San Diego Unified’s class of 2016 set a record-high graduation rate of 91 percent. Graduation rates at individual high schools are climbing too. Recently, 13 San Diego schools made a list of best high schools in America, in part for their high graduation rates.

But a closer look at individual high schools reveals a trend that might seem contradictory at first glance: Schools whose graduation rates are rising are simultaneously losing a significant number of students to charter schools and schools in other parts of town.

Lincoln High, for example, posted an 84.7 percent graduation rate—the highest since the school re-opened in 2007. But nearly 60 percent of the students who started as freshmen at Lincoln High transferred to another school before they completed their senior year. More students left Lincoln than any other traditional high school in the district.

Last week, we reported that 581 students left a traditional San Diego Unified high school during the 2015–16 school year and landed at a charter school. Of those who left, 34 percent were a year or more behind at the time they transferred. The data included students from all grade levels.

Neither San Diego Unified nor charter schools are breaking any rules as thousands of students shift from one to the other. But the relationship also allows charter schools to act as a safety valve for the district.

For the first time last year, San Diego Unified made a series of college-prep courses a high school graduation requirement. Students can avoid these classes, however, and still come away with a diploma simply by transferring to a charter school.

District officials maintain that the number of students who are leaving had nothing to do with the district reaching a 91 percent graduation rate.

Ron Rode, a senior district manager and point person on academic data, pointed out that a higher percentage of students who left the district were on track to graduate than the percentage of those who left and were not on track. In other words, the group of low-performing students who left were outweighed by the students who were on track to graduate when they left.

But that doesn’t answer the more fundamental question of why so many students are leaving Lincoln and other district-managed schools.

Explanations offered thus far by district officials—that San Diego is simply a place where students come and go—overlooks other factors district officials have themselves noted about Lincoln High. Namely, that a high percentage of ninth graders entering Lincoln High read at a second-grade level.

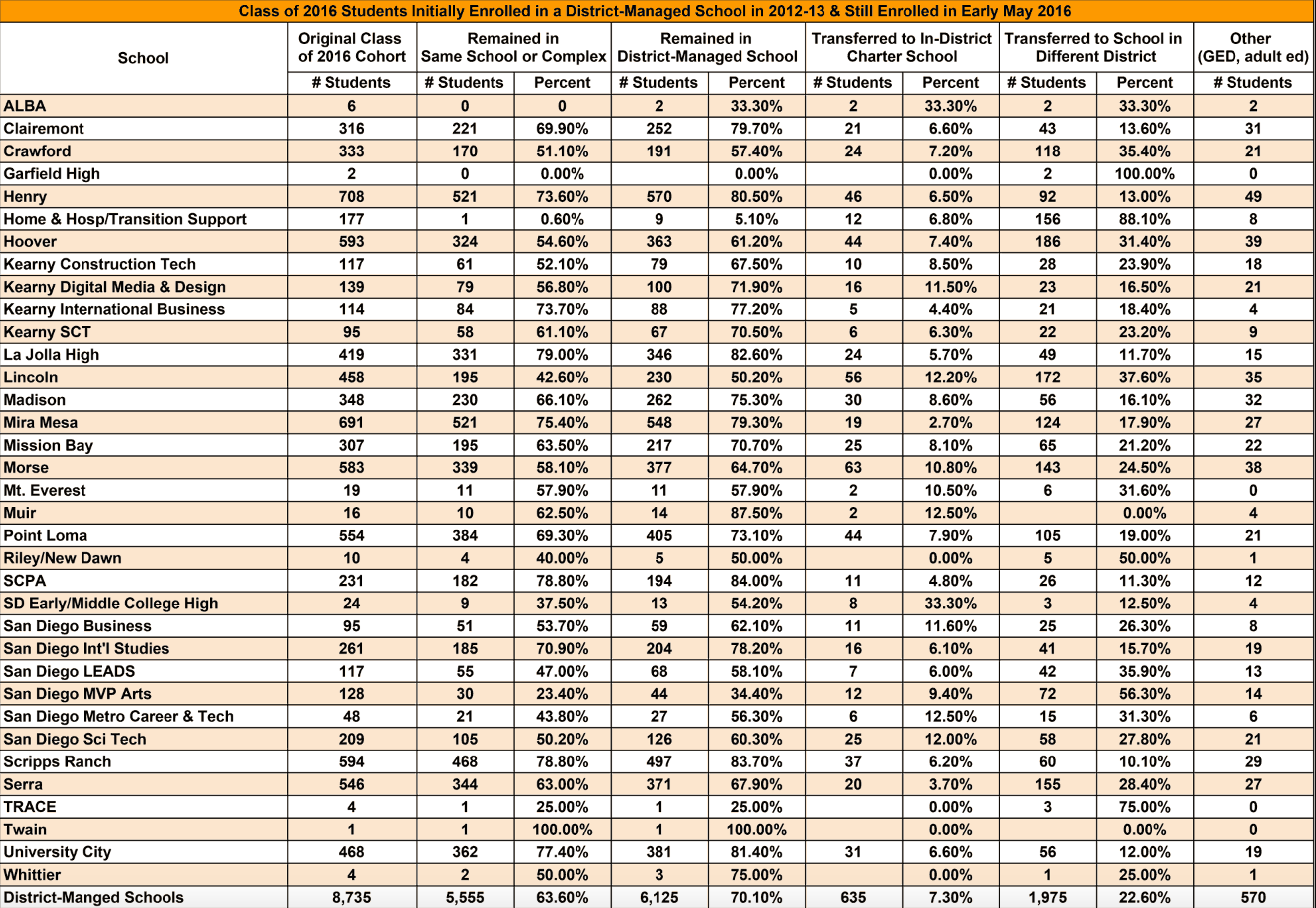

Below, you’ll see the number and percentage of students who left district-managed high schools between fall of 2012 and spring of 2016, which corresponds to when the class of 2016 entered and completed four years of high school:

According to district records obtained through public records requests, more than 57 percent of students who entered Lincoln as freshmen in 2012 left before they completed their senior year. That’s a higher rate of departure than any other traditional high school in the district.

Just over 12 percent of those who left transferred to a charter school in San Diego Unified’s boundaries—most leaving for Charter School of San Diego, a charter school that offers online classes and an independent study program tailored to students’ schedules and goals.

Another 172 students, or 38 percent, left the district altogether. Those students could have moved to a different school district or transferred to a charter school outside of the district’s boundaries.

At the same time, Lincoln’s graduation rate jumped 6 percentage points—from 78 percent to 84.7 percent.

Cindy Barros, head of Lincoln’s parent-teacher organization, suspects most students are leaving Lincoln because they’re behind in credits.

“I think a lot of kids are leaving behind they came in behind, and the school couldn’t fix them. The kids are already coming in so far behind and credit-deficient that the school can’t correct them. They don’t have enough classes set up to help them. We need to look at our middle and elementary schools, and what they’re doing to prepare our kids for high school,” she said.

That would fit with what Cheryl Hibbeln, director of secondary schools, told a group of Lincoln parents earlier this school year. When parents asked Hibbeln to explain the reasoning behind an upcoming change in class schedules, Hibbeln told them that students needed extra time because too many arrive reading at a second-grade level.

Staff members at Lincoln High did not respond to questions about why so many students are leaving the school. But under-enrollment has been one of the school’s chief concerns for the past 10 years.

Lincoln was re-opened in 2007 after a $129 million rebuild. District officials hoped neighborhood students would flock to the newly renovated school. And they did. More than 2,300 students clamored to get into the school when it first opened.

But after a rocky start, Lincoln was never able to gain traction. By last September, enrollment had dropped to 1,447 students.

Problems continue to plague the campus—top among them, leadership turnover. The school has had four principals since 2007 and is currently searching for its fifth.

When students transfer from a traditional high school to a charter school, they are no longer included in the district’s graduation rate.

Earlier this year, it was clear that the latest effort to reboot the school—by offering community college classes to Lincoln students—had backfired. Students who’d signed up for college classes were routed into a remedial math course, whether or not they’d asked for it. Roughly 75 percent of those students ultimately failed the class, which the school’s principal attributed partly to lack of academic support for the students.

In response, San Diego Unified etched out an agreement with the San Diego Community College District to withdraw those students from the class so Fs don’t remain on their college transcripts.

Lincoln’s struggles are well documented, but it wasn’t the only school to lose a high percentage of students and simultaneously see a rise in its graduation rate.

Morse High, also in southeastern San Diego, graduated 95 percent of last year’s seniors and recently landed a spot on U.S. News and World Report‘s 2017 list of “Best High Schools in America.”

Roughly 42 percent of the students who started at Morse left before the end of their senior year. Ten percent of those students left for charter schools and 25 percent left the district altogether.

Hoover High, in City Heights, lost 45 percent of its class of 2016 cohort by May of 2016. A number of Hoover students transferred to nearby Arroyo Paseo charter school.

And while Hoover High landed an 86.7 percent graduation rate and a 4.8 percent dropout rate, Arroyo Paseo’s graduation rate came in at 61 percent last year. Its dropout rate was 24 percent.

When students transfer from a traditional high school to a charter school, they are no longer included in the district’s graduation rate. And when low-performing students drop out after they transfer to a charter school, the dropout counts against the charter school—not San Diego Unified—even if students transfer in their fourth year of high school.

Citing low graduation rates, the San Diego Unified school board recently voted to deny the renewal of Arroyo Paseo’s charter. The school will have to close after June 30th if it doesn’t appeal to the San Diego County Board of Education and emerge successful.

This story originally appeared in New America’s digital magazine, New America Weekly, a Pacific Standard partner site. Sign up to get New America Weekly delivered to your inbox, and follow @NewAmerica on Twitter.