What’s so great about being a customer? Every time Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos—or really anyone in the Republican Party—talks about higher education lately, they talk about choice and tout the student as customer. Is being a customer so great if you’re not a billionaire?

“The customer is always right,” goes the saying. It’s one of those phrases so embedded in our culture that we rarely reflect on its fundamental untruth in a world of constrained choices. I was thinking about it recently, as I sat in an airport terminal choosing between spending money I didn’t have or sitting in middle seats in the back of a Delta plane. I was a customer. I had choices, but they were false choices, constrained by capitalist systems and lack of personal wealth. At literally the same moment, a notification popped up: DeVos had just written a new op-ed for the Wall Street Journal defending stripping away choices from students on the grounds that students are “customers.”

DeVos’ op-ed is about students loans. The Obama administration made many attempts to build a better loan system given the constraints of the need for private funding (since free college ideas went nowhere in Congress). An unwieldy array of instruments through multiple private partners emerged to handle the massive debt load of America’s current and former students, with some adequate results and improving flexibility. In some ways, it was a classic achievement by President Barack Obama: complex systems, bad optics, but reasonable gains given the constraints of Washington gridlock. In the op-ed, DeVos defended reverting to the Bush-era model of servicing student loans. Instead of multiple corporations vying for contracts, with an array of diverse financial instruments intended to make repayment more manageable, a single company will oversee everything. DeVos concludes her op-ed by writing: “This is another example of President Trump’s commitment to put students first, improve the functionality of government, and protect taxpayers. Students will now be treated as valued customers and afforded the protections and respect they deserve.”

The wrong framing and financial models can turn education into an engine for inequality.

There are two big problems here. First, the student-faculty relationship cannot be reduced to a simple capitalist transaction. To do so demeans the students and misconstrues how learning works. Second, being treated like a customer is often extractive. From the correspondence school frauds of the Roaring ’20s to the worst excesses of today’s for-profit industry, the history of American higher education is full of people who promised “customer service” while milking students for every buck they could get. I’m worried the Trump administration will encourage unscrupulous lenders and institutions to view students as sources of revenue, not partners in education.

Let’s start with the basics. Plenty of transactions take place in the context of higher education, but education itself is not a consumable good. Students pay for well-organized and appropriately structured opportunities to learn. To call them “customers” diminishes (impoverishes, even) the nature of the interactions between faculty, staff, administration, and students. We join in a collaborative and reciprocal enterprise that should have long-term rewards for students, including a good career but also a set of fundamental values and the ability to grow as a life-long learner. Money changes hands, although that’s not the only possible model for funding education, as high-quality examples from around the world demonstrate. German universities remain free or extremely cheap for students and are excellent, as more and more American students are finding. The best American universities are non-profit for a reason.

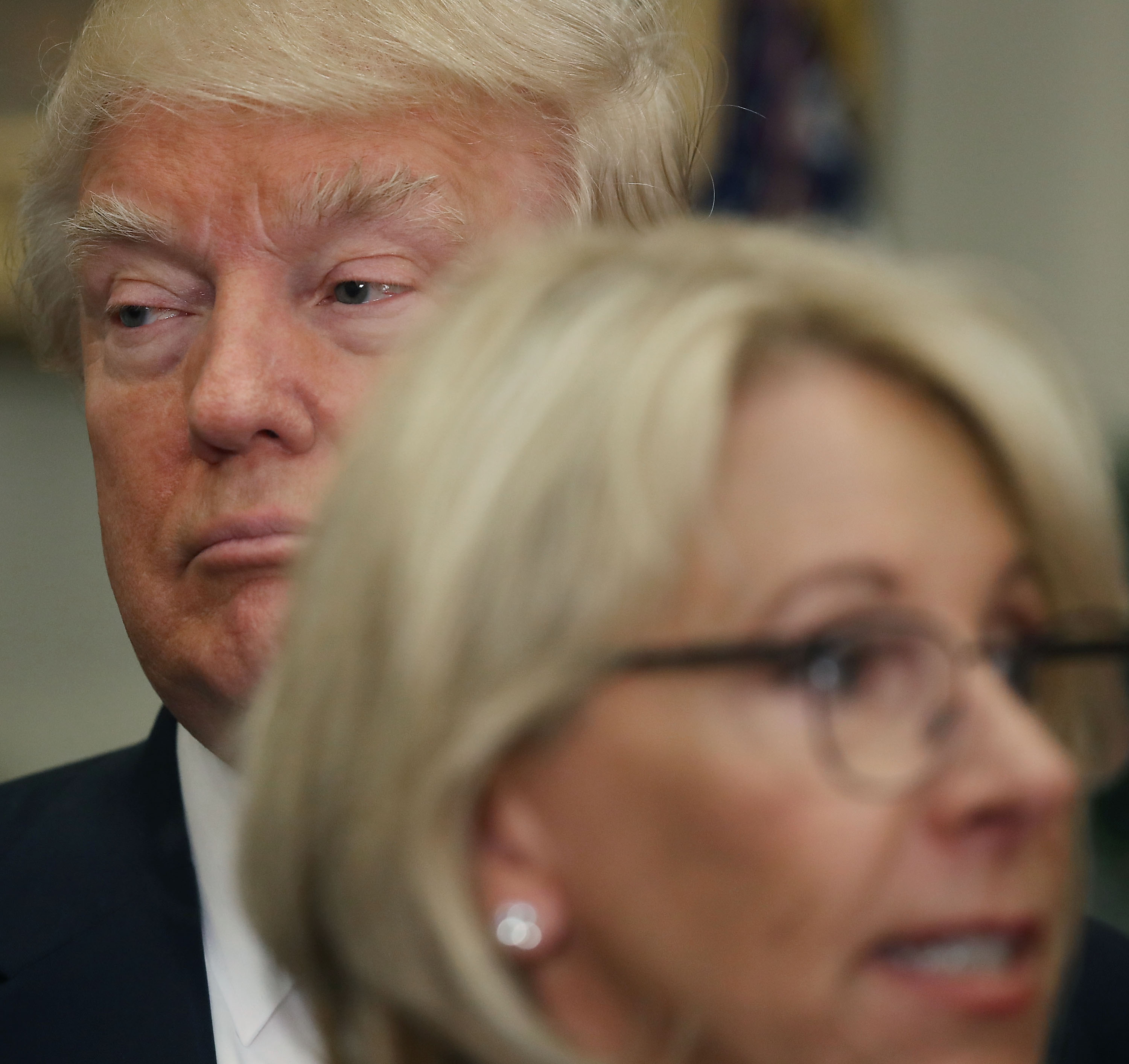

(Photo: Mark Wilson/Getty Images)

When students constantly hear the “customer” rhetoric, moreover, there’s reason to think their attitudes toward higher education shifts, and not for the better. I’ve long understood the rise in certain kinds of student behavior as linked to the corporatization of the university. When we tell them they are customers, they take on the attitude that a university is selling them a credential with a financial pay-off, rather than an opportunity for them to work, learn, and grow. No wonder there’s a wide perception (without, to my knowledge, evidence) among faculty that “students these days” are more entitled and less willing to work. The “customer” rhetoric sets up a clash between university employees and students, rather than joining us together in common purpose.

Perhaps more important than the rhetorical and cultural problems of “customer” rhetoric in higher education, we have really good evidence for what happens when schools genuinely embrace the “customer” model: the American for-profit university. In one of the most important books on higher education of the year, Lower Ed: The Troubling Rise of For-Profit Colleges in the New Economy, sociologist Tressie McMillan Cottom details the rise of institutions designed to turn “inequality into profit even when we, citizens and persons, would agree that it is immoral for them to do so.” The book combines meticulous data-driven research into the outcomes of students who have gone into the for-profit world with often painfully vivid anecdotes of individual lives shaped by such profiteering. McMillan Cottom’s analysis is inclusive and expansive, linking the specific for-profit world to “credential expansion created by structural changes in how we work.” The connected series of social structures, values, and institutions that the author collects under the neologism “Lower Ed,” she argues, “can exist precisely because elite Higher Ed does.” Americans work differently now, and those labor changes have created more inequality, penalizing especially “women, minorities, and minority women.” Throughout the book, moreover, McMillan Cottom argues that education inequalities are in part due to the way we talk about education: narratives about credentials and career outcomes, “just stay in school,” and, ultimately, the whole concept of the American Dream. I’d add the billionaire secretary of education saying words like “choice” and “customer” to that list.

Education can be an engine of social change, a vehicle toward equality. McMillan Cottom makes it clear, though, that the wrong framing, policies, and financial models can turn education into an engine for inequality. To me, DeVos’ false insistence on “choice” and on students as “customers” drives us toward the latter outcome. As a billionaire, she’s going to fly in a private plane or at least in first class. As a white, cis-male, middle class professor and writer, I get a cramped middle seat in the back. More vulnerable Americans, meanwhile, will be left behind entirely on the ground.