On June 29th, their last day before summer vacation, the nine Supreme Court Justices declared they would hear arguments in case number 14-981, Fisher v. University of Texas, this fall, with a decision to follow in early 2016. Abigail Fisher, the plaintiff, filed her suit in 2008 after the University of Texas–Austin denied her admission. Fisher, a white woman who had failed to make the GPA cutoff for automatic admission, decided that race must have been the decisive factor. Fisher has since graduated in good standing from Louisiana State University. Nonetheless, she presses her case, which could outlaw affirmative action altogether and further homogenize the already dispiriting socioeconomic conformity of most campuses.

As the New York Times reports, should the Court decide for the plaintiff, “it would, all sides agree, reduce the number of black and Latino students at nearly every selective college and graduate school, with more Asian-American and white students gaining entrance instead.” Anyone who argues that such a decision won’t hurt black communities is being handsomely reimbursed for the trouble.

A new study in the Federal Bank of St. Louis quarterly report plots long-term wealth accrual against race and education, offering statistics that complicate the affirmative-action debate; those who wave the “reverse-discrimination” flag may very well take these numbers as proof that affirmative action has failed. “Compared to their less-educated counterparts,” the authors write, “typical white and Asian families with four-year college degrees withstood the recent recession much better and have accumulated much more wealth over the longer term.” In other words, while higher education generally tracks with higher long-term income and wealth, that proposition holds only among white and Asian families.

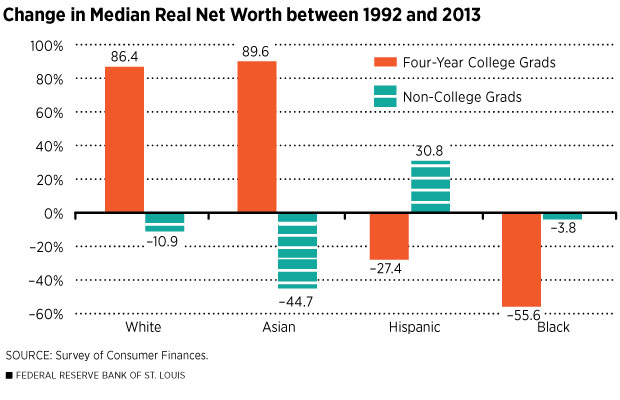

Consider this chart, compiled in the St. Louis report based on the Fed’s Survey of Consumer Finances:

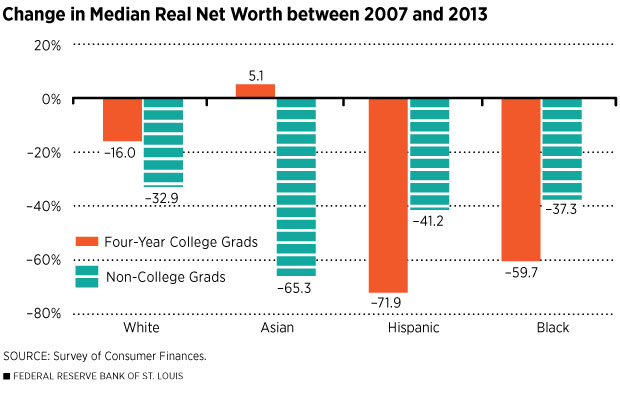

Here are the long-term trends: Over a 20-year period, college-educated blacks experienced a 55-percent drop in wealth and college-educated Latinos experienced a 25-percent drop, while white and Asian graduates, on average, nearly doubled their net worth. Now look at how the Great Recession exacerbated these inequities over a shorter window:

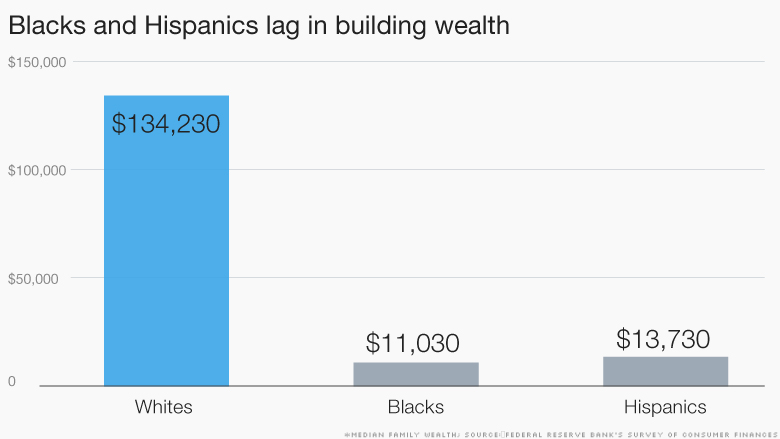

The result? After 20 years of rising income inequality—even among college graduates—whites are out-earning their minority counterparts 10 to one: In 2013, the average white family accrued $130,000; the average black family, $11,000:

Do these numbers suggest that affirmative action has failed? Or do they suggest a more complicated series of factors—deeply entrenched racial bias in hiring coupled with far higher rates of student debt among minorities, higher rates of unemployment, harsher and more frequent traffic stops, and, yes, single-parent, and therefore single-income, households—that create grossly unequal economic outcomes?

The authors of the St. Louis study, William R. Emmons and Bryan J. Noeth, seem to espouse the second view, advising that we find a way to educate our most at-risk citizens without sinking them in a mire of debt. Which brings us from one intractable problem (the race crisis) to another (the student-debt crisis). Formidable, to be sure, but at least we’re now attacking things from the proper direction.

It bears repeating that affirmative action in university admissions buoys the underprivileged considerably without really affecting the acceptance rates for whites, who are both far more numerous and far more likely to apply. In The Shape of the River: Long-Term Consequences of Considering Race in College and University Admissions, William G. Bowen (the former president of Princeton University) and Derek Bok (the former president of Harvard University) established that race-blind admissions policies would increase a white applicant’s chance of acceptance from 25 percent to 26.2 percent—hardly an indication that Caucasians such as Fisher are facing rampant discrimination. By contrast, when Texas introduced a version of race-blind admissions ordinances, the University of Texas–Austin School of Law saw its percentage of black students fall from 20 percent in the early 1990s to less than two percent in 1998. Affirmative action, in other words, costs white students next to nothing. Its removal would impoverish everyone.

The end of affirmative action will be bad news, and not just for black and Latino students. Already, top schools are models of homogeneity when it comes to their students’ socio-economic backgrounds. That’s a problem. Diversity can sound irritating when couched in bureaucratic abstraction, but a genuine education is sort of impossible without it; and for universities to value and welcome diversity doesn’t help only minorities—it enriches the schooling of every matriculating white who grew up among people who looked and talked and thought alike and no one was racist because no one had the chance to be. You can learn a lot from your classmates in college—but if your classmates are just slightly different versions of you, what is there to learn?

Some students, perhaps including Fisher, might not mind going to a school where everyone looks alike. Most of the white undergraduates I know would recoil from such a scenario. I was recently chatting with a woman who attended an elite Seven-Sisters school during those institutions’ golden era. The woman (white) recalled requesting a black roommate before freshman move-in day: “They gave the black student a single,” she laughed, “probably because she wasn’t interested in serving as a component in my social education. My request was dumb in the first place, but we hadn’t grown up with any black neighbors and I just thought it was time to see what other people were like.”

The black frosh in question is now debt-free, a well-regarded professional of the upper middle class with overachieving children to match. At the present juncture, rather than safeguarding whites who feel an aggrieved sense of academic entitlement, our chief concern should be to make college available to the next generation of low-earning, high-achieving minority families. During the current (semi-permanent) election cycle, we’ll hear a lot of pretty speeches about social mobility. It seems ever more clear that unless we fix our system of higher education, we will watch the myth of American mobility continue its hastening descent into the chapter 11 of bankrupt political ideals.