A rising tide does not lift all boats, but it certainly sinks some faster than others.

We’ve known for a long time that developing countries are the first to bear the effects of climate change, and the least equipped to recover. Yesterday, the World Bank issued some thorough and sobering numbers about the new global poverty that we can expect over the next 15 years, as climate destruction in those countries drives up the price of food and medical care, threatens basic infrastructure, and accelerates the transmission of “climate-related diseases” such as malaria. There’s time for us to change these numbers, but that time is dwindling.

“In the short run, rapid, inclusive, and climate-informed development can prevent most (but not all) consequences of climate change on poverty,” the authors of the report write. “Absent such good development, climate change could result in an additional 100 million people living in extreme poverty by 2030.”

It becomes clearer each day that the cost of developing the first world has been levied on the third.

The report, which draws on household surveys from 92 countries, differs from earlier, related efforts “by looking at the poverty impacts of climate change at the household level, rather than at the level of national economies.” This more granular approach to data-gathering enables convincing projections: Sub-Saharan Africa, for example, is set to see food prices rise 12 percent by 2030, barring major mitigation efforts with the full backing of the first world. Those that benefit least from global warming suffer the most.

The World Bank’s projections for food scarcity offer four possible paths: no climate change (too late for that), low emissions (we’re not there yet), high emissions, and high emissions without CO2 fertilization. Here’s what those four projections look like in Africa and Asia:

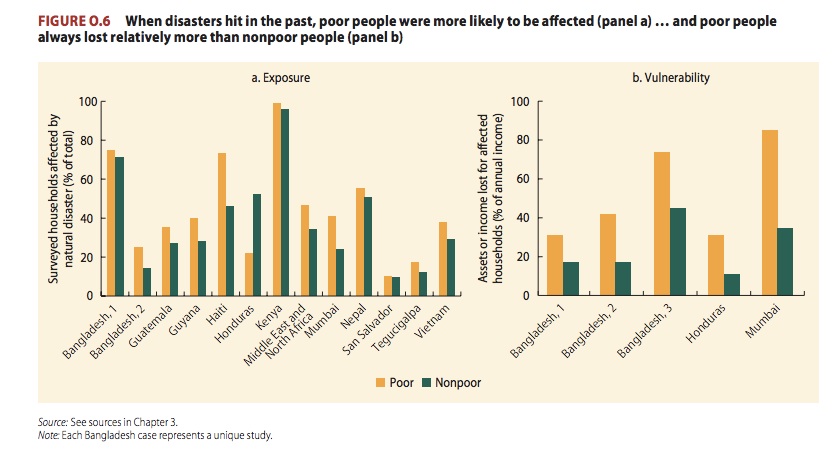

As for who gets hit first and hardest during climate instability and natural disasters, it is also poor people:

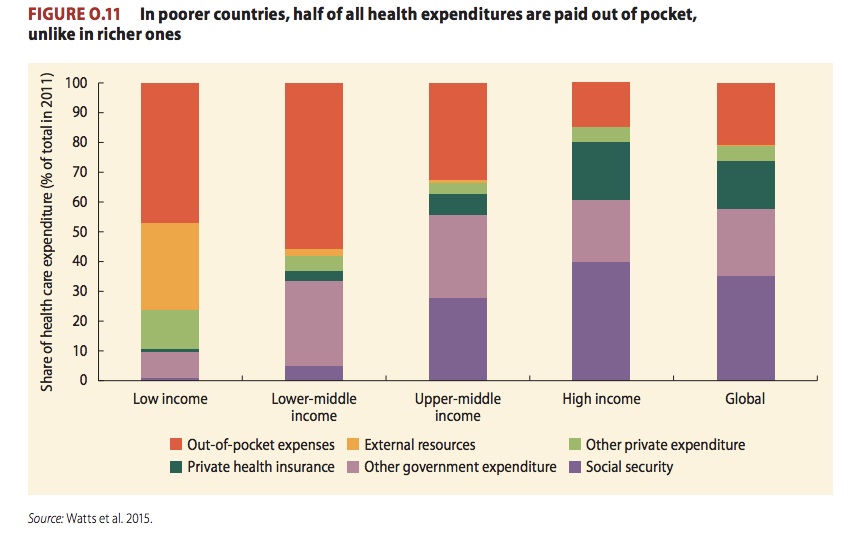

And when it’s time to go to the hospital, it’s in developing countries where you’re most likely to pay out-of-pocket for medical treatment:

This research builds on an earlier 2010 World Bank report, which sought to “establish an agenda for research and action built on an enhanced understanding of the relationship between climate change and the key social dimensions of vulnerability, social justice, and equity.” The new report—200 pages before the index—offers the fruit of that research, and the full weight of that understanding.

As the United Nations COP21 climate summit approaches, a central question is whether the world’s wealthiest countries will arrive prepared to make ambitious commitments to fund mitigation and development in the poorest, most vulnerable countries. Finance ministers from 20 of these at-risk states have banded together under the “V20” banner to make the case that subsidizing climate needs in the developing world is not just a humanitarian question, but one of self-interest even in the first world; speaking in September in the Philippines, World Bank Vice President and Special Envoy for Climate Change Rachel Kyte noted that developed countries save roughly four dollars in relief efforts for every one dollar we spend on work to mitigate the impact of extreme weather.

That money is starting to come in: Last month, at a meeting of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank in Peru, the Bank pledged to boost financial assistance to poorer nations above its previous projections, while the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change is seeking a global commitment of $100 billion a year by 2030.

In a recent op-ed in Time magazine, former President George W. Bush reflected on his legacy in Africa: “Saving lives in Africa serves America’s strategic interests,” he wrote. “When societies abroad are healthier and more prosperous, they are more stable and secure. They become markets for our producers.” We’re beginning to recognize the limitations of market-based humanitarianism. There will be zero foreign markets for American producers unless we take radical action to preserve the most basic elements of our ecology, and to preserve our less-fortunate neighbors. But it’s also dangerously backwards to talk about preserving markets for “our” goods, when it becomes clearer each day that the cost of developing the first world has been levied on the third.

“Catastrophic Consequences of Climate Change” is Pacific Standard’s aggressive, year-long investigation into the devastating effects of climate change—and how scholars, legislators, and citizen-activists can help stave off its most dire consequences.