In Oregon, where a small group of white people have brazenly plundered public land, the American people are getting a glimpse of things to come. The standoff at the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, after all, is just the extremist edge of a growing anti-conservation crusade bent on dismantling crucial environmental protections and abolishing most federal land. The crusade extends far beyond one government compound, far beyond Oregon’s borders. It involves more menacing figures than the disgruntled ranchers holed up in Harney County. In fact, forget the cowboys—one is dead, some are in jail, and the rest are sure to disperse eventually. It’s the crusaders in suits—the senators, the oil lobbyists, the right-wing legislators—who ought to have your full attention.

Consider, for instance, the anti-conservationists at work in our nation’s capitol. Last year alone, Republican legislators, awash in Big Oil campaign contributions, proposed more than 80 bills or amendments meant to undermine the Endangered Species Act. Some sought to prohibit protection for specific species, others tried to transfer ESA management to the states or exempt the oil and gas industry from the Act’s mandates. President Obama vetoed the items that made it to his desk, but our country’s most essential wildlife law will continue to be a target in 2016.

Lawmakers also threatened the beloved Land and Water Conservation Fund, which pipes hundreds of millions of dollars in oil and gas royalties to local, state and federal conservation projects around the country. Utah Representative Rob Bishop, the chairman of the House Natural Resources Committee and an oil industry favorite, allowed the fund to expire last September. For months, he used it as a bargaining chip to push other Tea Party policies. Congress finally re-authorized the fund during this past December’s budget talks, but only for three years, a short-term fix that’s sure to turn it into a political plaything in future legislative sessions.

The goal, ultimately, is a huge re-distribution of wealth that will take your land, the people’s land, more than 600 million acres of it, and put the majority into state or private hands.

In the most extreme move of all, the 114th Congress embraced the land transfer agenda. Land transfer advocates seek to turn over large swaths of federal public land to the states, where right-wing legislators and developers can do with them as they please. Last March, Senator Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, who has deep ties to oil and gas, pushed through a budget amendment that called for a fund to help finance federal land disposal on a broad scale. Since then, some Republicans, including Bishop and Representative Mark Amodei of Nevada, have formed a congressional team to promote the “return” of federal land to its “rightful owners,” by which they mean state governments, not native tribes.

Congress, alas, is not alone in its anti-conservation zeal. Utah in particular has become a right-wing public lands laboratory of sorts—in 2012, its legislature passed the Transfer of Public Lands Act, which demanded that the feds turn over most of their holdings in the state or risk a lawsuit. The federal government did not comply, and the state is currently preparing the ground for what consultants have estimated will be a $14 million legal effort to requisition federal parcels within Utah’s borders.

The Koch-backed American Lands Council and its leader, a far-right Utah legislator named Ken Ivory, are the major organizing force behind the land transfer movement. Ivory has teamed up with the Koch-backed American Legislative Exchange Council to promote the idea in states across the West. Together, the team has had middling success: Last May, the Nevada state legislature passed a bill calling for federal land transfer, and a number of other states have set up commissions to study the idea, but Utah’s transfer effort is farthest along by far.

Beyond the Koch network, there are other oil industry organizations worth mentioning, like the Western Energy Alliance, a trade group that calls itself “the voice of the industry in the West.” It counts among its members Chevron, Halliburton, and Koch Exploration. Besides backing candidates like climate-denier Jim Inhofe and ferociously opposing federal protection for numerous species, WEA is involved in a public relations campaign meant to undermine the image and credibility of mainstream environmental groups in the West.

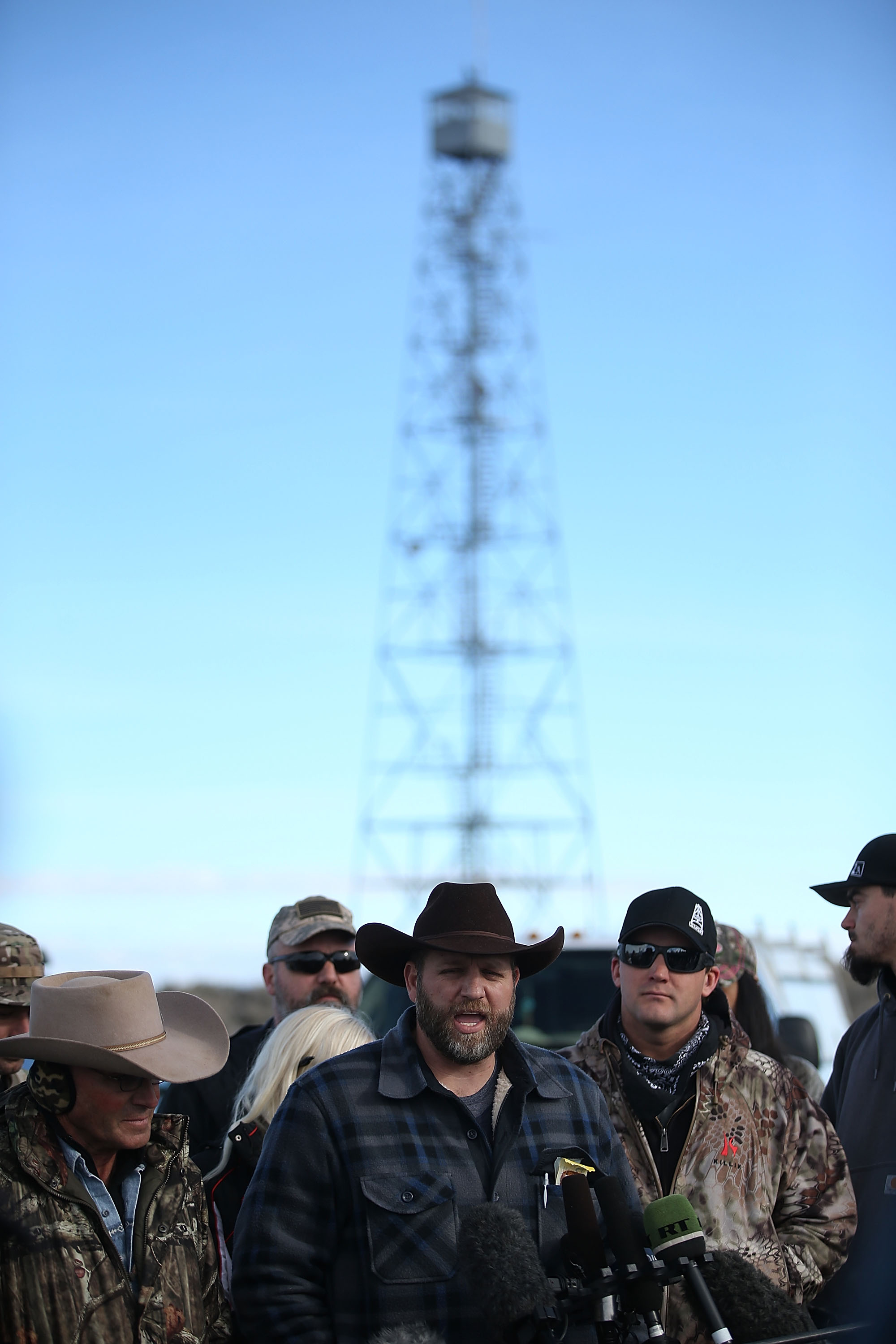

From Capitol Hill to the high country, these undertakings together constitute a multi-pronged and prolonged offensive against American conservation. They seek, above all, to hack away at the political and social values that gave us the Wilderness Act, the ESA, the National Environmental Policy Act, and more. The armed takeover at Malheur was born of this seeping anti-conservation culture, and so it has been instructive to watch some of the more mainstream crusaders respond to the standoff. Like items off an assembly line, the responses come standard: first the obligatory denunciation of Ammon Bundy’s tactics, followed by a full-throated apologia of the armed gang’s grievances.

For instance, in a January blog post, WEA staffer Kathleen Sgamma condemned the Oregon standoff before transitioning into a sharp criticism of “too much federal ownership of land in the West” and the “conservation-only mentality” of some federal agencies. (The latter statement conveniently ignores the thousands of oil and gas leases issued on federal land over the last eight years.)

Bishop had similar sentiments. He distanced himself from Bundy’s violent methods then denounced the Department of the Interior’s “agenda of dogma” and sympathized with the “frustration many Americans feel when they have to deal with the heavy-hand of the federal land agencies.”

Oil and gas trade groups, far-right activists, Republican Congressmen. This is the clique, more or less, that has turned its back on America’s great conservation tradition. What’s to gain? Power and money. One of the militants, Ryan Payne, put it succinctly: “Land is power.” The goal, ultimately, is a huge re-distribution of wealth that will take your land, the people’s land, more than 600 million acres of it, and put the majority into state or private hands. With environmental laws weakened, and federal holdings dissolved, mining interests, oil companies, real-estate developers and more will have easy access to the landscape’s vast riches. As transfer activist Ken Ivory told NPR recently: “There’s more than 150 trillion dollars in minerals locked up in the Western states.” That says it all.

It’s unclear whether American conservationists are prepared to counteract the growing threat to public land and environmental law. If the Bundy occupation has any positive impact, it will be raising the profile of the crusaders and their extreme goals. Already, some public land supporters and wildlife enthusiasts are rallying around Malheur. These counter-protestors seem keenly aware of the public trust—the promise of democratic ownership and management—that the refuge represents. They are wise to the broader context.

“There’s a movement right now to roll back natural resource protection, to roll back public ownership of land, and this occupation rips the veneer off of that agenda,” says Bob Sallinger, conservation director at Audubon of Portland and a counter-protest organizer. “People can now see what it looks like on the ground.”

As always, in the perennial struggle for Western lands, it’s “keep it public” versus “private profit.” In Oregon, the “private profit” crowd has shown us the future it hopes to foment.