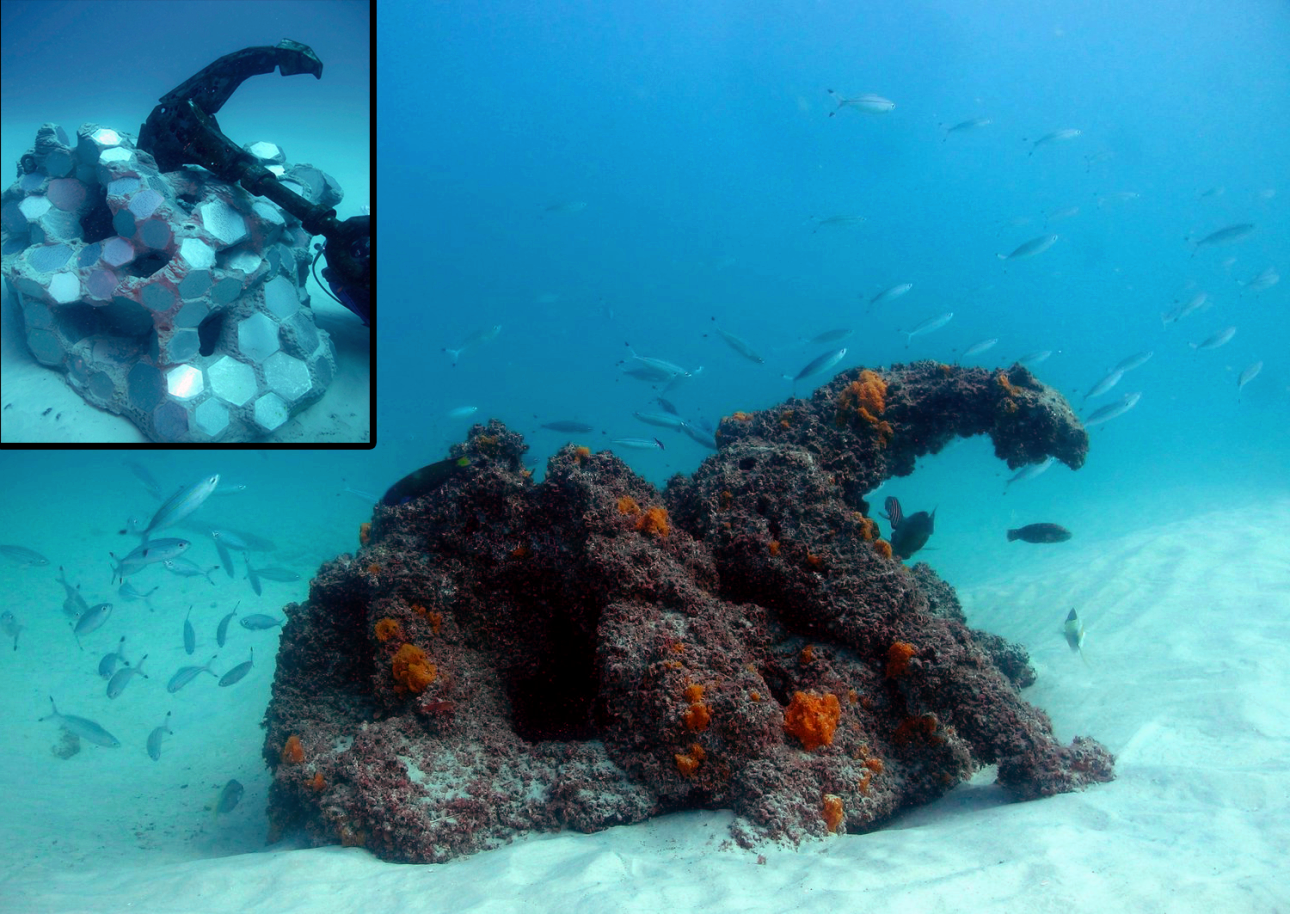

The local fishermen looked on skeptically. From the deck of a small motorboat, scuba divers grabbed odd chunks of ceramic—which could be described as rocky brains stuck on stumpy stilts—and plunged into the aquamarine waters. The dive team assembled the pieces as a few triggerfish circled around to investigate the commotion. After just two air tanks (about an hour each), they had locked all of the items together into the final product: an artificial coral reef.

The 3-D-printed reef, installed at Summer Island Maldives resort last month, is the first of its kind on any of the 1,200 islands of the Maldives. Each of the artificial reef’s ceramic components was 3-D printed with a custom design and then fitted with coral fragments that developers hope will grow across the entire structure.

3-D printers have become faster, cheaper, and more accurate in the past decade, allowing enthusiasts to develop neat trinkets such as toothpaste squeezers and custom pasta makers. Australian entrepreneur Alex Goad had a more ambitious application: 3-D printing coral reefs. He formed the not-for-profit Reef Design Labs to apply the flexibility of 3-D prints to coral restoration research.

“I started Reef Design Labs to support marine research; that’s the main thing we do,” Goad says. “I was interested in ceramic and how it could be used as an ideal material for coral nurseries. So we gave it a go.”

A Customizable Approach to Reef Restoration

RDL calls its patented technique for 3-D-printed coral formation Modular Artificial Reef Structure, or MARS. Instead of using steel or concrete, popular substrates for artificial reefs, RDL prints hollow blocks of ceramic, which can be molded into complex shapes, and fills them with concrete for stability. Divers bring these blocks underwater and fit them together like Legos to form a cohesive and resilient structure.

3-D printing artificial reef structures may sound like a gimmick to draw attention, but Goad suggests several benefits of a custom-design reef mold. Coral begins its life cycle as drifting larvae that search for an unexposed place buffered from predators and water currents. 3-D printing can replicate the intricate structure of existing reefs needed to foster new coral growth. Within minutes, the small alcoves and overhangs of the Maldivian MARS also began attracting curious fish; it may someday provide shelter to crustaceans, sponges, and anemones to form a marine community.

(Photo: Alex Goad)

“[Reef Design Labs] actually designed the structure based on the corals that are most widely growing in the Maldives,” says Aminath Shauna, a native Maldivian and spokesperson for Summer Island Maldives. “[The 3-D-printed reefs] have all these contours and shapes that mimic the natural reefs, so that corals can easily attach themselves … which we can’t do just building regular concrete structures.”

Goad was not the first to construct 3-D-printed reefs; another Australian, James Gardiner, paired up with Sustainable Oceans International to sink blocks of sandstone among sections of a damaged reef system in the Persian Gulf in 2012. The advantage provided by MARS is convenient installation. Rather than using barges to transport beefy chunks of concrete out to sea, divers can slot a customizable set of MARS pieces together by hand to form a sturdy skeleton in shapes inspired by the native coral community.

(Photo: Alex Goad)

Reef Design Labs has applied its technology to support other marine life as well. In June of 2017, RDL participated in Australia’s largest shellfish restoration, sinking more than 18,740 tons of limestone near Yorke Peninsula and then releasing tiny oyster larvae to settle on the new structures. In April of 2016, the lab teamed up with Riot Games to design marine sculptures, including a character from a popular online video game, as appealing hideouts for fish communities. The lab is now working with Volvo to construct a massive seawall to protect Sydney Harbor from erosion.

Each project’s design and implementation solicits input from marine biologists, who monitor the structures to assess which methods yield the most permanent habitats for corals and other reef organisms.

(Photo: Alex Goad)

The materials and methods of installation for an artificial reef must be carefully chosen and prepared, or the structure may do more harm than good for the marine environment. 3-D printing also requires specialized equipment and expertise, and there is a ceiling to how much custom reef design can be scaled up. Goad acknowledges there are limitations to the practice.

“People assume that 3-D printing is going to be some magic thing that is going to save the coral reefs—obviously not. This is to be used for small coral nurseries,” he says. “I was interested in how MARS could help this cause: a permanent structure that had complexity and would allow other reef species [besides corals] to have a home.”

MARS acts as a platform for targeted research on optimal coral farming methods. Prints can be tailored to specific experiments, for instance testing how different techniques of attaching coral fragments affect growth. Such research may help scientists better understand and adjust to the threats faced by coral reefs.

Coral Bleaching Threatens Reefs Worldwide

Corals face a number of threats globally, such as white band disease, coral skeletons dissolving from ocean acidification, and coral bleaching, the last of which has especially affected the Maldives. Warm ocean temperatures stress corals and cause them to eject the algal cells living inside them, which they rely on to produce energy. Prolonged separation kills both coral and algae, leaving nothing but a bone-white skeleton.

“[T]he ecological impacts of bleaching are near-instantaneous and can be severe,” reported Drs. Christopher Perry and Kyle Morgan, who quantified coral loss in the Maldives in 2016. “Such events thus have the capacity to also drive very rapid, and potentially severe, declines … in resultant reef growth potential.”

The Maldives is the largest atoll in the world, a geologic formation composed of thousands of years of coral growth. The nation also boasts the world’s seventh largest reef system—but this is quickly changing.

In 2016, a tremendous El Niño event, a shift in global wind, and precipitation patterns that naturally occur every two to seven years, caused the waters of the Indian and Pacific Oceans to dramatically heat up. This shock of warmth, combined with continually increasing global temperatures, disrupted one-third of the coral cover in Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, and killed an estimated 75 percent of the coral cover in the southern Maldives.

Shauna recalls the summer of 2016 distinctly.

“There’s a reef that we would go for snorkeling near Male [the Maldivian capital],” she says. “It’s a beautiful reef, one of the most healthy reefs that I’ve seen near the capital city. And within a week, we saw it go completely white.”

Corals benefit coastal communities in the Maldives and beyond because they attract fish (and tourists), and they protect coastlines from storms and erosion. The Maldives is particularly vulnerable to sea level rise: the nation’s highest peak on Addu Atoll rises a whopping eight feet above sea level. Shelves created by coral growth act as a wall that buffers the impact of waves, reducing constant flooding as well as erosion of beaches, of which there are precious few left in the Maldives.

“I remember in 2016, when we were swimming it felt like we were in a bath,” Shauna adds. “And it’s not just 2016 … every year it is warmer, and with the El Niño, the coral don’t have time to recover.”

Optimism Despite Dire Global Conditions

Research and creative approaches to reef restoration are a glimmer of hope in the face of global threats that have already destroyed much of the world’s coral ecosystems. Ecologists have identified some corals that thrive in warm waters and others that partner with unique algae to resist high temperatures.

Goad maintains optimism in the toughest of times: “What really keeps me going is how much research is occurring. There is work on understanding heat-tolerant corals and identifying the genetic make-up that resists warming climates … there are also groups looking at how to start coral farms en masse.”

The charisma and flexibility of 3-D printing will not do much to help reefs if ocean temperatures continue to rise to levels at which corals cannot survive. Yet technology like RDL’s can facilitate research to understand how we might adapt to climate change, so Goad is experimenting with approaches to address issues that coastal communities face.

“We’re starting to look into 3D modular design as a wave-breaking technology [to prevent storm damage and flooding]. That’s really interesting because there’s a real need for that in a place like the Maldives.”

Goad said he hopes this work will engage researchers and local communities, demonstrating how easy coral restoration can be and inspiring others to follow. “Installing the structures underwater, it’s really fun,” he says. “Everyone was just loving it.”

And those skeptical Maldivian fishermen scrutinizing the installation? “Now,” Goad says, “they’re starting their own coral nurseries.”

This story originally appeared at the website of global conservation news service Mongabay.com. Get updates on their stories delivered to your inbox, or follow @Mongabay on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter.