This story was produced in collaboration with the Hechinger Report.

Anthony Barela, the principal of Vista High School in San Diego, California, had a vivid image of what school could look like after a $10 million grant to reimagine learning: Rolling desks and chairs, with students moving freely and talking about their work. Better attendance, class participation, and graduation rates.

One year later, Barela has watched some of this vision flourish—including new classes and ways of teaching—while other parts never took off.

“Oh, I hate [the furniture],” says teacher Catherine Connelly, who is pioneering a new course in social and emotional wellness. “I don’t know who thought white desks and rolling chairs were good ideas for high school students.”

Vista’s trials and errors started when the school became an XQ Super School Project, with a five-year grant by the national non-profit to bring a personalized-learning approach to the suburban California district. With year one down, teachers, students, and administrators are still negotiating the promise and pitfalls of personalized learning on a large scale, lessons that may shed light on the relatively new reform that so far seems to be facilitating modest achievement gains.

Barela contends that Vista’s approach is making a tangible impact in an area he’s long considered paramount: attendance. Attendance rates among last year’s ninth-grade class were up 15 percent from the previous year’s freshmen, according to Barela, and 10 percent from the same class’ eighth-grade rates. The average grade point average for freshmen was slightly higher (0.2 percent) as well.

This nearly majority Latino city began its experiment with personalized learning three years ago, after a districtwide survey revealed that thousands of high schoolers felt their education wasn’t relevant. District officials theorized that students’ disillusionment with the curriculum contributed to Vista High’s 10 percent dropout rate. In response, they launched an experimental Personalized Learning Academy for 150 juniors and seniors deemed at risk of dropping out.

Grades and attendance rates for students who signed up for the new academy rose slowly over the next two years, giving Vista officials sufficient evidence that their approach could work on a larger scale. They applied for and won the $10 million XQ grant, which meant that they would need to replicate the features that made their academy successful on a much larger scale: creating smaller communities, making changes gradually, giving students more control, and focusing on students’ social and emotional wellness.

Smaller Communities

Vista school officials started by trying to replicate the academy’s intimate structure, in which four teachers shared the same group of 150 students and got a block of time each day to plan lessons together and review who needed additional help. Sharing information helped them develop closer relationships with students and better tailor their lessons.

For the 2017–18 school year, they broke up Vista’s freshman class of almost 700 students into six self-contained “houses.” Teachers say they appreciate the chance to work more closely with the students, along with a small group of their colleagues, and believe it’s helped contribute to a drop in disciplinary incidents.

“Because of the relationships and collaborations between the teachers,” says freshman math teacher Amanda Peace, “those issues are able to get settled a lot faster than they would in a previous year.”

Yet some teachers also say that the intimacy of the house system—in which freshmen often ended up in three or more classes with the same students—caused friction.

While students in the pilot academy chose to join the close-knit community, last year’s freshmen had no choice. When they had conflicts, they didn’t get time away from each other, so Peace says her team decided to switch several students’ schedules midyear.

But even with such frustrations, the house system kept freshmen who would otherwise be scattered across Vista’s sprawling outdoor campus feeling “like a little family,” says 14-year-old, then-freshman Peyton Kemp.

And having small groups of teachers sharing the same students also paid academic dividends.

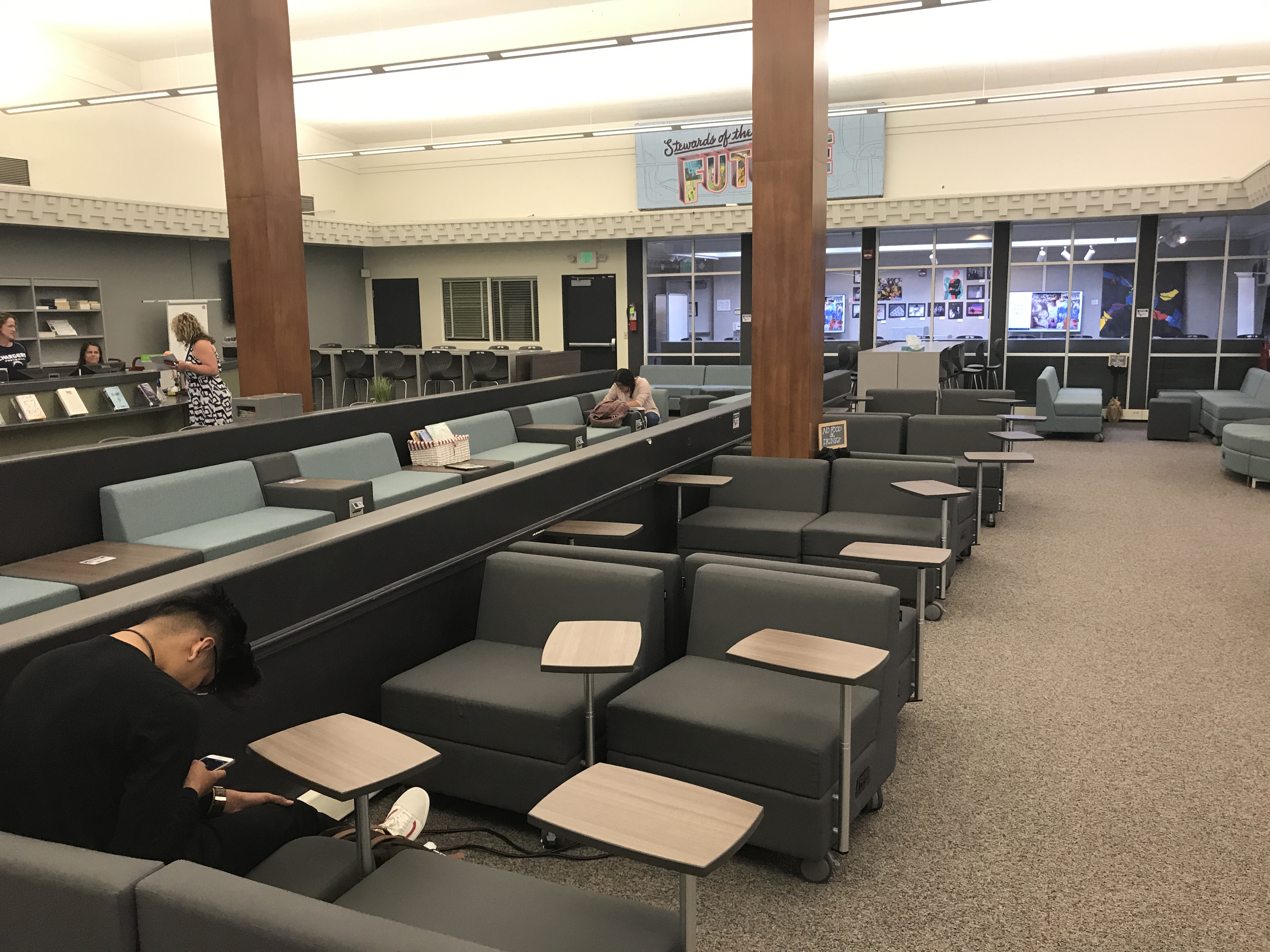

(Photo: Mike Elsen-Rooney/the Hechinger Report)

“I think the students were a little shocked by the connection between teachers,” says freshman science teacher Lexi Kunz. “They hadn’t seen that before. We would have times when they’re working on one assignment and there’d be a very explicit connection in another class, and I think they went, ‘Oh, this is real, they’re really talking to each other.'”

Making Changes Gradually

Teachers and administrators in the academy also found that for change to stick, it had to come gradually; students and teachers both needed time to adjust.

At the beginning of the 2017–18 school year, freshman history teacher Matt Stuckey, one of the school’s most experienced personalized-learning practitioners, told students that change wouldn’t happen all at once.

“Some days, it’s going to feel like what school felt like last year,” Stuckey told them. “Then there’s going to be times when you’re really going to have the independence to show what you’re learning in different ways.'”

More Student Control Over Learning

Personalized learning encompasses a range of techniques meant to give students more control over what they learn and how they learn it. Much of the momentum has come from foundations with roots in Silicon Valley, whose founders believe that a proliferation of cheap technology allows new possibilities for personalizing education. The idea has also appealed to educators who see benefits in letting students learn at their own pace, after years of standardized testing.

In Kunz’s windowless freshman physics class on an April school day, a group of about 15 mixed special and general education students squinted up at a projection of a graph.

“I had a lovely conversation with Ms. Peace about graphing,” Kunz explained to her students. Peace teaches in the same house as Kunz, and had noticed that this group of students struggled when choosing increments for labeling the x-axis of a graph.

Kunz devoted the entire lesson to reinforcing the skill. Students worked quietly—a couple listened to music through headphones—and the special education teacher who co-teaches the course walked around spending additional time with some students.

That kind of communication—in which Kunz and Peace tag teamed their teaching of the same concept—is a clear benefit of the house system and of personalized learning’s approach, and simply wouldn’t have happened in previous years, teachers say.

But communicating with each other about where to focus is just the first step, according to Craig Gastauer, the former science teacher who’s now in charge of training Vista’s teachers in personalized learning.

For example, if Kunz’s reinforcement lesson on graphing had allowed students to fill in the x-axis in the way they thought was correct, then compare answers, they would have understood the process more deeply because they would have found the answers on their own, Gastauer says.

From his tiny office in an out-of-the way corner of the campus, Gastauer says that the whole experiment is about trial and error; he ultimately wants to overhaul the school’s grading system, removing letter grades and switching to “competency-based” diplomas that would allow students more flexibility in how to demonstrate they’ve acquired the knowledge necessary to graduate high school.

“We want to make sure first we have a curriculum that’s inviting to the students where they can work with teachers to co-create parts of the curriculum,” he says.

Teachers have come a long way since the beginning of the last school year, when many say they felt “under the microscope” and fearful they’d be criticized for not adapting quickly enough to the changes, Gastauer says. They felt additional pressure from amped-up media around the XQ grant, which celebrated its 10 “super schools” last September with a flashy national television event featuring actor Tom Hanks.

War, Peace and Chromebooks

History teacher Caroline Billings embraced the changes. Instead of the traditional global history course she’d taught in the past, in 2017–18 she led a “challenge” class in which freshmen design self-directed projects based on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

On an April morning in Billings’ class, students chatted in groups and surfed the Internet on Chromebook laptops, as part of a unit on peace. Later, as a final project, the groups would propose ways to incorporate the study of peace into the 2018–19 history curriculum.

Billings assigned each group of three a different aspect of peace studies to research. One group typed “France” into the Google search bar, another browsed search results for “domestic peace.”

Avery Mortensen, 14, appreciated that Billings started the unit by having students read a critique of teaching peace in history class, and called the class more “student involving” than previous history courses.

Other students struggled with the freedom of toting the personal Chromebook laptops the school gave out. “It’s more like a personal thing when you get distracted on the Chromebook, not the Chromebook itself,” says 15-year-old Emiah Mills.

(Photo: Mike Elsen-Rooney/the Hechinger Report)

Finding the right balance with the new technology is a focus for teacher training. Gastauer instructs teachers to “plan learning and then ask how can tech enhance. Don’t start with the app.”

Before the Chromebooks, Mills had to borrow her grandmother’s computer. Now she gets more done at home, although she admits she also video chats with her friends while working on essays.

Can Wellness Be Taught?

Teachers knew that students would at times struggle with the increased freedom and responsibility of personalized learning, and they were ready with a solution they’d piloted in the academy: “wellness” classes dedicated to helping students cope with social and emotional discomfort.

Wellness teacher Cindy Brooks says the course supports the broader goal of Vista’s personalized learning push “to get those kids that get lost in the shuffle. Try to bring them in.”

Ultimately, wellness class became something of a metaphor for the rollout of personalized learning as a whole, illustrating the challenge of making a concept that worked with a small, self-selecting group succeed on a much larger scale.

Eight teachers volunteered to teach the course and write the curriculum, but they had no idea where to start. “It’s a class that no other place was doing,” says wellness teacher Rick Worthington. They cobbled together curriculum materials meant for guidance counselors and health teachers.

“We’re literally learning as we go along,” Worthington says. “You can know what stress is and what anxiety is, but how do you teach a teenager?”

In the beginning, students were antagonistic. “That’s the worst beginning of a school year I’ve ever had,” Worthington says. The eight teachers were directly encountering aspects of their students’ lives they used to see only from a distance, but had little framework for teaching them coping skills for what came after school.

The wellness class gave teachers a chance to “step back from the content area of teaching to make that a priority,” former English teacher Cindy Brooks adds.

In addition to daily lessons on topics like how to receive a compliment, wellness teachers checked in with students every week about grades and helped mediate conflicts in other classes.

Gradually, students started to look forward to wellness class. “It’s a good break from school work,” says 15-year-old Namrit Ahluwalia. “Regular school days take our mind away from who we actually are.”

At some point in the school year, administrators realized that none of the eight wellness teachers had experience with English Language Learners. ELL specialists like Kim Collier tried to help, but Collier had no experience with the curriculum wellness teachers were creating on the fly.

“We tried to make some adjustments, but the train was moving,” Collier says. This year, Collier will run a training with wellness teachers before school starts to make sure the course is accessible to ELL students.

What Changes Are Ahead?

There will be other adjustments going forward as well. This fall, Vista’s house system will migrate to the 10th grade, and will expand each year until the whole school runs under the new system.

There are still open questions about how the school will shift into its second year. Some freshmen teachers want to follow their current students to the 10th grade. There will also be a new leader: Principal Barela stepped down to be near family in Colorado. He will be replaced by Kyle Ruggles, a former elementary school principal who most recently oversaw academic and behavioral support programs for the Vista school district.

Much of Barela’s vision will remain. And science teacher Blaine Darling says teachers sound different now when speaking about personalized learning. “For the first time, it’s given everyone a common language,” Darling says. “The conversations that are happening are happening outside of staff meetings.”

That’s exactly what Vista is hoping for: a new kind of teaching that will last, long after the grant is spent. It’s why science teacher Gastauer wasn’t upset at criticism of the moving furniture: Already, Vista has introduced a new version with individual desks instead of long tables, and has gotten much better feedback from teachers.

“The focus has always been on our teachers feeling like they’re comfortable,” Barela says, “and making sure the reason we’re doing that is for our students to be able to leave here better off than when they arrived.”

This story was produced in collaboration with the Hechinger Report, a non-profit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.