As residents in North Carolina recover from the massive flooding brought on by Hurricane Florence, they’re getting inundated by another unwelcome visitor. Swarms of them: In one video taken recently, a mother contemplates how to get her and her child out of a car surrounded by what appear to be wasps. Dozens cling on to their windows.

“They’re not wasps, baby, they’re mosquitoes,” the woman says when her child asks about them.

Spikes in bloodthirsty mosquito populations are common after major storms. And with climate change bringing more storms like Florence, and also upping their strength, the increased potential for the transmission of vector-born illnesses like Zika, West Nile, and the chikungunya virus are a top concern for public-health experts.

“That’s one of the hottest topics in climate and health right now,” said Juanita Constible, a climate expert at the Natural Resources Defense Council. “And that’s partly because the answer is so dependent on the mosquito and disease in question, and where the mosquito and [pathogen] live.”

The good news is that, despite their monstrous size and painful bites, the breed that’s overrunning North Carolina—called Psorophora ciliata, or gallinippers—are known predominantly as nuisance mosquitoes. “Those are not the kind that transmit pathogens causing disease in people,” said Chris Barker, an expert of mosquito-borne viruses at the University of California–Davis. “These are often floodwater species whose eggs are in the soil when the hurricane arrives.” The eggs stay dormant near ponds, streams, and other bodies of water. When those areas flood, they hatch en masse.

Speaking to USA Today, entomologist Michael Reiskind at North Carolina State University said he counted just three such mosquitoes in five minutes before Hurricane Florence hit. A week after the storm, he counted eight in the same time span, and, two weeks later, a whopping 50. So they are a public-health concern as they hamper recovery efforts; to combat them, North Carolina Governor Roy Cooper ordered $4 million in funding last week toward mosquito control in the areas hardest hit by the hurricane.

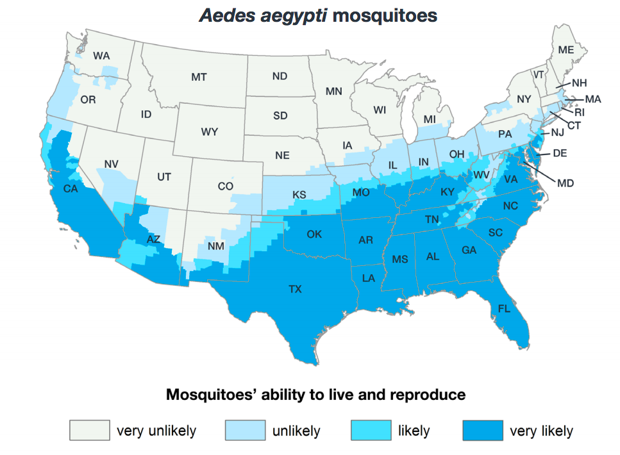

(Map: CityLab/The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

That brings us to the other kinds of mosquitoes—the ones that are capable of transmitting diseases to humans. The jury is still out about how exactly climate change will affect their spread, but public-health officials aren’t taking any chances. After Hurricane Harvey last year, the United States Air Force was called in to help spray coastal regions of Texas to combat potential booms in Culex and Aedes mosquito populations, which can carry the West Nile and Zika viruses, respectively. Both diseases are endemic to the region.

And the threat of dengue and Zika-carrying mosquitoes loomed large over Puerto Rico in the months that followed Hurricanes Maria and Irma, which created the perfect conditions for an outbreak: pockets of standing water, stifling heat and humidity, power outages, and a general skepticism over aerial spraying of insecticide.

Unlike the nuisance mosquitoes, these breeds don’t populate during the flooding. In fact, they initially get flushed out of the urban water system by the storm. But they can come back in full force weeks, months, even years after a storm if recovery efforts fall short.

Case in point: A 2008 study by researchers at Tulane University found that, in parts of Mississippi and Louisiana, cases of West Nile virus reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention more than doubled a year after Hurricane Katrina hit. Though the researchers stopped short of directly blaming the hurricane, they suggested that the uptick may have been a result of increased breeding grounds from fallen trees and stagnant water on abandoned property.

Barker says timing is everything. “An early hurricane would have a much greater potential to increase disease risk in the continental U.S. than a hurricane that occurs in late September early October,” he said. “At that point, the weather’s cooling pretty rapidly, and mosquito developing times and the incubation period of the pathogens get longer.”

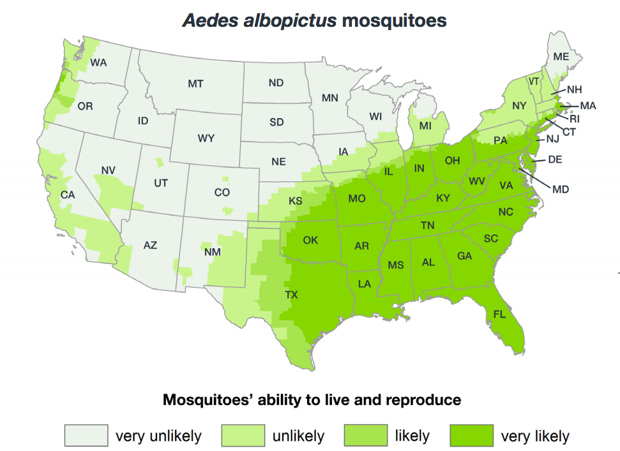

(Map: CityLab/The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

That points to one of climate change’s most prominent effects on the spread of vector-borne illnesses: rising temperatures that make seasons warmer. That can then expand the niche habitat of disease-carrying mosquitoes (and ticks)—often farther north—and even speed up the incubation period for that pathogen.

“That extension of habitat is a combination of climate change and human behavior,” Constible said. “Urbanization can expand habitats for some species of mosquito that prefer cities, so as people expand into natural areas, those species will go with them.” Not only do urban settings have plenty of habitat and food, but, in cities, mosquitoes lack natural predators.

In the U.S. currently, the proliferation of the disease-carrying Asian tiger mosquito and their Aedes aegypti cousins, both of which thrive in cities, remain one of the main targets of researchers like Barker. “Right now in California, we’re dealing a lot with invasive mosquitoes that aren’t thought to be here around 2000,” he said. “In 2011, the Asian tiger mosquito was found in the Los Angeles area, and, in 2013, we also discovered Aedes aegypti in the Central Valley and in the San Francisco Bay Area. Since that time, those two mosquito species have continued to spread.” Though, he reminds us, their spread can’t be pinned to climate change alone. Tourism, globalization, and the migration of animals all play a role too.

So what does that mean for cities? Researchers are constantly coming up with new weapons, however controversial they may be, like genetic mutation and even artificial intelligence. Constible says most cities, though, aren’t doing enough. Too many are reacting to influxes of mosquitoes—via spraying campaigns, for example—and not enough are being proactive.

That means having a climate adaptation plan, and making mosquito-borne illnesses one of the top priorities of that plan. That also means conducting more vigilant surveillance of where mosquitoes are showing up across the nation, lest cities get caught off guard.

This story originally appeared on CityLab, an editorial partner site. Subscribe to CityLab’s newsletters and follow CityLab on Facebook and Twitter.