As an ideal and aspiration, multiculturalism has long been a touchstone of an enlightened society. With the end of the Cold War came the prevailing belief among western nations that multiculturalism would mark a peaceful “end of history.” As democracy and globalism continued their global ascendance, the thinking went, tribalism and the social strife it spawned would yield to the values of diversity, inclusion, and tolerance.

But that premise of inclusivity appears to have taken a step backward. German chancellor Angela Merkel announced in 2010 that multiculturalism had “failed utterly,” deeming it unrealistic for Germans and foreign residents to “live happily side by side.” The next year, British Prime Minister David Cameron called for a “muscular liberalism,” one capable of strong-arming Muslin groups into a common culture. A few years later, Donald Trump was campaigning on the promise of keeping immigrants out of the United States.

Assessing the extent of multiculturalism’s decline in a remarkably nuanced Foreign Affairs piece from 2015, British academic Kenan Malik chided Europe for embracing a rigid understanding of multiculturalism that has resulted in “fragmented societies, alienated minorities, [and] resentful citizenries.”

What happened? That depends on whom you ask. Opponents of multiculturalism either posit a necessary incompatibility between the nation-state and ethnocultural diversity, or they argue that immigration was permitted without the demands of integration into the dominant culture. Supporters of the multiculturalism principle insist it has been undermined by xenophobia, an impulse lately instigated by populist authoritarianism and the perverse need to find ethnic scapegoats for problems that are essentially economic. Either way, there’s one fact all have to agree on: Western nations are undergoing irreversible demographic shifts caused by international migration. It is, in other words, about the worst possible time for the ideal of multiculturalism to wither.

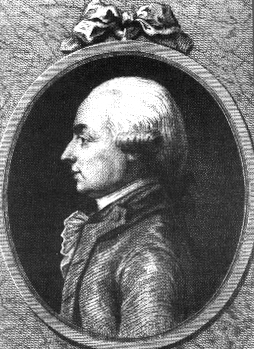

An unlikely model for recovering the multicultural ideal—or at least reminding us what it can be—comes from an equally unlikely place: early America. In the latest edition of Early American Literature, Northwestern University’s Kellen Bolt examines how J. Hector St. John de Crevecoeur, a notable writer and French immigrant, conceptualized the harmonious process of immigrants’ integration into an emerging American society. It’s a story that speaks powerfully to today’s anxieties over immigration and multiculturalism.

Three factors seemed essential to fostering what Crevecoeur saw as a healthy multicultural nation (granted, in the 18th century, that was an all-white multiculturalism). First, what it means to be an “American” was in flux; there was no predetermined standard in which to assimilate. Second, the means of civic integration involved sharing in work projects with native citizens and other immigrants. In other words, participation in civic missions, rather than taking Americanization exams, fostered a more ethnically inclusive polis. Finally, and most critically, this shared work centered on ecological improvement; the outcome of the bonding experience, in short, was good for the commonwealth as well as its soil.

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Crevecoeur’s sketches of the immigrant experience—which Bolt calls “semifictional, semihisorical, semiscientific vignettes”—present “objects of study” through which he was able to “evaluate Americanization practices.” In Crevecoeur’s vision (and imagination), no practice was more pivotal to successful integration than land reform—specifically, draining swamps. Immigrants arriving to the young American nation from Sweden, France, Germany, Scotland, Poland, Jamaica, Portugal, and even Russia would become Americans not through a top-down ideological process, but, in Bolt’s words, through “an ecologically oriented vision of citizenship” based on the back-breaking work of swamp drainage.

The east coast of early America was submerged in swamplands. These microenvironments incubated disease and prevented sustainable agricultural expansion. Improving these swampy areas by draining and developing them into pastures allowed immigrants to participate in representing America as an environmentally healthy place rather than, as it was often suggested, “a terrifyingly chaotic land of death that caused Europeans to degenerate.” Thus Crevecoeur, who moved to British America in 1760 from New France, envisioned a post-revolutionary nation capable of incorporating ethnic difference through shared projects of environmental improvement that simultaneously contributed to the ongoing redefinition of “American.”

Crevecouer, as Bolt describes his ambitions, may have been way ahead of his time. His theory of multiculturalism foreshadows several powerful sociological tenets that have emerged only in the last several decades. His insistence on shared projects speaks to Brandeis University professor Jody Hoffer Gittell’s work on “relational coordination” in the workforce, at the core of which is the claim that, “if effective coordination is to occur, participants must also be connected by relationships of shared goals and mutual respect.” It also reveals a nascent understanding of the unique unity that evolves through “work group diversity,” a cohesion that builds on the assumption that cultural differences can enhance shared experiences. Crevecouer even portents the basic premise of the new field of environmental psychology that considers the positive emotional benefits that arise through positive ecological engagements.

In his Foreign Affairs essay, Malik concluded that, if multiculturalism was going to work, we had to regard minority communities not as “homogenous wholes attached to a particular set of cultural traits, faiths, beliefs, and values,” but rather as “constituent parts of a modern democracy.” With global ecological destruction at an all-time high, there’s an argument to be made for reviving Crevecoeur and opening up the gates.