It’s easy to dwell on the many ways that climate change is disrupting our communities as we try to just stay put. Amped storms can tear up homes; droughts can parch farms; and floods can inundate schools and hospitals.

But what about when we’re moving around—say, on our daily commute, or when we’re flying from one coast to another? Could we shake the effects of extreme weather and rising seas if we just hurtle around the nation at full throttle, shifting from flooded areas to dry ones?

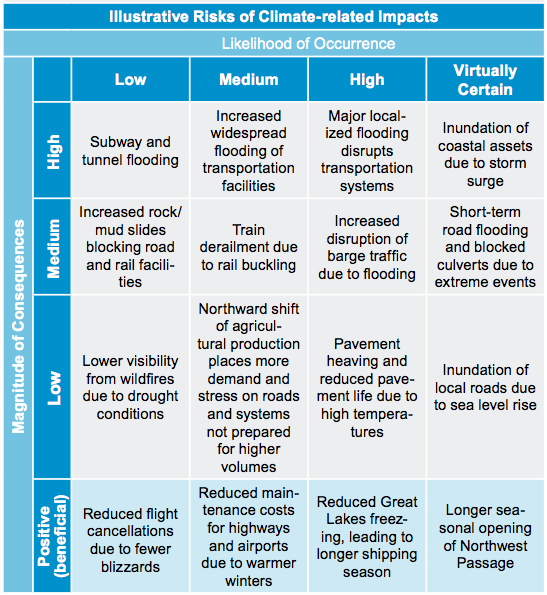

The Obama Administration published a hefty national climate assessment this week, and it devoted a chapter to climate change’s impacts on transportation networks. The conclusions in that chapter were about as pretty as bacteria-riddled seats aboard a diesel-burning bus. They were reminders that America’s $4 trillion worth of transportation infrastructure is vulnerable to the meteorological ravages of a warming world.

You can’t outdrive a storm on a flooded highway, and you can’t jet away after a storm if airport runways are flooded.

“Delays caused by severe storms disrupt almost all types of transportation,” the chapter states. “Storm drainage systems for highways, tunnels, airports, and city streets could prove inadequate, resulting in localized flooding. Bridge piers are subject to scour as runoff increases stream and river flows, potentially weakening bridge foundations. Severe storms will disrupt highway traffic, leading to more accidents and delays. More airline traffic will be delayed or canceled.”

(Chart: National Climate Assessment)

These aren’t far-off threats—they’re already happening. Millions of New Yorkers were unable to ride the Subway for at least a week in 2012 after the network was flooded by Superstorm Sandy, which scientists have linked to climate change. The three main airports serving New York City flooded. Ships ran aground. More than 200,000 parked vehicles were damaged.

And knocking out a road, an airport, or a railway, the report reminds us, “can have ripple effects across a network, with trunk (main) lines and hubs having the most widespread impacts.”

Planning ahead is our best option for managing climate change’s impacts on our transportation networks. (And shifting rapidly to the use of electric vehicles that plug into grids that are free of fossil fuel power would reduce transportation’s impacts on the climate.)

“Our chapter was designed to focus transportation planners on what they should consider,” says Michael Kuby, a professor at Arizona State University’s School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning and one of the lead authors of the chapter. “It’s fairly clear that planners are still in the early stages of incorporating climate change into their planning, and that the response varies from region to region.”

And for those planners, Kuby has some advice. “We have to think of our transportation system as an intermodal network system,” he says. “One of the best forms of resilience is to be able to reroute traffic to other parts of the network or to other modes in the event of temporary or permanent shutdown.”