Walk around any city at dawn this time of year and you’ll likely encounter a grim, feathery graveyard. Migrating birds that have crashed into windows lie stunned or dead at the bases of buildings, only to be swept up by property managers or snatched away by predators as the sun rises.

Collisions with buildings and other human structures are perhaps the biggest contributor to avian fatalities in North America. Many species migrate by night and are perilously dazzled by artificial illumination, for reasons we don’t yet completely understand. Lights on skyscrapers, airports, and stadiums draw birds into urban areas, where they smack into walls and windows or each other, or flap around and eventually perish from exhaustion-related complications.

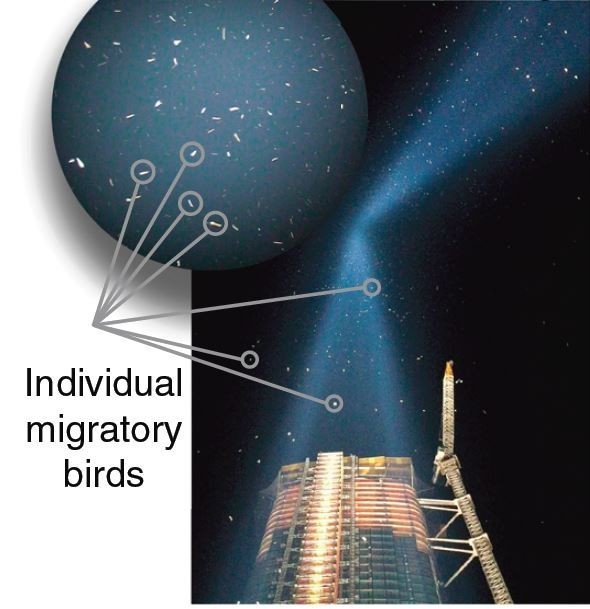

We now have a comprehensive and weirdly fascinating case study of this problem thanks to researchers probing some of America’s most-famous artificial lights—the night-burning beams paying tribute to the September 11th attacks each year at New York’s former Twin Towers site. Using radar, binoculars, and acoustic monitoring, observers logged a thick frenzy of seemingly lost birds around these lights.

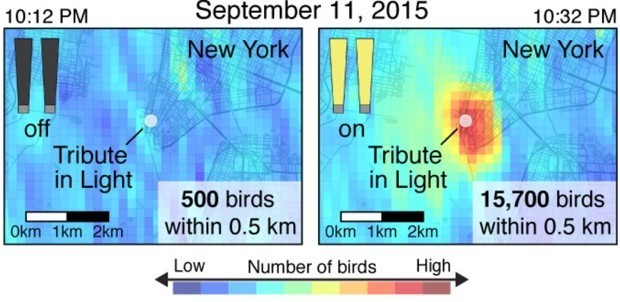

Over seven night-long 9/11 tributes in recent years, the beams disrupted the flight patterns of more than a million birds, causing them to aimlessly loop and chirp incessantly, according to researchers from the University of Oxford, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, and the New York City Audubon. Nearly 16,000 birds circled the beams over the course of one night in 2015. When the lights were darkened, that number dropped to about 500.

(Graphic: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences)

What’s going on in birds’ brains that makes them react this way? Many ornithologists think it’s related to how the creatures navigate. During migrations in the spring and fall, a large number of species chart their courses according to the position of the setting sun, the moon, and the stars. Glaring lights from human sources short-circuits this system.

“Light is a powerful stimulus. Think of how powerful it can be for attracting moths, or people if you are in a dark place or a place in which some striking light installation points high into the sky above the ocean of artificial light below in a city,” says Andrew Farnsworth, a Cornell University researcher and study co-author. “Also think of what happens when you get very close to such a powerfully intense light—it can become disorienting to perceive much beyond the bright. It seems plausible, without ascribing human traits to birds here, that there may be similar sorts of experiences that attract and disorient birds.”

Birds also have “light-mediated molecules” in their eyeballs that help them detect the Earth’s magnetic field and travel accordingly, which is something light might disrupt, Farnsworth says. “Birds slow to look, or because they cannot see beyond it, they circle trying to gather information about where they are, and they start calling probably as a function of this disorientation to try to locate other individuals like or sort of like them.”

(Graphic: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences)

Observers noted flight disruptions of as many as 2.5 miles as a consequence of the 9/11 beams, particularly in warbler species like the American Redstart, Northern Parula, Ovenbird, and Common Yellowthroat, as well as with Baltimore Orioles and Yellow-billed Cuckoos. So how can humans pry these creatures from the perilous magnetism of the tribute beams in New York, where an estimated 90,000 birds die from building collisions each year?

Well, some plans are already in motion: Several years ago, the tribute organizers started shutting down the installation for 20 minutes if they noticed more than a thousand birds circling dangerously. That action helps “avoid a pile of dead birds in southern Manhattan,” says Farnsworth, and shows that “despite the charged and emotional and somber energy of the tribute … [the organizers] care about birds as well.”

“Any bright light or sets of bright lights can interfere with migration at night,” Farnsworth adds. Lit-up energy infrastructure can be a culprit, too, including in rural areas. New York is also one of several North American cities, including Chicago, San Francisco, and Toronto, with a “lights-out” policy, dimming illumination during migrating seasons in towers like the Chrysler Building and Rockefeller Center.

Even so, many bird-lovers would argue more should be done in New York and beyond, like making other imposing structures dark at night and designing artificial lights to point downward instead of at the sky. “The best solution is absolutely to turn off lights where and when possible,” Farnsworth adds. “If we can mitigate our behavior—and this is in the grand sense—so that our actions don’t cause more death, that’s a good thing.”

This story originally appeared on CityLab, an editorial partner site. Subscribe to CityLab’s newsletters and follow CityLab on Facebook and Twitter.