Far away, in a realm of pasty white men located somewhere between traditional video games and viral marketing campaigns, there is a strange category known as Alternate Reality Games (ARGs). They are staggeringly complex, but if you remember what happened to Michael Douglas in The Game, you have some sense of how they work. Instead of a PlayStation or a mobile phone, an ARG’s platform is the physical world. Incorporating elements of scavenger hunts, board games, role-playing games, hacking, performance art, and science fiction—among other influences—ARGs are amorphous, experimental, and seemingly endless, often lasting for months at a time.

Most ARGs are used as marketing tools with the goal of forming a fervent community around a separate, but related, product. Three examples are The Beast, which was tied to A.I.: Artificial Intelligence; I Love Bees, a viral marketing campaign for Halo 2; and Year Zero, which accompanied the eponymous Nine Inch Nails album. As you might infer from that list, ARGs tend to cater to a white male demographic. But the Game Changer Chicago (GCC) Design Lab, a new initiative at University of Chicago, specializes in creating games geared toward an unusual audience: African-American youth.

GCC was founded by Melissa Gilliam, an OBGYN frustrated by the health care disparities in Chicago, and Patrick Jagoda, an English professor who specializes in games and new media. The two met shortly after Jagoda came to U. of C. a few years ago. “We started having extremely robust conversation, and it was rich in part because we’re coming from such different places,” he says. “We spent a great deal of time translating our message and our investments to one another, and came to this idea that neither one of us would have come to alone.” Together, they direct several full-time game developers, student fellows, and sundry collaborators to create multimedia games that promote social justice, emotional health, and sexual education.

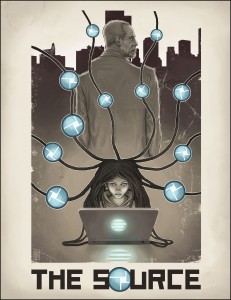

While ARGs have never taken off as a consumer category (probably because the games are difficult to develop and monetize), they’re fertile ground for researchers at places like GCC, which is funded by the university and grants from organizations like the MacArthur Foundation. Last summer, GCC embarked on its most ambitious project to date, an ARG called The Source. Over five weeks, 140 high school students competed in teams of 10, with the game unfolding on the University of Chicago’s campus and a few partner sites across Chicago.

Like other ARGs, The Source combined a series of discreet games and tasks with an overarching narrative. (Unlike most ARGs, it was administered through a day camp-style program that subsidized participants’ meals and bus passes.) The heart of the narrative is a series of 15 webisodes in which the game’s protagonist, a 17-year-old African American named Adia, finds a letter from her father, who disappeared when she was five.

The letter outlines an elaborate game her father designed to stand in for all those missed years. His goal is to teach her about life, but Adia’s goal is a little different: She believes the game will reveal her father’s whereabouts. The catch is she can’t do it alone; she needs your help.

Uninhibited by the teach-to-the-test mentality that plagues public school curricula, GCC used The Source to pursue ambitious educational goals. Instead of focusing on facts and figures, activities were designed to teach skill sets and create a safe space for talking about social justice issues that impact the lives of participants, many of whom reside on the South Side of Chicago. The five weeks were organized around broad themes. Since Adia’s father is an engineer, Week One’s activities related to engineering and urban planning. Week Two explored sexual health through the perspectives of hard science, psychology, sociology, and political activism. Week Three delved into math via cryptography, letting kids play detective and crack codes. Weeks Four and Five focused on technology and art, respectively. Across the five weeks, there were board game sessions, workshops that bolstered digital literacy skills, visits from experts and community members, scavenger hunts at sites like the Museum of Science and Industry, and field trips to places like the Art Institute.

While most of the narrative was propelled by the webisodes, The Source’s characters also communicated directly with participants in real time. “Adia” had a live cell phone that she used to send text messages and voicemails to the teams, and many of the characters posted on blogs and on Facebook. A few other tools, including Adia’s father’s purposefully dated-looking website, were used to layer in elements of authenticity to encourage players to feel vested in the game.

These elaborate efforts worked—perhaps too well. Jagoda and his colleagues had hoped the participants would suspend disbelief, but some kids began to suspect (or even fully believe) the game was real.

“I was walking down the hall at one point, and I overheard two players talking,” says Jagoda. “They were looking at a text and saying, ‘Wait a second. Is Adia real?’ That .01 percent chance that it’s not a fiction is all you need. You don’t need a 50 percent chance. There’s something magical about that seed of uncertainty.”

In a blog post about his turn as a guest speaker during Week Three, cryptologist Daniel Weinstein marveled at the way in which some of the students perceived the game. “At first I was a bit incredulous that any of the youths actually believed the story of Adia was true,” he writes. “However, when I was introduced to the students as Abe’s [Adia’s father] former pupil, I realized this story was perceived by many of the players as genuine.” Further, Weinstein felt that the players’ belief motivated and enhanced their learning:

I was again surprised to find the narrative of Adia and Abe provided the youth extra incentive to master their ciphers. Teaching cryptography to youth can be a difficult task since only easily breakable cipher can be mastered by teenaged students. … I appreciated the approach The Source took to cryptography by removing classroom type lectures on ciphers and instead letting students struggle through ciphers mostly on their own. This approach would have been risky if students didn’t have a vested interest in the decrypted message because breaking a cipher is an exercise in perseverance. I got the distinct impression that the students really cared about Adia reconnecting with her father and that drove many of the groups forward.

The line between the game and real life blurred even more when one team “found” Adia’s father, a random man in Missouri, and sent him a Facebook message. On the developers’ blog, GCC fellow Philip Ehrenberg interpreted the participants’ mistake as a sure sign that he and his team were doing something right:

Rather than viewing moments like this as a hitch in our master plan, we run with it, incorporate it into our narrative, push against the players while encouraging them to continue…. We also celebrated. One intrepid team of players had taken our various puzzle pieces, questioned the assembled narrative, and done their own research. … It means the players have accepted our invitation to engage in a more pervasive type of play.

The incident sounds harmless enough, but it’s easy to imagine how, under different circumstances, it could have turned into a more serious invasion of privacy. What if the man had lived in Chicago instead of St. Louis and students had gone to his home? Or what if it had been a different character—say, the minor who had a sexually transmitted infection?

Cheating Week

We’re telling stories about cheating all week long.

The character of Adia’s father becomes problematic in other ways when the story is taken literally. It’s not that he’s idealized; over the course of the game, he is described as homophobic and mentally ill, and there is no fairytale ending. Still, as the author of this elaborate game, he has a magical omnipotent quality despite his physical absence. While the “magical missing parent” is a fairly common device in young adult literature, it’s typically employed in worlds that are clearly marked as not only fictive, but fantastical, like the Harry Potter series and the His Dark Materials trilogy. The Source, on the other hand, was designed with what Jagoda describes as an “urban realist aesthetic.” The world of the game—its look and feel, its characters, and the narrative itself—was purposefully engineered to resonate with the real-life experiences of its players, and it worked so well that some players failed to understand that the protagonist was a character played by an actress. In this context, is it irresponsible to romanticize the story of a missing dad to kids who might have plain old absentee dads (or moms) in real life? Or is it sort of beautiful to make room for magic and mystery in an experience that is, for many young people, difficult and sad?

These questions don’t have easy answers. But their premise—that the game’s success can be attributed, at least in part, to the way in which it blurred the boundaries between the game and real life—perhaps underestimates the power of fiction. While The Source is clearly the product of creative minds, the assumption that kids would somehow feel less vested in a story blatantly labeled as fiction is a fundamental failure of imagination. Obviously, fiction isn’t technically true. But as anyone who has been moved by a novel (or a film, or whatever) can attest, made-up stories have plenty of potential to teach and engage—and maybe even change a life.