Shauniqua Epps was the sort of student that so many colleges say they want.

She was a high achiever, graduating from high school with a 3.8 GPA and ranking among the top students in her class. She served as secretary, then president, of the student government. She played varsity basketball and softball. Her high-school guidance counselor, in a letter of recommendation, wrote that Epps was “an unusual young lady” with “both drive and determination.”

Epps, 19, was also needy.

Her family lives in subsidized housing in South Philadelphia, and her father died when she was in third grade. Her mother is on Social Security disability, which provides the family $698 a month, records show. Neither of her parents finished high school.

Epps, who is African American, made it her goal to be the first in her family to attend college.

“I did volunteering. I did internships. I did great in school. I was always good with people,” said Epps, who has a broad smile and a cheerful manner. “I thought everything was going to go my way.”

At first, it looked that way.

Epps was admitted to three colleges, all public institutions in Pennsylvania. She was awarded the maximum Pell grant, federal funds intended for needy students. She also qualified for the maximum state grant for needy Pennsylvania students.

None of the three schools Epps was admitted to gave her a single dollar of aid.

To attend her dream school, Lincoln University, Epps would have had to come up with about $4,000 per year, after maxing out on federal loans—close to half of what her mother receives from Social Security. It was money her family didn’t have, she said.

Public colleges and universities were generally founded and funded to give students in their states access to an affordable college education. They have long served as a vital pathway for students from modest means and those who are the first in their families to attend college.

But many public universities, faced with their own financial shortfalls, are increasingly leaving low-income students behind—including strivers like Epps.

It’s not just that colleges are continuously pushing up sticker prices. Public universities have also been shifting their aid, giving less to the poorest students and more to the wealthiest.

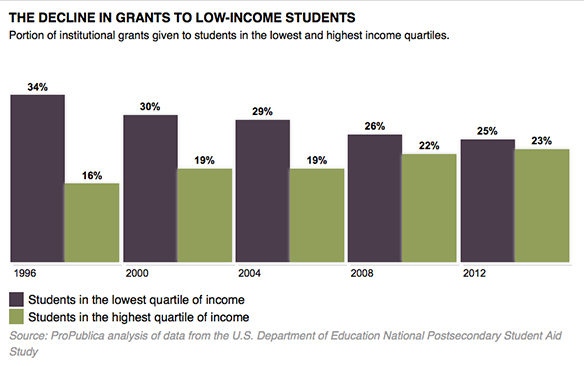

A ProPublica analysis of new data from the U.S. Department of Education shows that from 1996 through 2012, public colleges and universities gave a declining portion of grants—as measured by both the number of grants and the dollar amounts—to students in the lowest quartile of family income. That trend has continued even though the recession hit those in lower income brackets the hardest.

Attention has long been focused on the lack of economic diversity at private colleges, especially at the most elite schools. What has been little discussed, by contrast, is how public universities, which enroll far more students, have gradually shifted their priorities—and a growing portion of their aid dollars—away from low-income students.

State schools are typically considered to offer the most affordable, accessible four-year education students can get. When those schools raise tuition and don’t offer more aid, low-income students are often forced to decide not just which college to attend but whether they can afford to attend college at all.

“The most needy students are getting squeezed out,” said Charles Reed, a former chancellor of the California State University system and of the State University System of Florida. “Need-based aid is extremely important to these students and their parents.”

There’s no data on the number of needy but qualified students who are “squeezed out” and don’t make it onto four-year college campuses. But what is clear is that while the number of needy students has been growing, state schools have not kept up.

Over roughly two decades, four-year state schools have been educating a shrinking portion of the nation’s lowest-income students, according to an analysis of Pell-grant data by Tom Mortenson, a senior scholar at the non-profit Pell Institute. The task of educating low-income students has increasingly fallen to community colleges and for-profit schools.

“One of my charges was to go after what I would call pretty good out-of-state students. Not valedictorians, not the top of the class. Students who you didn’t have to give thousands and thousands of dollars to in order to get them to enroll.”

Epps’ top choice, officially known as The Lincoln University, is about an hour’s drive from Philadelphia, and was one of the nation’s first historically black colleges. Founded in 1854 to serve African Americans excluded from other colleges, the school became a public institution in the early 1970s, when the state legislature deemed its mission to be “completely compatible with the needs of the Commonwealth.”

All of the school’s own aid typically goes toward athletic or merit-based scholarships, regardless of students’ needs. In the 2009-10 budget, for instance, most of the roughly $3 million in institutional aid went to four specific “merit-based” scholarships—and the rest to athletics, international students, and study abroad, according to data supplied by Lincoln. The only need-based aid available to students is through separate donor-supported scholarships, some of which are earmarked for needy students, said university spokesman Eric Webb.

Aid given based on merit or other factors could still go to needy students, but that doesn’t appear to be happening much at Lincoln.

Data made available by the non-profit Institute for College Access & Success show that 84 percent of the school’s grant dollars in the 2009-10 school year did not go to meeting students’ needs. (The data does not include athletic scholarships and certain other forms of aid.)

At Epps’ second choice, Millersville University of Pennsylvania, two-thirds of aid dollars in 2010-11 went to students who had no documented need for it, according to the latest data available. (East Stroudsburg University of Pennsylvania, the third school that accepted Epps, did not provide a breakdown of institutional grant aid.)

Why have public universities across the nation shifted their aid?

“For some schools, they’re trying to climb to the top of the rankings. For other schools, it’s more about revenue generation,” said Don Hossler, a professor of educational leadership and policy studies at Indiana University-Bloomington.

To achieve these goals, schools use their aid to draw wealthier students—especially those from out of state, who will pay more in tuition—or higher-achieving students, whose scores will give the colleges a boost in the rankings.

Private colleges have been using such tactics aggressively for some time. But in recent years, many public colleges have sought to catch up, doing what the industry calls “financial-aid leveraging.”

The math can work like this: Instead of offering, say, $12,000 to an especially needy student, a school might choose to leverage its aid by giving $3,000 discounts to four students with less need, each of whom scored high on the SAT, who together will bring in more tuition dollars than the needier student.

Those discounts are often offered to prospective students as “merit aid.”

Despite its name, “merit aid isn’t always going to the very best students,” Hossler said. “It’s an intentional strategy to help offset the loss of state support.”

Hossler knows this world firsthand. For years, he carried out such strategies as vice chancellor for enrollment services at Indiana University.

“One of my charges was to go after what I would call pretty good out-of-state students,” he said. “Not valedictorians, not the top of the class. Students who you didn’t have to give thousands and thousands of dollars to in order to get them to enroll.”

Indiana University is not alone in thinking about financial aid this way. Consultants who work with schools on financial-aid strategies said they’ve seen an uptick in interest from public universities in recent years, with many focused on generating more revenue.

“When public [universities] come to us individually now, they won’t admit it, but they’re all looking for the same thing—smart students who can pay,” said an industry consultant who asked not to be named.

Another industry consultant, Mary Piccioli of Scannell & Kurz, said many of her firm’s public-school clients are looking to use financial aid “to positively impact the bottom line.”

College officials often argue that attracting students with more resources means they’ll have more aid to redistribute to those in need.

“There’s certainly some truth to that,” said Donald Heller, dean of Michigan State University’s College of Education, who has researched institutional-aid patterns extensively. “But I don’t think that’s really the motivating behavior for many institutions. The more dominant motivating behavior is interest in high-achieving students, which will help them with institutional prestige.”

Epps, apparently, didn’t generate that sort of interest.

She was in her high school’s computer lab, checking her email, when she saw the message from Lincoln University laying out her financial aid package: a mix of state and federal money but nothing from Lincoln.

“Once I saw it, I knew it wasn’t the amount that I needed,” Epps said. “Right away I knew it.”

Epps had been getting guidance from Philadelphia Futures, an organization that helps low-income high-school students get into and complete college. When she went through the cost calculations with a coordinator there, it became clear: The money simply didn’t add up.

At first, Epps said, she blamed herself for not qualifying for aid. She felt like a failure.

“I was kind of upset because I felt as though I worked so hard,” she said. “I kept thinking how I’m not a good test taker.”

Epps had scored a combined SAT score of 820 on math and critical reading. In fact, that’s solidly in the middle of Lincoln’s score distributions for many years, according to data reported to the U.S. Department of Education.

But what Epps didn’t know is that the school had committed to “continuously improving its SAT and GPA averages for incoming cohorts”—as language found in a strategic planning document put it. She also didn’t know that the school had been spending the majority of its financial aid on students who would help bring up those averages—regardless of whether they needed the money.

“To attract top students to your institution, you have to be able to offer them a competitive scholarship package,” said Lincoln University President Robert Jennings. “That’s usually a full-tuition scholarship, that’s a private room sometimes or laptop computer, or a whole bunch of other perks. That’s what schools do. All schools do it.”

Rather than giving small discounts to many students, as many colleges do, Lincoln focuses on giving free rides to top scorers—as a Lincoln admissions flyer lays out.

The strategy seems to have worked. Lincoln University has raised its scores in recent years. In 2002, half of Lincoln’s incoming freshmen scored between a 360 and 460 on the math section of the SAT. In 2012, half of students scored between 410 and 490.

The boost in scores has been no accident, according to Jennings. He said it was a mandate from the Board of Trustees.

“They wanted to increase the SAT averages of students coming to Lincoln,” Jennings said.

And what about students who may have once been a natural fit but aren’t hitting the higher scores? The school still wants to serve some of them—”because of our historical mission,” explained Jennings. But Lincoln has also increasingly been “trying to steer that lower tier of students—students who need much more help—into community colleges,” he said.

Jennings doesn’t see this as a departure from the school’s mission to provide public access. “Absolutely not,” he said. “That’s why you have community colleges. They, too, are public institutions, and we have built collaborative relationships with them.” He added that the school recently launched a campaign to raise more money for scholarships, some of which will go to providing more need-based aid.

Like Lincoln, both Millersville University and East Stroudsburg University—the two other colleges that accepted Epps—have created strategic planning documents that include language reflecting a desire to move up academically.

In a 2010-15 strategic planning document, East Stroudsburg University outlined the goals of becoming “more selective in each new year” as well as fostering “strategic alignment of financial aid” to better attract top students.

“High-achieving and access are not mutually exclusive,” said spokeswoman Brenda Friday. “As such, we look for and recruit students who present both. We also recruit these groups separately. There are funding possibilities available for both groups of students.”

East Stroudsburg and other regional public colleges are in a tough spot. Many don’t have very much aid to give, and most serve a higher percentage of needy students than more prestigious public flagship universities, which have more money from endowments, research and fundraising. It’s a common phenomenon in higher education—students with less money relegated to institutions with less money.

In Pennsylvania, as in most states, public higher education has faced steep cuts, especially since the most recent recession. Over the last five years, the state has cut funds for higher education by 18 percent. At public institutions, that’s worked out to about $2,000 less in state and local support per student—a 32 percentage-point drop, according to data from the State Higher Education Executive Officers.

“All the arrows point in a direction that shows what we are out doing now is raising revenue. The old business model has sort of broken down,” said Patrick Callan, president of the Higher Education Policy Institute and formerly the head of state higher-education boards and commissions in Montana, Washington, and California.

“There have probably been no winners from all of this,” Callan said. “But the biggest losers were those who were disadvantaged on the front end.”

In high school, Epps went by the nickname “Neeks” with most of her friends. They were a mixed group. Some, like her, fostered hopes of attending college. Others just wanted to finish school and get a job.

Though she loved high school, Epps said that looking back she realizes that despite her own efforts, she didn’t get the best education.

About a third of the students at her high school didn’t graduate. After she left, the school was among roughly two dozen shuttered by the chronically underfunded School District of Philadelphia.

“On a couple of levels, systems are failing these students,” said Ann-Therese Ortiz, who worked with Epps as director of pre-college programs at Philadelphia Futures. Low-income high-school students could put in the same effort as their better-resourced counterparts, but “even with the same effort, it simply doesn’t yield the same fruit. And then there’s limited access to the same opportunities, because they’re not receiving the same educational foundation that really opens those doors.”

Those disadvantages can also show up in test scores. A substantial body of research shows that SAT scores are strongly correlated with family income.

“How do you separate merit from privilege?” asked Jerome Lucido, a professor and executive director of the University of Southern California’s Center for Enrollment Research, Policy, and Practice. “Merit needs to be tied to mission, not just who got a higher test score. We already know that has a direct correlation with family income.”

But the SAT and other tests are still crucial to how publications such as U.S. News & World Report and Barron’s formulate college rankings, which are widely regarded as measures of prestige.

Not surprisingly, colleges are constantly working to move up the lists. A prospective student flipping through Barron’s 1995 college-rankings guide would have found about 90 public institutions in the top three tiers of competitiveness and more than 170 in the less competitive or non-competitive tiers. In the 2013 guide, that top tier has grown by more than 40 colleges—about 46 percent—and the bottom tier has shrunk by 60.

“The whole system is constantly moving up, going upstream to get better and better students, and get students who can pay,” said Anthony Carnevale, director of Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce. “It all looks great for the press release. But you’re systematically leaving people behind.”

Carnevale, who has authored many studies analyzing this shift, likens the state of higher education to “hospitals for healthy people,” competing for the easiest to treat, most lucrative patients, rather than taking on the cases of those who stand to benefit the most. “The question is, are you trying to reach down or not?”

Schools might argue they are—in a way.

Many state schools have in recent years struck what are called “articulation agreements”—partnerships with community colleges that make it easier for community-college students to transfer to a four-year school. In the last two years, Lincoln University has established such agreements with 11 community colleges.

But even with improved transfer pathways, there’s still an inherent risk for students like Epps who “undermatch,” or don’t attend the most selective school they can get into. Low-income, minority, and first-generation students frequently undermatch, research shows, and in doing so, they often end up at institutions with less support and far lower graduation rates.

Without any aid from Lincoln or the other colleges that accepted her, Epps weighed her options and chose a different route. She recently completed her first year at the Community College of Philadelphia—a school where about half of full-time freshmen don’t return for a second year.

“In a way, four-year colleges are asking two-year colleges to do the dirty work of selecting who’s worthy of a four-year college,” the Pell Institute’s Tom Mortenson said. In doing so, four-year colleges are not “taking on the responsibility from the beginning when they’re freshmen and making a real commitment to these students.”

But colleges—even those with an explicit public mission—have mounting incentives to avoid students like Epps. Carnevale points to the dawning of what’s known as the “accountability movement”—an effort by states to reform higher education by tying funding for public colleges to student outcomes and graduation rates. Last month, President Barack Obama announced that the federal government would also be moving in a similar direction—and hopes to eventually tie federal aid to certain performance measures.

Unless policymakers build in some incentives to take on more students at the margins, the accountability movement could drive schools further away from low-income and minority populations, which have lower graduation rates overall, Carnevale said. “The whole logic of this industry—and the reform of it as well—excludes low-income and minority students.”

While colleges strive to enroll wealthier and better-performing students, the demographics of the nation’s high-school graduates are moving in a different direction: As a group, tomorrow’s high-school graduates will be more racially diverse and more low-income than today’s.

“There is a significant misalignment. And I think the misalignment’s going to continue to grow,” said David Tandberg, an assistant professor of higher education at Florida State University who previously worked in the Pennsylvania Department of Education.

“The public really, really benefits from a first-generation student going to college. All sorts of wonderful outcomes come from that,” Tandberg said.

A more educated workforce has widespread benefits: It leads to more earning power for those who graduate, a stronger tax base for the state, and greater potential for economic growth in the future.

Public universities have the task of “balancing institutional striving with the public’s needs,” Tandberg said, which “are often two very different things.”

Epps still remembers going out and buying a new button-down shirt, slacks, and dress shoes the night before her high-school graduation. She remembers the nervousness she felt the next morning, and the tinge of sadness.

“I was going to miss my friends. We had been together for four years, and we were all going in different directions,” she said. “I didn’t know how life was going to turn out.”

At graduation, in her white cap and gown, she was the mistress of ceremonies, introducing each of the speakers and making sure the ceremony flowed. She read out the theme of the year’s graduation, a rephrasing of a Thoreau quote: “Go confidently in the direction of your dreams. Live the life you have imagined.”

She’s certainly trying. Community college started up again last week. Epps has already signed up for a full schedule of six classes.

A year from now, she hopes to transfer, finally, to a four-year state school and eventually to get a bachelor’s degree. She’s thinking she might want to study accounting.

Jonathan Lin contributed research to this article.

This post originally appeared onProPublica, a Pacific Standard partner site.