Bong Bai Thao spent her kindergarten year in silence. At school, she didn’t speak at all—not when asked a question by a teacher, not when playing games with other children in the yard. Her teachers, concerned, ordered testing to rule out developmental delays.

Turns out that Thao, the child of Hmong parents who had immigrated from rural Thailand, had endured painful teasing when she first started school in Southern California in the mid-1990s. Her classmates used racial slurs and mocked her accent.

“That teasing stayed with me,” she says as an adult today. “I didn’t want to stand out. I was trying to be invisible.”

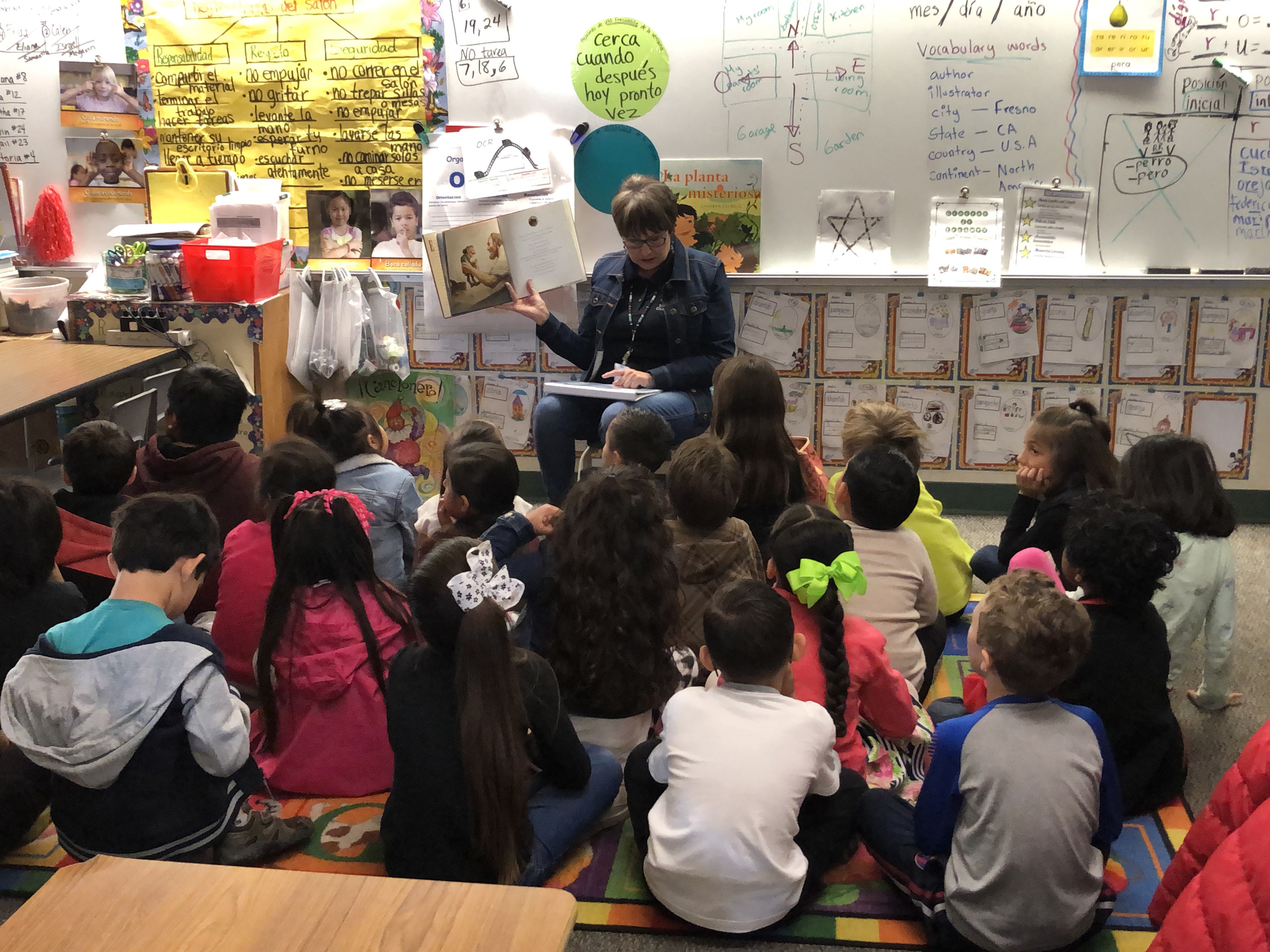

Now a kindergarten teacher herself, overseeing immigrant students who come from families much like her own, Thao does everything in her power to make sure her young students are seen and heard. She is a graduate of the Fresno Unified School District’s Teacher Residency Program, one of several new initiatives designed to help teachers like her create the kind of classroom environment that research shows children from immigrant families need to be successful.

Today, half of school-age children in California are the children of immigrants, many of whom are native-born. Sixty percent of children five and under in the state speak a language other than English at home. And data shows that, unlike Thao, too many of these students do not manage to move past early negative experiences in the state’s public schools. Children classified as “English Learners” fall behind on state testing. And Latino students, who make up around 55 percent of the kids in the state’s public schools today, are the least likely of any group to get a college degree.

“California is the fifth-largest economy in the world,” says Patricia Gandara, professor at the University of California–Los Angeles and co-director of the school’s Civil Rights Project. “We are a huge economy and yet we are putting it all at risk by under-educating this largest portion of our population.”

As Governor Gavin Newsom lavishes attention on, and proposes increased funding for, early care and education programs across the state, observers like Gandara will be watching to see whether the administration demonstrates an adequate understanding of the needs of young immigrant students and their families. Is the state ready to invest in initiatives like those in Fresno? Could Thao’s experience become the norm, instead of the exception?

(Photo: Sarah Jackson)

California set the stage for a new approach to educating children from immigrant families in 2016 with the passage of Proposition 58, which repealed the state’s 20-year-old English-only education law. The old law changed how children learning English as a second language were taught in California’s public schools, mandating that these students be taught only in English and all but eliminating bilingual education programs in most schools.

The 2016 repeal, advocates hoped, would usher in a new era of progressive education for students from immigrant families, one that would finally give students access to strong literacy and language instruction in both English and their home language, and that would allow students to reap the benefits of bilingual proficiency and diversity.

“The celebration that year was amazing,” says Vickie Ramos Harris, associate director of Education Equity and Policy at the Advancement Project California, a civil rights group that advocates for equity in California’s schools. “It was this really interesting spirit of camaraderie and release, to finally have a state policy aligned with what we know is best for kids.”

California has an embattled history of teaching immigrant students. It is a history that includes court fights, as when Chinese-American parents sued the San Francisco Public school system because their children couldn’t comprehend classes taught only in English. This history also includes segregation and remedial tracking—policies that the Chicano student movement protested in the 1960s.

Speak to adults from immigrant families who grew up attending California’s public schools during the 1970s and ’80s, and you’ll hear their stories of being punished for speaking Spanish to their friends at school, of teachers assuming they had cognitive delays, and of their being unable to access the full range of the curriculum because of language barriers.

Educators who lived through the years of the state’s English-only education policies speak about the fear they felt using any Spanish at all in their classrooms, even when they knew it was the way some of their students learned best. Bilingual education was dismissed at the time as a “failed model.” Administrators recall bilingual books being locked away in school basements and their great sadness in having to dismantle bilingual teaching programs that they’d found to be successful.

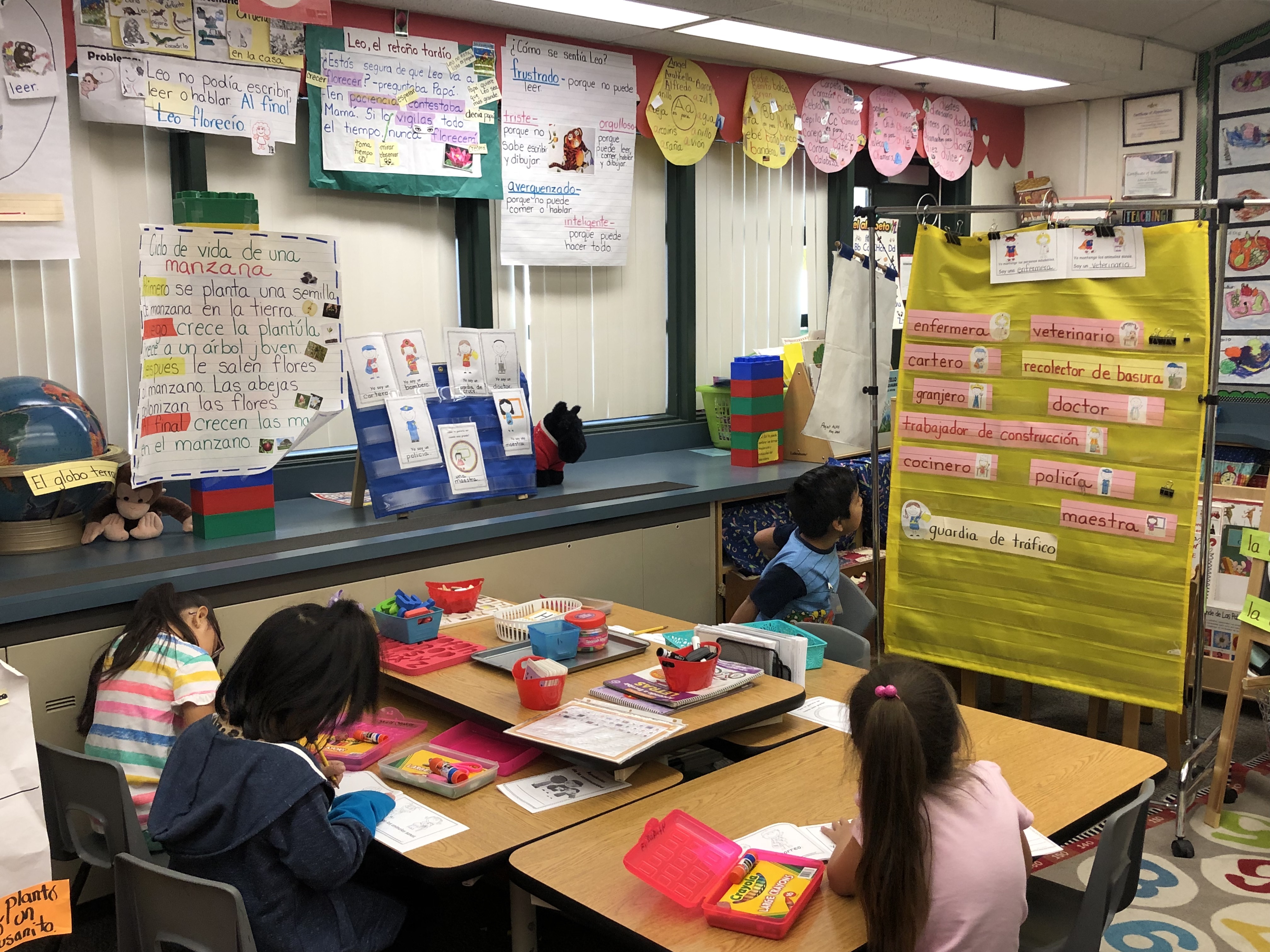

(Photo: Sarah Jackson)

Maria Maldonado, assistant superintendent for English Learner Services in Fresno, remembers those years all too well. Maldonado came to the United States from Mexico at the age of 13 after both her parents died. She came speaking no English. She and her six siblings lived with an uncle in Fresno at first, and then on their own. In middle and high school, Maldonado attended Fresno Public Schools, where teachers told her more than once not to speak Spanish. “You are in America now,” they said.

Today, Maldonado is helping lead the charge to expand bilingual and dual-immersion programs in the district in the wake of Prop 58, and to strengthen instruction for students from immigrant families, who make up at least 50 percent of the students in Fresno Unified. She also leans on a growing base of research showing that development of both home language and English are important for academic success, and on California’s new English Learner Roadmap, a policy released in 2017 designed to enhance the state’s standards for English-language development. Children in Fresno speak upwards of 50 different languages, and 33 percent of kindergarteners in Fresno Unified are dual-language learners, according to the local school district.

“In every one of these students I see myself,” Maldonado says.

The school district has been beefing up its bilingual programs over the past few years, expanding into middle and high schools and opening dual-instruction models at seven new schools this fall, including one with instruction in Hmong, only the second such program in the state. Four years ago, Maldonado started a laboratory program for schools interested in trying out new practices to strengthen language development, which she says is beneficial to all students—not just those whose first language isn’t English.

“Our entire success as a city and as a region is going to depend on how these kids turn out,” says Elizabeth Jonasson Rosas, a Fresno Unified School Board Member. “It is not just one school district, one classroom, one school; it’s how we all contribute to the success of these kids.”

Increasing investments in early childhood—one of Newsom’s favorite issues—is a key part of Fresno Unified’s strategy. The school district began shifting its resources toward students of younger ages in 2011 and has since has attracted increased investment from philanthropic organizations. The David and Lucile Packard Foundation is investing $500,000 a year for 10 years to help ensure that children in the community are well prepared to succeed when they arrive in kindergarten. The money has helped fund new pre-K classrooms and expand transitional kindergarten programs, a new grade level created in California’s public schools in 2010. Overall, these increased investments in early childhood have included work to improve instruction for young dual-language learners in the region.

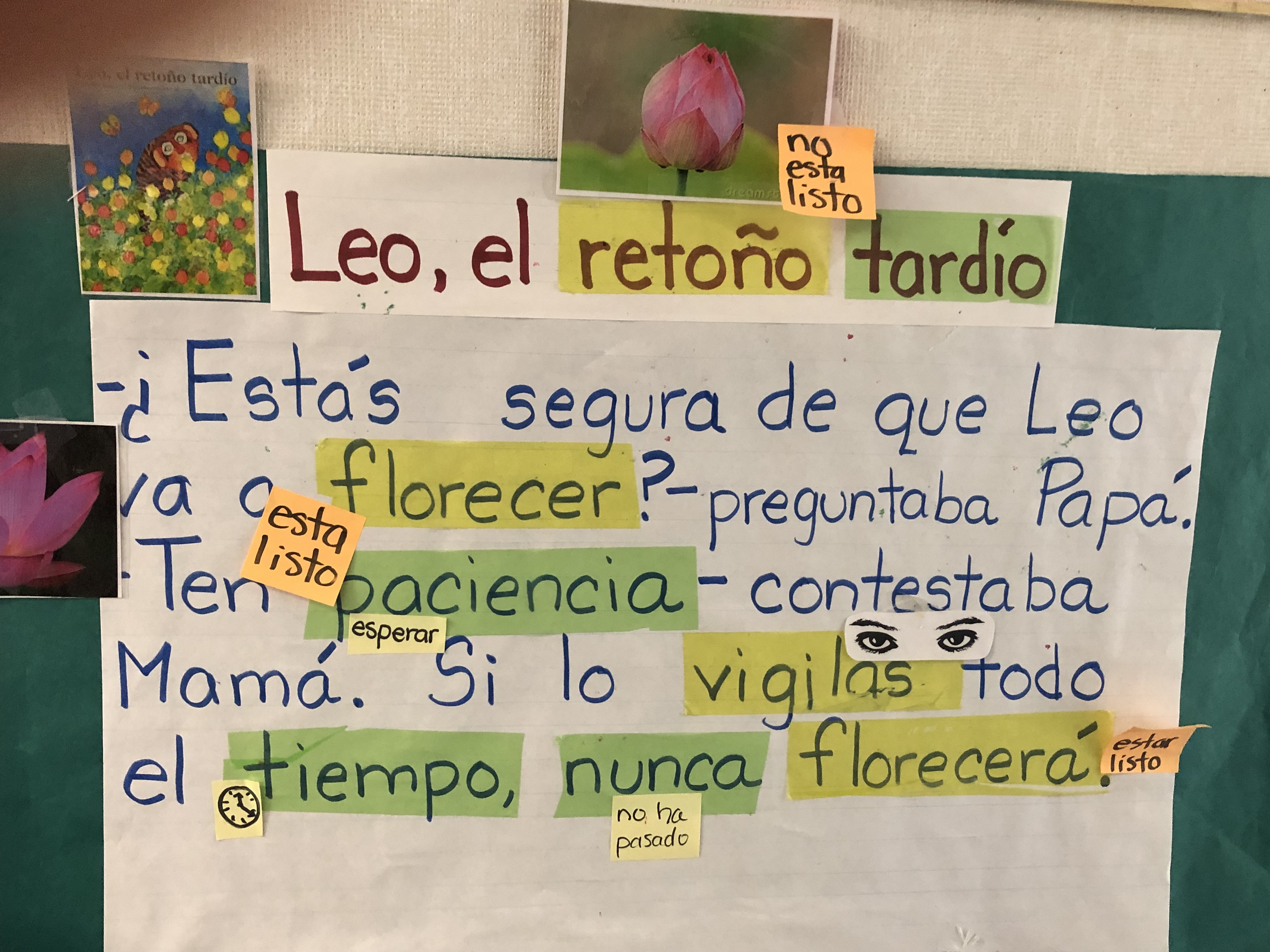

(Photo: Sarah Jackson)

What’s more, Fresno Unified is collaborating on a community-wide training project to strengthen how adults in the city of Fresno work with young children from immigrant families. The collaboration, which has attracted attention (and eventually a grant) from state education officials, brings together adults who work with young children from around the community for a series of collaborative professional development sessions on Saturday mornings. Along with teachers and administrators from the school district, participants include teachers from Head Start, home care providers, and others.

The sessions focus on language instruction, based partly on work by Linda Espinosa, author of Getting It RIGHT for Young Children From Diverse Backgrounds, who advocates strategies to promote oral language development in the classroom. Espinosa’s approach includes a focus on the value of linguistic and cultural diversity, and on family engagement.

Last year, the collaboration received money from the California Department of Education to scale the model in the Central Valley and to conduct its “train the trainer” sessions statewide. The money comes as part of a suite of investments the state has made in training teachers of young dual-language learners.

Last year, California’s (now former) State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Torlakson launched the Global California 2030 initiative, which aims to train bilingual teachers, and to provide more opportunities for students to learn a second or third language at school. The state has also separately invested $5 million for the training of early childhood teachers who work with dual-language learners. First 5 California, a statewide commission that funds programs for children and families, has committed $20 million to improving culturally and linguistically responsive practice in early learning settings through the organization’s Dual-Language Learner pilot. And L.A. Unified, the biggest school district in the state, is piloting dual-language immersion instruction in a group of pre-K classrooms this year.

One looming challenge is finding enough bilingual teachers who are well trained to do this complex work, even with all these new investments. Erica Piedra, the principal of Leavenworth Elementary School in Fresno, says she has trouble finding staff with high-enough levels of academic Spanish to be able to teach in her school’s dual-immersion program.

“It is extremely important to our community,” Piedra says, “that children see teachers who look like them and who share their history, who speak their language and know their culture.”

Yet, as a result of 20 years of almost no bilingual education, few local teachers have the academic Spanish skills needed to teach in the language.

“There is a lot of making up to do now that the demand is so great and the supply of teachers is low,” Patricia Gandara says.

Bong Bai Thao is now in her second year of teaching kindergarten in Fresno Unified and plans to stay. She says her training program’s emphasis on the value of students’ linguistic and cultural diversity has helped her become a better teacher.

“My professors really stressed the importance of getting to know where the kids come from,” she says—to “know their environment, know their community.”

Vickie Ramos Harris, of Advancement Project California, says attitudes in California are shifting. People now, she says, are less likely to ask why bilingual education is important, instead asking, Where do we start?

“And that’s a huge shift,” she says. “That’s a really huge shift.”