As it pushes historic levels, inequality has become a hot topic. Activists have organized around the rich-poor divide, with “The One Percent” and “The 99 Percent” becoming a part of everyday language. The president made inequality a focus of this year’s State of the Union address and called for a new “middle-class economics.” And a French economist, Thomas Piketty, reached the top of the American bestseller list—when did that last happen?—with a dense volume called Capital in the Twenty-First Century that has jump-started a global conversation about the distribution of income and wealth.

Piketty’s detailed research shocked some: As he noted, the United States today is characterized by “a record level of inequality of income from labor (probably higher than in any other society at any time in the past, anywhere in the world).” But it was not necessarily a big surprise to those of us in California: As with demographics, the Golden State seems to have foreshadowed national trends.

California, for example, is the home to more super rich than anywhere else in the country—and it also exhibits the highest poverty rate in the nation, when cost of living is taken into account. Income disparities in the state of California are among the highest in the nation, outpacing such places as Georgia and Mississippi in terms of the Gini coefficient, a standard measure of inequality.

But it’s not just the extremes—with wages falling and insecurity rising, the middle class is also squeezed. And, as it turns out, none of this is good for economic growth: A new wave of research, including from the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, has been finding that high levels of inequality and racial and class segregation are actually associated with slower and less sustainable growth, providing at least one explanation for the state’s subpar economic performance.

Despite America’s reputation as a land of opportunity, intergenerational earnings elasticity is higher in the U.S. than in Canada, France, Germany, and the Scandinavian countries.

To be clear, some degree of income inequality is to be expected—people have different talents, skills, and predilections, and markets will reward these in different ways. But there are serious consequences when things tip too far in one direction, as seems to be the case for California and the nation. Increasingly, inequality limits our economic potential, threatens our democracy, and even cuts into our life expectancy.

The stakes are high and the solutions are emergent. Some reasonably point to reining in excess wealth—after all, as the California Budget Project has noted, in 2010, the incomes of California’s 41,000 millionaires added up to nearly $144 billion, seven times the income needed to lift every Californian out of poverty. But any real solution also needs a broader strategy to raise the floor on wages and employment standards, create pathways to good jobs that include efforts targeting underrepresented groups, and encourage a new vision of more inclusive growth.

WHY THE GAPS?

For most of the 20th century, California had its share of rich and poor, but they were the outliers on either side of a broad middle class. The California Dream was the American Dream with a destination. While people no longer came to California to strike gold and stumble into riches, they did come to build a stable life for themselves and their families: a promising education, a good job, a home, a car. From around the country and around the world, migrants came seeking employment in our factories, and homes in our cities and suburbs. Stable, middle-class jobs—and generally rising incomes—were the norm.

Beginning in the 1980s, the rich began to pull away from the rest. Between 1979 and 2012, California’s top one percent nearly doubled their incomes, increasing by 189.5 percent, while incomes for the other 99 percent actually fell by 6.3 percent.

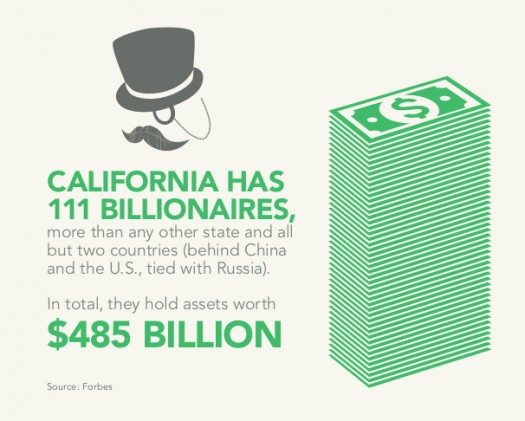

The widening gap has many causes. As California, through Silicon Valley, led the world into the digital age, productivity rose to unprecedented levels. But virtually all of the economic benefits went to those at the top, partly because of the spectacular wealth created by the tech sector. In just the last 10 years, California tech companies added at least 23 billionaires to the list of richest Americans—Twitter alone boasted of creating 1,600 millionaires overnight when it went public 15 months ago. The state now has 111 billionaires; if we were a separate country, that would put us behind only the U.S. and China, and tie us with Russia.

Of course, increasing inequality of income and wealth might be less objectionable if it was associated with mobility—that is, if those on the bottom had a good chance of making it to the middle or the top. But while there are surely individual success stories to be celebrated, these stories are the exception in an economy where it is harder and harder for most people to get ahead. Despite America’s reputation as a land of opportunity, intergenerational earnings elasticity (a measure of how likely you are to be stuck in the income group in which you were raised) is higher in the U.S. than in Canada, France, Germany, and the Scandinavian countries, and just a bit better than in the United Kingdom or Italy.

Part of the problem is that education matters more than ever. Data from the Economic Policy Institute indicate that real wages for those Americans with less than a high school education declined by more than 20 percent between 1979 and 2011, while wages for those with a college degree rose by 12 percent and wages for those with an advanced degree rose by 20 percent over the same period.

This would suggest a need to ramp up our education level—but quality public education appears to be under threat. More and more of the rich insure their children’s own future by placing their kids in private schools or better-off public schools, while the poor are left in struggling schools where graduation rates have fallen to crisis levels and college placement rates remain significantly lower. For example, in 2012, while 81.5 percent of U.S. higher-income high school completers enrolled in college in the following year, only 52.1 percent of those who were low-income did the same.

IT’S NOT JUST CLASS

In an economy where getting ahead is harder, race matters. While California is pulling apart across the board, the average net worth of African Americans is just 14 percent that of whites, and for Latinos just 15 percent that of whites. Because of inadequate retirement savings, African Americans and Latinos over 65 are more than two-and-a-half times as likely to live in poverty as whites. And while education is important, it isn’t everything: People of color with a bachelor’s degree or higher in California still earn five dollars less per hour than their non-Hispanic white counterparts.

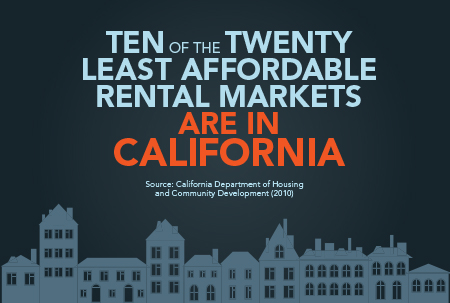

The racial gaps are also reflected in homeownership rates, with homeownership being the major way in which Americans typically amass assets to make their long-term futures more secure. Only 37 percent of African-American households and 44 percent of Latino households are owner-occupied, compared to 64 percent for whites, partly because communities of color were so ravaged by the foreclosure crisis. But it’s not just communities of color that are housing-challenged: California now has 10 of the 20 least affordable rental markets in the country.

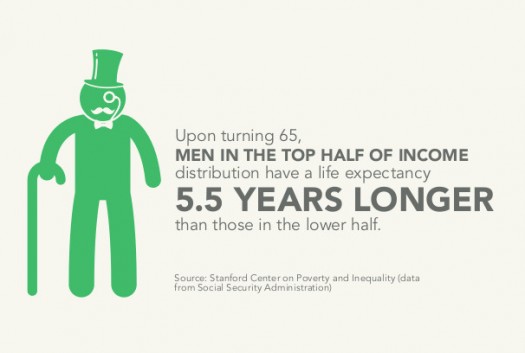

Indeed, place matters as well. Californians in the richest neighborhoods of the state have nearly 12 years additional life expectancy compared to those in the poorest communities. Life expectancy also varies by income and race. Upon reaching age 65, men in the top half of income distribution can expect to live 5.5 years longer than those in the lower half of incomes. African-American babies are 2.6 times as likely as white babies to die before their first birthday.

And place matters in an even larger sense, with broad swaths of coastal California—including the Bay Area, part of Los Angeles and the Central Coast, and Orange County and San Diego—generally doing much better than those in inland California. This spatial separation by income also occurs in our daily lives: In 1970, for example, 65 percent of Americans lived in middle-class neighborhoods, while only 15 percent lived in very rich or very poor neighborhoods. By 2009, only 42 percent lived in middle-class neighborhoods and 33 percent lived in neighborhoods at one of the extremes.

A NEW CALIFORNIA CAN BE HAD

With Californians being pulled further and further apart by income, race, and place, it may be easy to wonder if we will ever get back to the Dream that lured so many here.

But that sort of pessimism is not really part of the California story. This is a place where people came to remake themselves and achieve their ambitions. It is a state that created an affordable, post-secondary educational system that became the envy of the world. It is the place that has led the way to tackle climate change and build a green economy.

Twenty-first century California also needs to lead on combining innovation with inclusion, high-tech with high need. To do this will require that we be as inventive with our public policies as we have been with our software. It will require bridging the gaps that have emerged and growing the recognition that leaving so many behind erodes both our economy and civil society.

The divide between rich and the rest, and the steadily shrinking aspirations and realities of the middle class, have transformed life in California. But Californians have never been passive in the face of challenge—and the first step to addressing our crisis is to have an honest conversation about what has happened and what we can do about it.

This is a conversation that will necessarily involve not just policymakers, but business leaders, labor unions, community organizers, government officials, researchers and educators, faith-leaders, philanthropic actors, and so many more. And it is a conversation that needs to make its way past boardrooms and academic settings into the public square and public consciousness.

This post originally appeared on Capital & Main, a Pacific Standard partner site, as “The California Chasm.” It is part of a month-long series exploring how economic inequality is transforming California, and what can be done to rebuild our vanishing middle class.