The administration of Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger often resembled an ambitious global think tank that was affiliated with a gym. In the long days between his early morning and evening workouts, the governor tackled every thorny public policy issue by convening with experts from across the political spectrum, and the world. Then he and his diverse team of advisers—from progressive environmentalists to conservative business lobbyists—would synthesize centrist solutions that were unveiled at press conferences heavy on body-building metaphors.

This approach encapsulates what was so promising, and frustrating, about Schwarzenegger’s seven years as California governor. He had a knack for finding the pragmatic middle ground on difficult subjects. But at times, the breadth of his work and ambition made it hard for the administration to focus. That tendency, in combination with political polarization and the difficulties of governing California’s broken system, sometimes made it hard for him to turn his thinking into action.

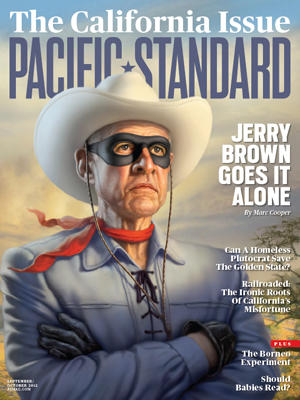

California Issue

Other stories in Pacific Standard‘s special look at California’s effort to live up to its sobriquet of the Golden State include:

The Governor’s Last Stand

The Freethinking Homeless Billionaire and the Flat-Broke State

The Corrections (posting August 28)

So the governor’s establishment of a new think tank at the University of Southern California, the USC Schwarzenegger Institute (along with a professorship), is both fitting, and intriguing. Yes, comedians have had a field day with the idea of an Arnold think tank (“Maria Shriver said Arnold came up with the idea of the think tank while thinking things over as he slept on the couch,” quipped Argus Hamilton), and yes, there is considerable cynicism about whether USC is trading on Schwarzenegger’s fame and fundraising ability (he’s promised to raise $20 million for the think tank) and whether Schwarzenegger is seeking some academic gloss to rehabilitate his image. But a close look suggests his plan is serious and super-ambitious.

Maybe too ambitious, in a familiar way. The institute is devoted to developing “post-partisan solutions”—a big task in an increasingly polarized world—across five policy areas, each big enough for multiple think tanks: education, energy and environment, fiscal and economic policy, health and human wellness, and political reform.

“We’re not going to do all those things at once,” says Bonnie Reiss, one of the institute’s two directors (the other is law and public policy professor Nancy Staudt). “We want to have the flexibility, should a new policy challenge arise, to take action in a new direction.”

Reiss says the institute will achieve such breadth through a host of collaborations—with students who become institute fellows, with policy practitioners from school superintendents to governors, with other think tanks and non-profits. Already, Schwarzenegger is devising collaborations with other parts of the USC public policy school (where the institute will be based) and the film school. It’s not hard to imagine, given the former governor’s ambitions, the institute reaching even further afield—even into the hard sciences. The first of the think tank’s stated principles is: “science and evidence must play an important an important role when finding solutions to policy and social issues.”

Reiss’ presence is one sign of the institute’s seriousness. She’s a former California education secretary and current member of the University of California Board of Regents who has worked with Schwarzenegger for two decades. Among many other successes, she helped turn his LA Inner City Games program into a national after-school program with operations in a dozen cities.

Another good sign is how the USC institute aims to build on other Schwarzenegger policy projects. The USC institute is collaborating with R20, the nonprofit coalition Schwarzenegger founded early last year with the encouragement of United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki- Moon, who wanted to rebuild momentum for climate change work after the failure of the Copenhagen conference in late 2009. The coalition, made up of large states and provinces from British Columbia to India’s Gujarat state, develops, finances, implements, evaluates and replicates low-carbon and climate-resilient projects with economic benefits. R20 is a natural extension of Schwarzenegger’s gubernatorial work on the issue. Unable to convince the federal government to take more action on climate change, he reached agreements on climate measures with other U.S. states and sub-national governments around the globe.

A key player with both the USC center and R20 is Kandeh K. Yumkella, director-general of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization. Yumkella serves on the USC Schwarzenegger Institute’s star-studded advisory board, along with former U.S. housing secretary Henry Cisneros, former Secretary of State George Shultz, former Mexican president Vicente Fox, and Austria’s current chancellor Werner Faymann.

Terry Tamminen, a former California environmental secretary who works with Schwarzenegger on R20, calls the former governor’s aim to harness local and sub-national governments to tackle global problems when national governments are paralyzed, “the emerging Schwarzenegger Doctrine.” Duly, Schwarzenegger has been named a professor in state and global policy.

Schwarzenegger expects to collaborate with other political leaders interested in the marriage of subnational governance and global issues. Former Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley is chairing the Global Cities Initiative, a joint project of Brookings and JP Morgan Chase to encourage collaboration between municipal leaders worldwide on economic issues. And Schwarzenegger’s R20 has close ties to C40, an organization of large cities chaired by New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, a Schwarzenegger friend, that focuses on climate change.

Schwarzenegger formally launches the USC think tank with a symposium on campus in late September; he’ll keynote USC’s global conference in Seoul next May.

His biggest challenges: Can he sustain a “post-partisan” think tank when policy-oriented donors are mostly partisan? At age 65, can he quickly build something that lives after him? Schwarzenegger is determined to create a think tank that not only comes up with ideas—but also works to implement them. Since implementation was the most difficult challenge for his administration, the big question may be not what new lessons the former governor can teach the world, but what lessons Professor Schwarzenegger learned from his time in office.