goes to working families (families where at least one member works).

The table below illustrates this trend:

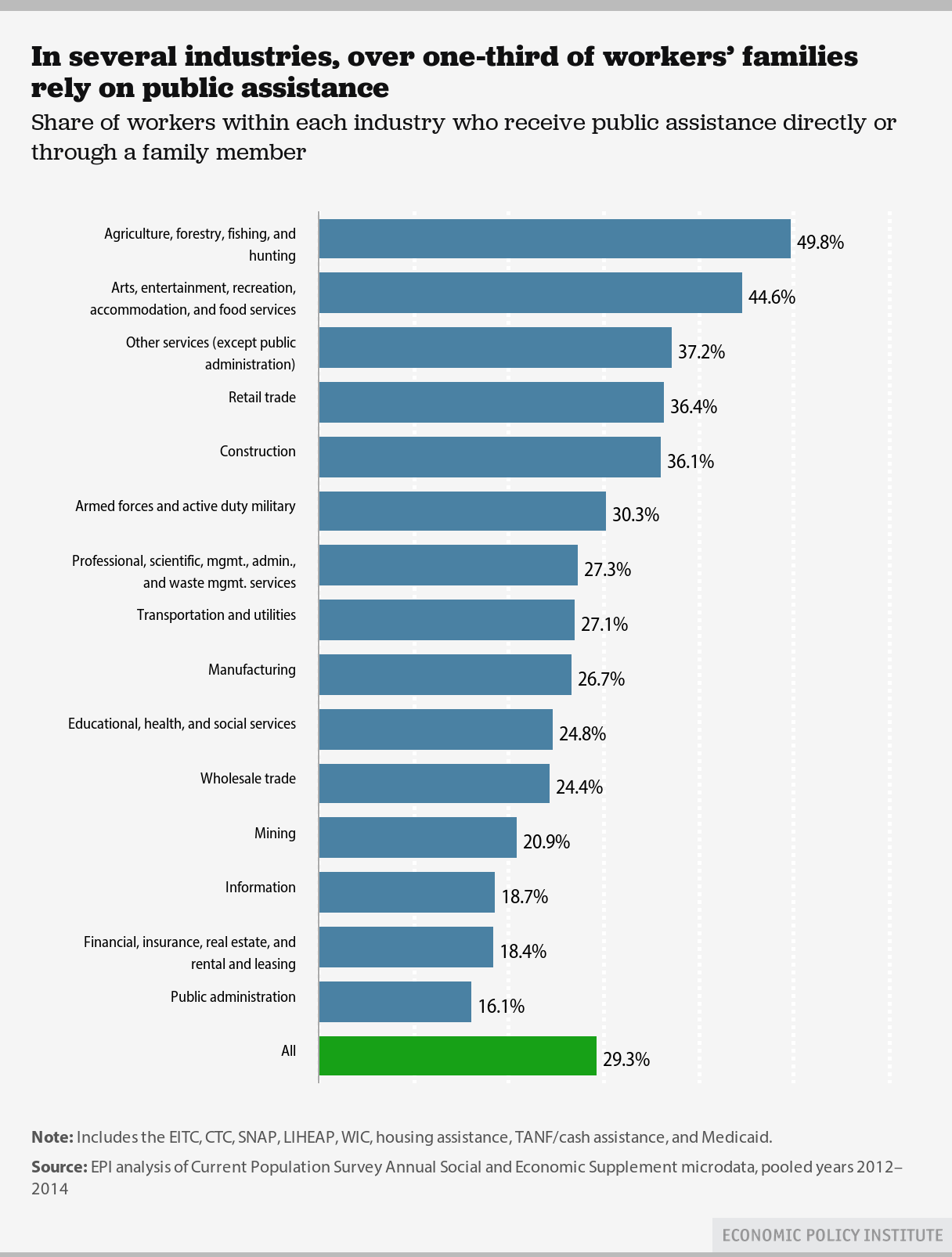

The majority of the working poor receiving public assistance benefits are in the bottom 30 percent of the income distribution, and workers in a few particularly low-paying industries are especially likely to be dependent on public assistance. Almost 50 percent of workers in the agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting industries, for example, receive public assistance (either themselves or indirectly, through a family member). The chart below lays out the share of workers in each industry who receive public assistance:

So what would happen if we attempted to reverse this trend and shift some of the burden back to employers? The Raise the Wage Act of 2015, for example, calls for a gradual increase in the federal minimum wage, to $12 per hour, by 2020. Cooper’s analysis indicates that such a change would reduce the number of American workers who are reliant on public assistance benefits by 2.7 million, while producing $17 billion in annual savings for the federal government. “If we had updated labor standards more regularly, then businesses would already be paying for this,” Cooper says.

While $17 billion isn’t enough money to solve all the woes facing low-income Americans, it’s nothing to laugh at either. It’s enough, for example, to expand the Earned Income Tax Credit to cover childless workers (a proposal with bipartisan support), double housing assistance, triple Temporary Assistance for Needy Families benefits, or fund the president’s universal pre-K proposal.

“You could achieve a lot of policies that are probably going to be put forward in various budgets over the next few months just by raising the minimum wage,” Cooper says. “It seems like a no-brainer.”

Cooper’s estimates don’t include the possible negative effect of a minimum wage hike on unemployment; in theory, increasing the minimum wage might force some businesses to lay off, or hire fewer, minimum-wage workers, which could drive a small share of workers onto public assistance. And as Jared Keller wrote here last month, one major drawback of a nationwide minimum wage policy is that it fails to account for the differences in living standards and economic conditions that exist in different regions across the country. The best available evidence, however, indicates that small gradual increases to the minimum wage have minimal effects on employment.

“The best research has shown that modest increases in the minimum wage—and I would put $12 by 2020 in that category of modest increases—have not had serious negative effects on employment,” Cooper says.

But perhaps more important, in Cooper’s view, is the fact that increasing the wages of low-income workers, either via increases to the minimum wage or other labor market policies, would result in a return to an age in which both employers and the government were responsible for ensuring a minimum standard of living for the working poor.

“The bottom line, though, is that you would be sort of shifting the social contract so that businesses are doing more of their fair share in ensuring that people have a decent quality of life,” Cooper says. “As opposed to continuing to rely on further and further government programs to supplement income for these folks.”