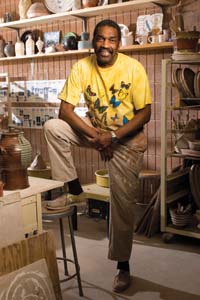

It’s late spring, and Bill Strickland is spending some quiet time in the ceramics studio at the Manchester Craftsmen’s Guild, the art and job-training center he founded in Pittsburgh’s struggling Manchester area. Later in the evening he and his wife, Rose, will host a dinner for friends of the center, followed by the final jazz concert of its season. But right now, he wants to relax and throw a pot.

After wedging and kneading the clay to rid the gray mound of air bubbles, he centers it on the wheel. Centering means more than just proper placement; it is a hands-on process, one in which the right combination of speed, pressure and gentle guidance gives the mound its basic shape. Then, with his forearms pressed gently against his thighs, he makes an initial depression in the clay, and slowly his large hands pull the walls of the vessel out and upward.

Any ceramicist will tell you that centering the clay is critical — if the mound is not centered, a pot pulled from it will quickly be distorted by centrifugal force and then collapse — and Strickland wants it known that he has applied this sense of centeredness to his life, focusing on future possibilities while operating in the here and now. “The trick is to be where you are when you’re there,” he says, “not have your head someplace else.”

It wouldn’t be particularly extraordinary advice — in fact, it would seem dated, a relic of the 1960s — if it were coming from an ordinary 61-year-old at the pottering wheel. But behind his 6-foot-4, gangly frame and shy demeanor, Strickland is far from ordinary: He’s the chief executive officer for the Manchester Craftsmen’s Guild, Bidwell Training Center and the umbrella Manchester Bidwell Corporation, nonprofits with a $12 million operating budget that has grown to support a library, a digital imaging lab, a ceramics studio, a concert hall, a greenhouse, a dining room and a state-of-the-art kitchen where gourmet cooks are trained. In the 40 years since he founded the Manchester Craftsmen’s Guild, Strickland’s been a three-time subject of Harvard Business School case studies, the winner of a MacArthur Foundation “genius” fellowship and a board member for the National Endowment for the Arts. He has lectured at Harvard and met with President Clinton and the Dalai Lama.

Strickland’s recently published memoir, Make the Impossible Possible, describes his life and his basic recipe to enable success: a mix of high standards, the opportunity to develop unexplored talents and the message that no matter how difficult the circumstances, everyone has the potential to live a rich, satisfying life. Strickland’s world-class arts centers and high-level job-training programs have changed the lives of thousands of disadvantaged urban teens, displaced steelworkers and struggling welfare mothers. Now he hopes to foster similar programs around the world.

And what Bill Strickland hopes for, other people often fund. “Bill Strickland could sell anything,” Harvard business professor James Heskett says. “In this case, it’s an antidote to poverty.”

William E. Strickland Jr. has lived in Manchester, a distressed neighborhood of Pittsburgh, his whole life. In the decades before his birth, it was a working-class community, like the British industrial city after which it was named. From steel to railroads to manufacturing, industry prospered along the Ohio River, and Manchester thrived. In those booming early days, merchants and businessmen built stately Victorian homes on inland streets. But by the 1950s, the rush to the suburbs was well under way, and the houses fell into disrepair. The construction of Pennsylvania Route 65 and, in 1961, the Civic Arena (now known as the Mellon Arena) displaced thousands of African-American residents of the lower Hill District of Pittsburgh, many of whom moved into Manchester. Between 1950 and 1990, the Manchester population dropped from 11,000 to only 3,000 or so, and the minority mix shifted, jumping from 17 percent to almost 87 percent African American. By the early 1960s, Strickland was just one of the many failing inner-city kids in Manchester, but he turned out to be a lucky one.

At the beginning of his senior year of high school, Strickland paused by an open classroom door. Inside, a man wearing a hip leather vest sat with his back to the door, but over his shoulder the kid could see a shape that seemed to grow up out of the man’s hands, a lump of clay transformed into a ceramic urn. Bill Strickland was watching a master potter, and the man shaped Strickland’s future as purposefully as he shaped the clay on his wheel. Over the next 20 years, Frank Ross taught Strickland ceramics and exposed him to jazz and architecture and a world full of possibilities.

Ross’ classroom became Strickland’s refuge. As high school neared its end, Strickland planned to be a history teacher. At Ross’ urging, the University of Pittsburgh admitted Strickland, albeit on probation, and he struggled at first; he’d never actually learned to study or take notes. But he graduated in 1969 — cum laude — and by that time had already opened his arts center on Buena Vista Street in Manchester, creating a refuge as much for himself as for others. He could not have imagined, then, that his future would include building a concert hall for jazz where his idols would perform.

When Strickland began speaking in public about his work, his audiences were small and mostly local. On his first trip to Harvard, he carried a beat-up old projector and a slide carousel in a battered cardboard box, its corners held together with duct tape. Today he travels thousands of miles a year to speaking engagements; his audiences are worldwide, his presentations are digital, and he shares the stage with luminaries, including the Dalai Lama, architect Frank Gehry and Alan M. Webber, editor of the Harvard Business Review and founder of Fast Company magazine.

Strickland was invited to speak at California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo in April as part of a series of presentations titled “Provocative Perspectives.” The day of the presentation dawned clear, and a bright sun lit up a breathtaking hillside view from the appropriately named Vista Grande Café. A few minutes after 7, Strickland arrives and has just enough time for the breakfast buffet of huevos rancheros and fruit. Today he’s wearing gray slacks, a blue jacket, a tie with diagonal stripes of light blue and yellow and loafers with tassels, all in keeping with one of his mantras: “You must never look like the problem; always look like the solution.”

Strickland’s presentations are usually autobiographical, and this talk is no exception. He sets the stage by starting at what he considers the beginning, the day a high school art teacher became his mentor and saved his life. He recounts his probationary admission to the University of Pittsburgh and notes, with obvious relish, that he now sits on the university’s Board of Trustees. He is unassuming and makes his accomplishments seem easy to attain. Describing the birth of the Manchester Craftsmen’s Guild, he doesn’t mention obstacles: the falling-down row house that he and his father had to repair themselves or the destruction in the neighborhood that followed the assassination of Martin Luther King. He simply says: “So I built the center in 1968, during the riots. The bishop of the Episcopal Diocese liked me; he gave me an old row house and a couple of bucks, and I started working with kids in the streets. I’m still doing it, only on a much bigger scale.”

In 1972, he also took over the failing Bidwell Training Center; he describes the event with self-deprecating humor and just a dash of pride. “They were looking for some fool to take it over. They said, ‘What about that Bill Strickland up the street? He thinks he’s Moses; he’ll probably take the job,'” Strickland says. “I did think I was Moses, could save all the poor and all that. So I showed up at Bidwell in 1972 — it was in a warehouse with holes in the floor and holes in the roof and the kids running gambling games at the front door. I didn’t recognize the game they were playing, so at the end of the first day I asked the secretary.

“She said, ‘Oh, they were taking bets on how long you’d last.'”

The whole room is laughing, and within moments Strickland has endeared himself to his audience. He’s just a guy, just like them. They are all in the world together, and now he can show them what can be accomplished, invite them to share in the conversation. He knows he’s a pretty good salesman and the sales pitch can’t be just his story; it has to be our story.

As he begins showing pictures of the center, he shares his belief that people find themselves in the process of helping others. He talks of ex-steelworkers and welfare mothers and at-risk kids who never have a nice day in a nice place; in terms of education or job training, they always end up in inferior facilities with marginal teachers. He believed better conditions would bring better results, so he set out to create a facility that was … first class.

The training center’s main building is a 62,000-square-foot, two-story structure of adobe-colored brick, designed by Pittsburgh’s leading modern architect, Tasso Katselas. It has interior curved arches, skylights and works of art — sculptures, quilts, paintings, photos, pottery — seemingly everywhere you look. Even the benches are works of art, oak sculptures handcrafted by Tadao Arimoto. The building stands as an oasis in depressed Manchester, a refuge with a door that opens on a better future. Since its opening in 1986, two buildings have been added: the 70,000-square-foot Harbor Gardens building in 2000 and, in 2003, a 40,000-square-foot, state-of-the-art greenhouse officially called the Drew Mathieson Center for Horticultural and Agricultural Technology.

Strickland’s organization enjoys an unusually high degree of general approval that seems to relate to its relationship with the Manchester community and the organization’s remarkable performance over the past 40 years, as attested by financial and program auditors. In its most recent fiscal year, Manchester Bidwell Corporation vice president of development Ellen L. Woods says, Bidwell and Manchester Craftsmen’s Guild programs served a total of 47,565 people ranging in age from 8 to the mid-50s. Among them were 200 adults from Bidwell’s academic programs for literacy and adult basic education, more than 60 of whom completed their studies and entered a Bidwell vocational training program. Another 100 students enrolled for GED instruction; 25 percent were deemed “GED ready.” Ken Huselton, senior director of operations for Bidwell, says the nonprofit’s 2007 annual report to the Accrediting Commission of Career Schools and Colleges of Technology shows a 75 percent graduation rate and an 84 percent job-placement rate from the vocational programs. On the Manchester Craftsmen’s Guild side, about 500 students between the ages of 13 and 17 attend after-school arts programs each year. Another 4,000 elementary and high school students come into contact with Manchester Craftsmen’s Guild staff through in-school programs and other outreach. The thousands who attend concerts and gallery exhibits during the year are also counted as beneficiaries.

Within an hour, Strickland has covered the scope of Manchester/Bidwell programs and shown the audience dozens of pictures of the buildings, classrooms, library, digital imaging lab, photography lab, ceramics studio, concert hall, greenhouse, dining room and state-of-the-art kitchen. Not to mention the dining hall, where cook-trainees feed students gourmet lunches every day.

The pictures elicit audible murmurs of awe. When he tells the people who are now listening raptly that “environment drives behavior,” they believe him; they’ve seen it with their own eyes. And, as he does in all his presentations, Strickland invites them to visit: “If you’re ever in Pittsburgh, our doors are always open.” Doubting politicians and potential funders have visited, after all, and left with lighter wallets. When he concludes the presentation by suggesting that the time is long past for seminars and sensitivity groups about how to treat one another — that we must get back to common sense and common decency and get on with the job of helping the disadvantaged help themselves — the audience is on board.

Chief operating officer Jesse W. Fife Jr., known as the treasure hunter, has been Strickland’s best friend for almost 40 years, standing by him through his divorce and some heavy drinking days in the 1980s. He’s also godfather to Strickland’s children. Both men were raised on Pittsburgh’s north side and attended the same high school, but they didn’t meet until 1971, when they found themselves as the only two African Americans in a history class at the University of Pittsburgh. After college, Fife worked in sales for Procter & Gamble. He joined up with Strickland to give him a hand with the Manchester Craftsmen’s Guild and the Bidwell Training Center, and they’ve worked in tandem ever since — the salesman and the treasure hunter, the visionary and the implementer. When Strickland has a vision he wants done yesterday, Fife is the one who puts it in perspective, often suggesting a more reasonable timeline but seldom saying, “No.”

At one time, Bidwell training programs received government funds based on enrollment, program-completion and subsequent-employment statistics, but expenses for teachers and overhead remain fairly steady, even when student numbers go down. Just before Christmas of 1995, the center couldn’t make payroll and had to lay off half the staff. The state came to the rescue, and now the center receives a flat amount from the state budget each year, representing approximately 70 percent of the center’s operating budget. Fife and Strickland renegotiate the amount annually, lobbying in Harrisburg alongside state colleges and universities, making it clear that they are servicing a population other schools do not.

Politicians come and go, so to ensure the center’s future, the strictly bipartisan Fife and Strickland keep their eyes open, noting up-and-comers who might be tomorrow’s legislators and other controllers of the purse strings. “The parents like us, the community accepts us; we’re just good PR for politicians,” Fife says. And state funding has opened other coffers. Corporations get educational tax credits; foundations give more easily when they know that a nonprofit’s basic operating costs are covered and they are not being asked to shoulder the whole burden of support.

But that doesn’t mean maintaining support is easy. Heartwarming stories are not enough for funders. Woods, the Manchester/Bidwell development official, knows that the days of funding a concept are gone; she needs statistics and proof, and proving causation is not easy. “The bottom line is that people are benefiting, and the politicians and sponsors get something,” she says. “But that’s not data I can use concretely for a grant.” So the nonprofit is at work on a comprehensive student tracking system, but its most powerful funding tool is still building good relationships.

Marty Ashby, who heads the Manchester Craftsmen’s Guild jazz program, has been on staff for more than 20 years and admits that Strickland’s “no is not an option” determination can put him at odds with funders, politicians and even staff, but his persistence usually wins out. In the early days of Bidwell, those who were resistant to change and did not see things Strickland’s way soon left. Today, the staff of 136 operates much like a family; if there are skeletons in closets, they are well guarded. Strickland’s wife, Rose, describes him as “complex” and says she accepts that his work has a set of burdens that he cannot put aside.

In their small side-by-side offices, Fife works the politics of funding and details of implementation; Strickland focuses on relationships, maintaining those that exist and always seeking out new friends, new alliances, new ideas. He says the keys to uncovering opportunity lie not just in talking about his work but in inviting others to join the conversation and listening — really listening — to what they have to say. Insight, he says, is often observed before it’s understood. He also says he’s just a guy doing his job.

Strickland is driven to succeed, but the goal is not, as he sees it, fame or wealth, even if he has become friends with eBay’s founding president, Jeffrey Skoll, Starbucks’ CEO Howard Schultz and music producer Quincy Jones. He says he never dreamed of becoming a social entrepreneur; he just wants to live his life in a way that makes sense to him. He has decided that building job-training centers, helping people, making pottery, listening to music and raising his family are things that constitute a meaningful life for him. He will also tell you that he’s intense, romantic, creative, entrepreneurial and, above all, patient.

From the day the architect rendered a model of Strickland’s vision, it took four years for the center to be built and open; an additional year passed before the concert hall was added. It took seven years and $3.5 million to build the greenhouse. Sometimes the visions didn’t pan out. In 1993, his nonprofit went into the restaurant business at the then-new Pittsburgh airport. It was one of his early attempts at combining nonprofit training with a for-profit endeavor, and he and Fife were hoping that for-profit components might one day make enough money to endow the school. They quickly learned that small business was not a reliable source of funding, and the airport venture caused a huge financial loss.

Leaving the studio, Strickland expands on his approach while driving his silver Volkswagen Beetle to the greenhouse, with Sarah Vaughan singing softly in the background. The core of any new project or program, he explains, is always education, because an education program provides both the skills and the opportunities that enable poor people — who are unfamiliar with the industry they are being trained to work in — to participate in a life with a brighter future. The students at the greenhouse are learning skills that will land them real jobs in horticulture/agricultural industries, and there is a byproduct: The prize-winning orchids they grow are sold to local florists and Giant Eagle and Whole Foods stores. MCG Jazz has released three DVDs and 32 jazz CDs, four of which won Grammy Awards. These products don’t just generate income and public relations benefits; they engender pride in the students, young and old.

Pittsburgh is not the only city in need of help, and it took eBay’s Skoll to convince Strickland that his model was scalable. They met in 1998, after a Strickland presentation, when a young man introduced himself and shook Strickland’s hand; Strickland, unfamiliar with either Skoll or eBay, pocketed the proffered business card. When his students in Pittsburgh educated him about eBay, Strickland phoned Skoll, and they’ve been friends ever since.

Skoll sits on the board of directors of the National Center for Arts and Technology, the entity he helped Strickland form to oversee efforts to replicate his job-training, education and arts programs around the world. So while his center in Pittsburgh continues to evolve in the hands of his staff, Strickland now devotes more and more of his time to showing others how to achieve similar results.

Nonprofits similar to the Manchester Craftsmen’s Guild and Bidwell Training Center have taken root in Cincinnati, Grand Rapids, Mich., and San Francisco. Although the basic methodology — job training for adults and arts and technology programs for youth — is the same, Strickland preaches that specifics should be suited to the locale: Automotive training in Cincinnati provides workers for the Toyota plant; classes in digital technology are a mainstay in San Francisco; and Pittsburgh is graduating pharmacy technicians, chemical lab technicians and medical transcribers to join the work force at Rite Aid, Bayer, Nova Chemicals and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

During the year or more of planning required to start a Manchester/Bidwell-like facility, the National Center for Arts and Technology helps community leaders with startup tasks, from identifying an executive director, creating a board of directors and designing the facility to constructing a curriculum and developing a fundraising strategy. During the ensuing two to three years, the new center continues to receive NCAT guidance on a wide variety of issues, including the relationship building that has been at the center of Strickland’s success.

The cost of replicating a Manchester/Bidwell facility exceeds $1 million, and once a center opens, the average annual operating budget is roughly $1 million. Plans are in progress to open centers in Columbus, Ohio; Cleveland; Minneapolis; Charlotte, N.C.; and Austin, Texas. But the national scope is not broad enough for Strickland. He is planning a center for Halifax, Nova Scotia, and exploring potential sites in Limerick, Ireland; Kyoto, Japan; São Paulo, Brazil; and San José, Costa Rica. He’s also talking with officials in Mexico, Great Britain and Israel.

Strickland acknowledges that the fatigue from constant travel — and the sheer magnitude of the task at hand — gets him down sometimes. There have been times when he’s wished someone would give him permission to stop trying to sell the notion that poverty has an antidote. For whatever reasons, he always winds up getting excited about change and the next important connection he might make. Georgina Gutierrez, NCAT’s director of replication, who will help Strickland try to create 200 centers worldwide in the next 15 years, sees the goal as reasonable, given the person chasing it. “He’s a special man, with vision, humility and heart,” she says. “There’s a hurry in his spirit.”

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Click here to become our fan.