This story was produced in collaboration with the Hechinger Report.

There’s a school improvement model that has gotten consistent results in large schools, small schools, high-performing ones, low-performing ones, those with large achievement gaps, diverse schools, homogenous ones, and schools that are rural, urban, and suburban. An impressive track record of hard evidence has made it the only program to earn three levels of competitive grant funding from the federal government since 2010.

But you’ve probably never heard of it.

The Building Assets, Reducing Risks program, known as BARR, was started by a Minneapolis school counselor in 1999, and remained in relative obscurity for a decade. Since 2010, its creator, Angela Jerabek, has sought research support to test the BARR program in other schools. The BARR mantra—”Same Students. Same Teachers. Better Results”—has led Jerabek to aggressively seek out schools in different regions, with different demographics, to test her theory. So far, it holds up.

At large, diverse Hemet High School in urban Southern California, this program helped close the achievement gap between ninth-grade Latino students and their peers within two years. At the mid-sized Noble High School in predominantly white, rural southern Maine, ninth-graders participating in the program were absent half as much as their peers who weren’t exposed to it. At the large, majority-Latino Bryan Adams High School in Dallas, the number of freshmen failing classes dropped from 44 percent to 28 percent in one year.

No matter where a school starts, the BARR model seems to make it better, and it does so without hiring all new teachers, transforming the school curriculum, or spending a lot of money—though it does require a strong commitment in time.

BARR targets students during a make-or-break year: ninth grade. The University of Chicago Consortium on School Research has found that students who earn at least five credits in ninth grade (enough to go on to tenth grade) and get no more than a one-semester failing grade in a core course are 3.5 times more likely to graduate on time.

But these students are hard to reach.

“If you’re going to change kids’ trajectories, the earlier you do it, the easier it is,” says Johannes Bos, a senior vice president at the American Institutes for Research who specializes in randomized control trials in education and has studied the BARR model for the last two years. “You can have nice solid impacts in early childhood programs, or in first-grade programs or as late as third grade, but once you get into ninth grade, it becomes really difficult to change … academic outcomes.”

BARR is able to accomplish so much by prioritizing strong relationships and a focus on student strengths. It forces teachers to track student progress closely and creates a structure for stepping in at the first sign something might be wrong.

“Our system is to catch those coughs before they become pneumonia,” says Justin Barbeau, the technical assistance director at the BARR Center and a former social studies teacher at St. Louis Park High School. “It’s really about giving kids the things they need.”

BARR has eight broad strategies, and, on their own, they sound like plain old, good schooling: Focus on the whole student; prioritize social and emotional learning; provide professional development for teachers, counselors, and administrators; create teams of students; give teachers time to talk about the students on their respective teams; engage families; engage administrators; and meet to discuss the highest-risk students.

Giving a concrete structure to such a holistic focus is what sets BARR apart.

The model requires at least three ninth-grade teachers from core content areas (like English or math) to be on a BARR team. These teachers should have the same students in their classes so they can all bring personal experiences with these kids to their joint conversations. But teachers also split up students and become the main point of contact for a subset of them, which seems to reduce the likelihood anyone will get overlooked.

(Photo: Tara García Mathewson/the Hechinger Report)

The BARR model dictates teachers should meet at least once per week and a larger team of the BARR teachers plus counseling staff should too.

In both meetings, educators work off spreadsheets that identify the students, their grades in all their classes, their strengths, the things they struggle with (in and out of school), specific problems they’re having, achievable goals to get or keep them on track and a running list of solutions teachers have tried. Having access to this comprehensive information is crucial to the model. It creates accountability for educators as they develop and execute plans to intervene with struggling students, and it keeps a running record of a student’s experiences.

Nancy Simard, BARR coordinator and guidance director at Noble High School in Maine, says while team meetings have taken place at Noble since the 1990s, BARR made them more effective. Instead of simply bringing up kids whom teachers happened to be worried about that day, teams track all students, monitoring progress and setbacks for everyone, along with attempts to intervene when students need extra support.

“If you’re just talking about kids in general, it doesn’t give you the structure to have those really pointed conversations about what’s working and what isn’t working for the child,” Simard says. “It really helps us target, not only our interventions, but thinking about student strengths.”

During a BARR meeting with teachers and counselors at St. Louis Park High School just outside Minneapolis this past winter, the team worked through a list of students highlighted on a shared spreadsheet. One had missed a lot of school recently and his grades were low. The team clicked into the school’s learning management system to pull up more information about his attendance, missing assignments and class schedule. A teacher pointed out that he wants to go into the music industry and doesn’t seem to think high school is useful on that path. The team discussed options for working business courses into his schedule, along with more music, and strategized ways to get him more engaged in the rest of his classes. There was general agreement that his grades did not reflect his capacity.

“He has so much ability, but he’s putting in so little effort,” said Sara Peterson, the ninth-grade science teacher.

As they wrapped up their conversation, they filled out a Google form, describing the plan to help keep the student on track, noting his strengths and interests. This automatically populated the spreadsheet and created a record for teachers to review as they followed up with the student and helped change his schedule for the next semester.

These meetings happen weekly, as teams cycle through all the ninth-graders.

When teacher teams run out of ideas for how to help students in trouble, they pass along the challenge to a school “risk review team,” made up of administrators, counseling staff members, and others. This team meets weekly to discuss the highest-need students, struggling with severe mental-health problems, family dysfunction, and serious crises.

The goal in all of these meetings is to discuss students’ strengths and capitalize on them. The various elements of BARR serve as a safety net of sorts. They ensure adults are watching every kid, ready to step in when needed.

The program will expand to more than 100 schools in 15 states this coming academic year (up from 80 last year), and the BARR Center expects to grow to 250 schools by 2020, thanks to money from the federal government to support its scale-up.

John B. King Jr., president and chief executive officer of the Education Trust and former secretary of education in the Obama administration, says what he likes best about BARR, besides its promising early results, is that it “is grounded in the simple idea that relationships matter.”

“The BARR model reflects the conviction that all students can excel regardless of race, zip code, or family income when they are provided with the right supports,” King says.

(Photo: Tara García Mathewson/the Hechinger Report)

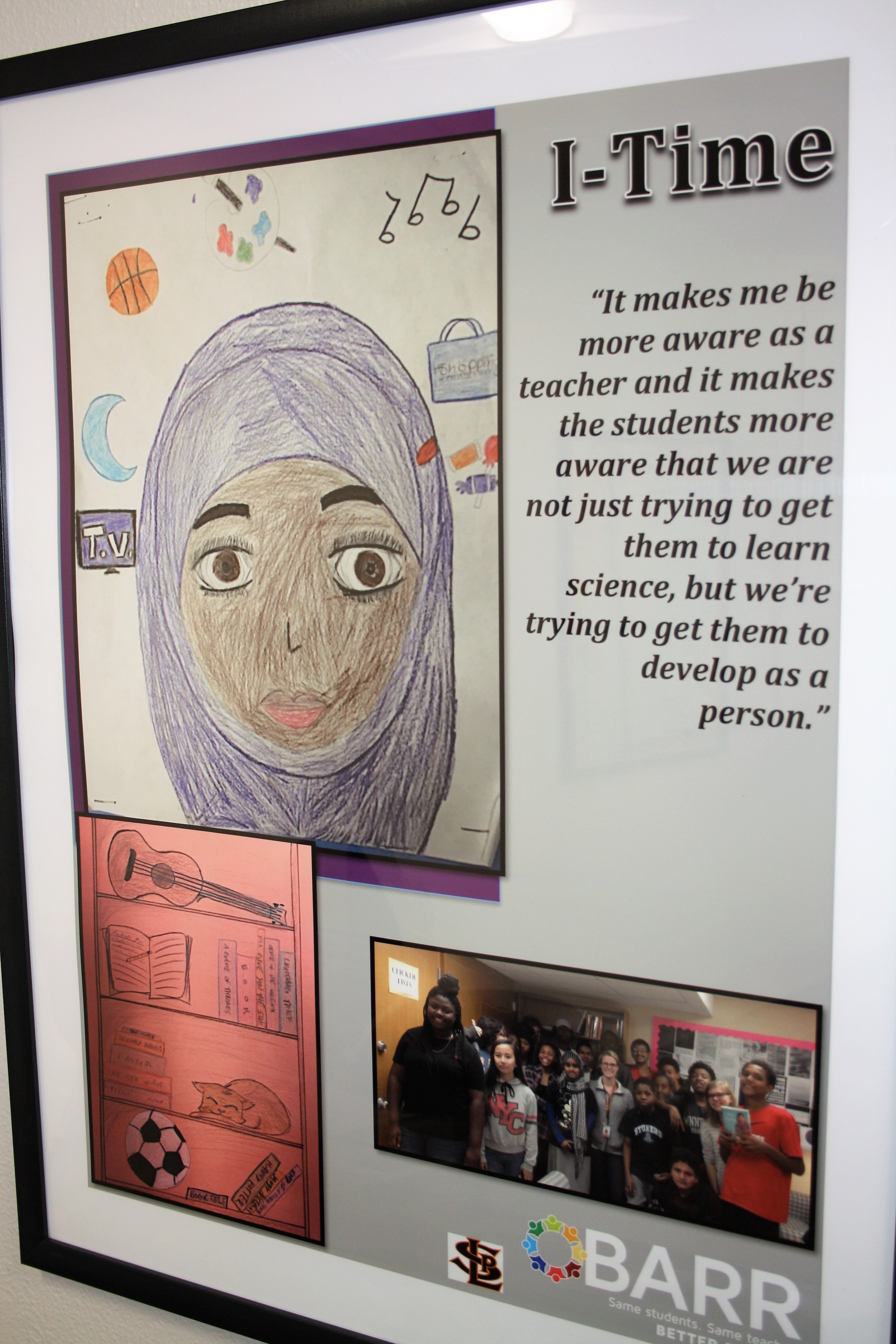

Along with all the behind-the-scenes work performed by teachers, the BARR program features a weekly period for students called “I-Time,” which replaces a portion of one core class. (The “I” in I-Time is for the pronoun, with the period focusing on individuals.) The BARR teachers take turns teaching an I-Time, choosing from a list of lessons concerned with developing students’ social and emotional skills, addressing issues like bullying and substance abuse, and giving students a chance to get to know both their peers and their teachers in a more relaxed, social setting.

Relationships developed in I-Time are meant to increase student engagement in the school community and increase the likelihood kids will show up. Steady attendance means students are present to learn the material that will help them pass classes and do well on tests, two metrics that BARR schools track to consider the program’s success.

Sarah Lindenberg, a ninth-grade social studies teacher at St. Louis Park, started one I-Time class last year with a straw tower construction project. Students were split into small teams and given 40 straws plus two feet of tape. Their task was to construct the largest free-standing tower they could in 15 minutes. The challenge required them to work together, practice design thinking, and move quickly.

“Communication is key,” Lindenberg called out as she walked around the room, monitoring team progress.

Students picked up on the friendly competition, urging their teams on to win. While a handful weren’t particularly active contributors in their groups, most were highly engaged.

I-Time lessons range widely, content-wise, from fun games to serious discussions. At nearby St. Anthony Village High School, a small suburban school just northeast of Minneapolis that is in its third year with BARR, ninth-grader Alice Grooms, 15, says she particularly liked an I-Time that her math teacher led last school year. Students put pieces of paper on their backs and let their peers write notes to them, anonymously. At the end of the activity, students could read through the comments.

(Photo: Tara García Mathewson/the Hechinger Report)

Grooms, whose hair is dyed bright orange, got several notes commending her style and celebrating that she isn’t afraid to be herself.

“People that I didn’t really know were giving me compliments, so that felt really nice,” Grooms recalls now. I-Time offers a chance to get to know peers on a deeper level, she says: “I really like spending time with kids in my class who I see every day but I feel like I don’t know that well.”

Teachers get some of the same benefits from I-Time. They learn more about students that can inform intervention plans and deepen their understanding of why students are behaving in certain ways. I-Time generates great fodder for the “strengths” column on the BARR teachers’ spreadsheets.

Bos, the A.I.R. researcher, says BARR is less intensive than many programs aimed at high schoolers. It doesn’t require a lot of training for teachers—just six days over three years—and schools don’t have to overhaul their curriculum, purchase new products, or hire a number of new staff members.

“Most interventions are definitely more intensive, more expensive, and more invasive,” Bos says. Most also target smaller groups of students, based on some specific risk factor, rather than an entire grade level. And when it comes to impact, focusing intensive services on a small population can garner big results within it. Because BARR focuses on all students, its measured effects can be considered relatively modest. But they’re consistently present, and Bos says BARR is one of the best programs he has studied when it comes to value for the money.

Its power also lies in the universality of its potential impact. In all the different types of schools in which it has been tried, BARR has led to fewer course failures among ninth-graders, higher attendance, better standardized test scores, and reports from both teachers and students that they feel more supported.

Astein Osei, the superintendent of St. Louis Park Public Schools, sees the root of BARR’s success in its focus on positives.

“In education, unfortunately there is a lot of emphasis on deficits,” Osei says. “We’re always trying to figure out how to help students with their deficits. The BARR model flips that on its head.” It asks, he said, what are students good at and how can we connect with them?

And the benefits flow from there.

This story was produced in collaboration with the Hechinger Report, a non-profit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.