In his 34 years as president of Bard College, Leon Botstein has morphed from wunderkind to elder statesman of higher education. The son of physicians, he studied history with Hannah Arendt at the University of Chicago and earned his doctorate at Harvard before being named president of Franconia College in 1970 when he was just 23. He took the helm at Bard, in upstate New York, five years later.

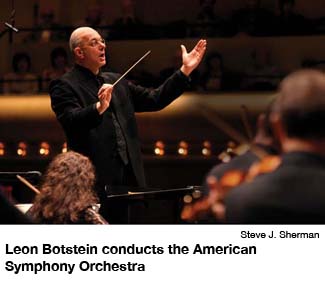

Botstein has bolstered Bard’s performing arts program while recruiting prestigious faculty and creating new graduate programs. He has experimented with restructuring secondary education, started a prison education program and pursued academic partnerships with institutions abroad. Somehow, he also finds the time to serve as musical director of the American Symphony Orchestra and the Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra, leading 40 concerts a year.

Scholar, musician and intellectual provocateur, Botstein is an engaging, free-flowing conversationalist, his eye always on the big picture. He is also a ferocious champion of small liberal arts colleges and a perceptive critic of education-as-usual. He spoke to Miller-McCune in Albuquerque, N.M., in February on a trip to guest conduct the New Mexico Symphony Orchestra.

Miller-McCune:The New York Times recently reported that Harvard had lost 20 percent of its endowment in the collapse of the financial markets, prompting it to freeze salaries and offer early retirement to 1,600 employees. With even Harvard taking these measures, what will happen to other colleges and universities?

Leon Botstein: Harvard represents a portion of American academic institutions where endowments have come to occupy a huge portion of their operating expense. At a place like Harvard, there was a strange period of time in which endowments grew rapidly and the institutions spent a fraction of their earnings. These institutions began to look like banks, not like institutions of higher education. By the time the bubble burst, I would say that Harvard was run more by its investment people and by the professional schools than it was by the faculty of arts and sciences.

These are very wealthy institutions. Take a place like Grinnell or Swarthmore or Amherst, which had more than $1 million-per-student endowments — what were they doing? They’ve hit a tough time because their budgets are completely dependent — 30 percent, 33 percent or 40 percent — on the income from this endowment. Now the endowment has collapsed 30 or 40 percent and they’re in a jam.

I don’t feel particularly sorry for them. These institutions grew without a lot of discipline. A lot of them are taking the opportunity, rightfully, to use a period of economic collapse to get rid of things when they’ve just gone through a time when they could not defend not doing something because of a lack of resources. They had to keep saying yes to everybody. People now have to say, “Well, what’s really important? What really works? What can I get rid of?”

I also think a lot of people in universities got very lazy about focusing on their primary function, which is that of teaching. Once upon a time, senior faculty members did some undergraduate teaching. Now, they do only research.

They don’t talk to even postdocs. Graduate students are poorly taught — the (same) graduate students that end up teaching the undergraduates. It’s a complete loss of attention to the classroom.

I think there’s a very welcome change in the environment ahead. Places like Harvard and Yale and Princeton — the very wealthy places — will take the occasion to really rethink what they’re doing and perhaps do it better, particularly on the undergraduate and also graduate-student level. But these are not poor places, and they’re not at risk. If they have to spend a little capital to make sure the ship doesn’t founder, they’re not in any danger.

But it is the state institutions that have their backs against the wall. They’ve been starved for funding. They can’t raise the tuition against the public particularly. Who’s going to help them? I happened to see an article that said most Americans love their state university because of their sports teams. This is an outrage. This needs to stop. It is an implausible reality. You have to talk to the public and say, “We don’t have universities to field teams.” I think it’s corrupting the environment of the university.

Then you have the community college system, which is the largest-growing and which is a tragedy of its own. It has to pick up the pieces from high school. They’re wildly overcrowded and often do not have real connections to four-year learning. They’re very, very important parts of the system, and they could use some improvement as well. They are a reflection of the fact that in America, we delay real learning too late. A lot of what the community colleges do could be done in high school.

The real problem in American education in my point of view is the way we deal with adolescence. For all the talk of early childhood and preschool, the real locus of crisis in America is from the onset of puberty to the early 20s. That is a kind of black hole for everyone except the very, very gifted and talented. Even with them, we’re not doing as well as we could. We haven’t figured out how to inspire real ambition and a love of learning in the adolescent group, starting with middle school through to really the end of college.

M-M:Neuroscience has recently documented the extent to which the brain is still developing throughout adolescence. Teens don’t have the ability, necessarily, to inhibit bad choices and fully weigh the consequences of their actions.

LB: Everybody knew it. That’s why they put Socrates on trial for corrupting the young. He knew what he was doing. Therefore, I would put a lot of resources into completely rethinking what we do.

We have two public high schools in New York City that follow this, the Bard High School Early College — one on the Lower East Side and one in Queens. We also are running a model school in the Central Valley of California together with the major employer there, Paramount Farms, which has a teacher-training program and also tries to put some of this into practice.

The view we’ve developed through our empirical models is that we should have a two-tier system — elementary and secondary — rather than the three-tier system we have now. I would get rid of middle school. Compulsory schooling would end at 16, not 18 — after 10 years, not after 12. Grades K through six would be the elementary and seven, eight, nine, 10 would be the secondary.

You would essentially end high school at the end of the 10th grade. Then, students would be free to go on to college or to secondary institutions that might focus on specific skills, keeping open the possibility of returning to college. You would go on to take responsibility in a pre-adult manner for your own education.

M-M:So once a student enrolls in the Bard High School Early College program, what degrees have they earned at the end of four years?

LB: At the end of the 12th grade they have a high school degree and an (Associate of Arts) degree. They effectively finish high school at the end of the 10th grade. The kids represent a fair mirror of the city of New York. Over 16 percent are from families that are not born in the United States. They are African American and Hispanic — they represent a diverse school. The first one started in 2001.

M-M: How have the graduates done over time?

LB: They’re fantastic. They’ve all gone to college, with few exceptions. They’ve gone to places like Cal Tech and to the City University of New York. It’s fantastically successful, which is why it’s hugely popular. Both schools enroll between 500 and 600 students each. For each entering class of 160, there are over 3,000 kids wanting to get in. It’s hugely competitive, but it’s done by interview. We don’t do it by standardized test.

M-M: Is anyone following your lead?

LB:There’s a lot of interest. One problem is that it requires a university tuition partner. We’re raising money for this. We’re supplementing what the city provides. It takes a lot of time, and we’re the only ones willing to do this.

We’re doing the same thing for them in the prisons. We give incarcerated men and women A.A. and B.A. degrees in the liberal arts, in mathematics, in philosophy — long-term incarcerated felons. We do this with the cooperation of the prison system.

This goes to the question of the leadership of American universities. Who are in these jobs? Why are we (at Bard), who don’t have two cents to rub together, running the largest educational program? Why do we have two high schools in New York? Why do we have this program in California, Paramount Bard Academy? Why do we have the only liberal arts college in post-Communist Russia?

It’s because the trustees and the leadership of the private institutions at places like Harvard, Yale, Amherst, Grinnell, Carleton — the really top institutions — have been too insular. They are captives of nostalgic alumni. They are captives of a faculty that has gotten used to a trust fund, essentially, so they become risk-averse.

I think universities have a real obligation to improve secondary education in the United States. The president needs to turn to the university community and say, “Do something about the high schools,” the same way that university hospitals took over public hospitals. Do something.

M-M: What do you think accounts for the persistent deficits in math and science achievement in the U.S.?

LB:There has to be a radical change in the way that we recruit and train teachers. One of the problems with adolescence is that in high school they need teachers who are competent in what they do. In math, you need mathematicians.

America sees too much horizontal integration of education, where people talk to teachers in other subjects of the same age group. So sixth-grade teachers know other sixth-grade teachers. But a sixth-grade teacher doesn’t know another teacher in ninth-grade math, 12th-grade math, university math, graduate math or first-grade math.

In America, we use the least-qualified people to teach the beginning subjects. It should be the other way around. Nothing is more important to understanding a subject than grasping its fundamentals. The reason we do so poorly in math and science, by comparative standards, is the teaching is so poor. The people are teaching impressionable people something they don’t understand themselves.

One of the real frontiers, both in pre-college and college education, is scientific illiteracy. There was a famous quip attributed to Richard Feynman, who won the Nobel Prize: “If you can’t explain it to someone in freshman physics, you don’t understand it.” Now there’s truth to that adage, even if he didn’t say it. We graduate routinely from college people who do not have as majors the field of science and engineering. They are completely ignorant of science. They can’t tell you what a stem cell is. They can’t tell you what ozone is. Nor do they understand the consequences of looking at evidence regarding global warming. It’s not whether global warming does exist or global warming doesn’t exist, but what is it all about, and what are the probabilities and likelihoods?

M-M: So you would advocate having would-be teachers focus on their subject matter?

LB:By subject matter. I’m a real opponent of the schools of education. I’d get rid of them completely. They have run their course of utility. You must integrate the teaching of teachers through the disciplines themselves and the faculties of arts and sciences. We need to have in the United States a much more vertical and less horizontal integration. The National Academy of Sciences should be writing the curriculum for biology and physics and math, not state education departments.

M-M:How do the Bard high schools deal with the No Child Left Behind, test-driven curriculum requirements?

LB: What we do is say, “Look, our kid’s getting an A.A./regent’s diploma approved by the state of New York in an institution that’s accredited by the same agency that accredits Harvard and Columbia.” There’s nothing wrong with assessment. It’s necessary to be accredited. We’re getting an imprimatur from a higher source than some bureaucratic test-makers.

The problem with American testing is that it is not an instrument of learning. It’s an idiotic thing. When you give a kid a test, what’s the point of the test? It’s not the aggregate grade. The test is a kind of sudden-death experience about whether you understand what you’re being asked.

The whole multiple-choice-test system is also a scam because it is outdated social science, and it’s designed in a way that has no connection to reality. None of us walk around in the world choosing between preset answers. Then, of course, tests are written with an effort to trick, to outsmart the test-taker.

We need a new generation of testing, which is computer-driven and provides an immediate response. As soon as the kid hits the wrong button, they need to stop the clock and engage the kid in a program that goes through the steps so he understands why he got the wrong answer. What the nation needs to do is to get the textbook companies and computer companies to actually innovate a new generation of interactive tests, which actually teach the kids as they teach the test, so two birds are killed with one stone.

M-M: You have been at this for more than three decades. How have college students changed in that time?

LB: They haven’t changed, except in relationship to the culture. I always ask of every generation of students, what’s their first political memory as a child? I started out my career where the first political memories kids had were when Kennedy was assassinated in ’63. Later, their first memories were of when Martin Luther King or RFK was assassinated. Then maybe their first political memories were Watergate or the Iranian hostages. So it goes.

I think today’s students are far and away more energetic, more committed to studying, more aware of the importance of learning. And the greatest contributor to that has been the computer, the advent of technology as clearly an eye-opening pathway. It’s a subliminal perception that modernity is not to be sneezed at. I started out at a time when modernity, which was represented by nuclear power stations and jet airplanes and rockets and missiles, was replaced by modernity that’s represented by this box that can discover the world or a GPS or a cell phone. There’s a sea change in technology, and that has a huge psychic impact on people.

M-M: Have you been able to put these ideas and perceptions into practice at Bard?

LB: It’s always a work in progress. Institutional change is always a mysterious thing. I’ve had two experiences: One is inheriting an institution with a tradition and the other founding new institutions. I’ve done both. The great thing about founding from the ground up is you attract those students and colleagues who know this is a new enterprise, so this is a self-selecting group of people. It’s like moving into a new house or starting your own business. There’s something exciting about that.

Taking over an existing business or renovating someone else’s building is an entirely different proposition.

It’s a question of the perception of time. To build an institution, one has to think in generational terms. But sometimes the rapidity of changes has to be accelerated because of negative pressures. Take this economic crisis. The real danger is that because of scandals, irresponsibility and greed, the entire nation will become risk-averse. Everyone will hide under the table. There will be no gambles taken because risk and taking gambles will have gotten a bad odor.

The opposite is true. Precisely when people are running away from any kind of risk is when innovation is most needed, but people have to be patient about the gestation time. A good idea does not prove itself in six months. You’ll have to tolerate semi-good ideas lingering — and some bad ideas — in order to get the right idea.

I started in my 20s. When you’re in your 20s, your whole view of time is very distorted. First of all, you think you have infinite time, and you know, the young let time slip through their fingers. As we get older, we try to grab hold of it.

My wife, Barbara Haskell, is the senior curator of the Whitney Museum. When we were first dating in the early 1980s, Georgia O’Keeffe invited Barbara for Christmas at Abiquiu here in New Mexico, so I went with her. Miss O’Keeffe was very old, in her 90s. Barbara must have told her that we were thinking about getting married. Miss O’Keeffe turned to Barbara and said, referring to me as the potential husband, “Don’t let him steal your time.”

I think what she knew as a woman in her 90s is that time is a precious commodity. My second child was killed when she was 8. Six hours before she was hit by a car tailgating a school bus, if you had asked me what I thought my daughter’s life expectancy would be as a young girl on the brink of her eighth birthday, I would have measured it in decades.

Once I was told out of the blue that she was dead, I realized that there are no guarantees about the duration.

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Become our fan.