That there are fewer women than men in the “hard” sciences is a phenomenon long known but little understood. According to various reports from the U.S. government, about a quarter of all the jobs in the fields collectively known as STEM—for science, technology, engineering, and math—are filled by women, who comprise just under half of the American workforce as a whole. That figure actually reflects an improving picture: Between 1993 and 2008 the share of women working in science or engineering rose from 21 percent of the total to 26 percent, according to the National Science Foundation. And even in the sciences, women are more likely to be in the social and biological sciences (including medicine) than in engineering, math, or computers.

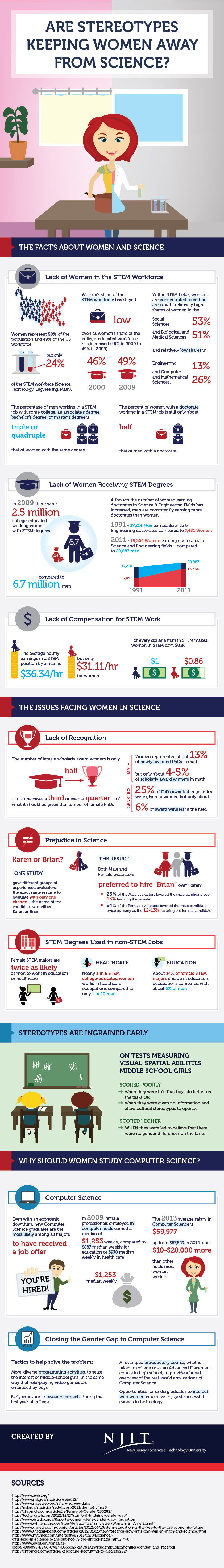

There are lots of reasons posited for this discrepancy–lack of female role models, job demands that aren’t family friendly, or self-imposed stereotypes. The last, as the graphic from the New Jersey Institute of Technology below shows, is one of the most commonly cited reasons for the difference.

In 26 published studies drawn on test results from 12 different universities, “male students almost always outperform female students” both at the start of the course and when it’s over.

But in a data-rich environment like physics, the numbers tell another story. A new meta-analysis in Physical Review Special Topics – Physics Education Research examines why women routinely score lower in physics assessment tests. The multiple-choice tests, known as “concept inventories,” are used to see how well students get the underlying material, and have been a godsend in improving instruction and pushing teachers to be more interactive and less didactic.

In 26 published studies drawn on test results from 12 different universities in the U.S. and Britain, “male students almost always outperform female students” both at the start of the course and when it’s over, the authors write. The difference in scores—12 percent on average for tests about force and motion, with a smaller difference from tests about electromagnetism—showed up across institutions and across teaching methodologies. The difference varies across time and place, but this gender gap never goes away. (Only one instance of women outscoring men showed up, in an electromagnetism assessment at the University of Colorado-Boulder.)

The authors—Adrian Madsen, Sarah B. “Sam” McKagan, and Eleanor C. Sayre, all female and all deeply involved in physics education—set out to find out why. After grappling at length with the issue, they found that the reason is, well, not obvious.

“We haven’t found a miracle that solves the gender gap,” McKagan was quoted in a release from the American Physical Society. This non-discovery wasn’t from a lack of trying. Reviewing the gender gap studies, the trio identified 30 different factors that have been used to explain the differences. They then boiled those down to six families of factors, including differences in background and preparation, gender gaps that appear on other measures, answering questions based on their personal beliefs rather than what they think a “scientist” would answer, effects from teaching methods, so-called “stereotype threat,” and how question wording affects answers. Some of the source studies in the meta-analysis were quite strident in identifying a key issue, but then other work contradicted that finding.

With the exception of stereotype threat’s effect on performance—which got a big maybe here and a big probably elsewhere—none of these families of factors could fully or even largely explain the disparity. Stereotype threat does affect women’s performance in other arenas—being asked to report their gender has been shown to lower girl’s scores on advanced placement calculus tests, for example, and women reminded that women are allegedly poor drivers were then more likely to hit jaywalkers in a driving simulation. (The paper is available for free and for an academic opus it’s accessibly written, so take a look at the deeper analysis on these issues here.)

One possibility the authors didn’t raise is that there might be some sort of inherent biological difference between genders. While it would take a brave person—or perhaps a foolhardy one—to even suggest this, a glance at global science aptitude courtesy of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development suggests that culture, not genes, are at play. Examining 15-year-olds in 65 developed countries, girls outscored boys in the majority. Boys, however, outscored girls in Western European nations, the United States, Canada, and Mexico, as well as Brazil and Chile. (Here’s an interactive scatter plot to make it clear.) Same age, same test, different cultures.

Short of moving to Jordan (the OECD champ for girls outscoring boys), the researchers do have some suggestions they believe are wise even if less than magical. One is that interactive teaching methods—the ones fostered by these concept tests—raise scores for both men and women: “These teaching techniques improve student gains on these tests by four times as much as the size of the gap between men’s and women’s scores,” the release summarizes.

Good teaching is a rising tide that lifts all boats—there’s a stereotype that does some good.