Computers can kick our butts at math, logic, and chess—by now, that’s a given. But reading emotions, most of us probably would like to believe, is a skill reserved for humans. Isn’t that a big part of what separates us from machines in the first place?

Well, not anymore. In a study published this week in Current Biology, researchers led by the University of California-San Diego’s Marian Bartlett pitted humans against computers in a battle to see who could best distinguish between genuine and faked facial expressions of pain. We lost, by a lot.

In the experiment, more than 150 participants were shown short videos of the faces of people who either dunked their arms in ice water or pretended to dunk their arms in ice water. The group was asked to gauge the authenticity of each pained reaction, and succeeded in weeding out the fakers from the true sufferers only 51.9 percent of the time—no more accurate than if they simply had left their guess to chance.

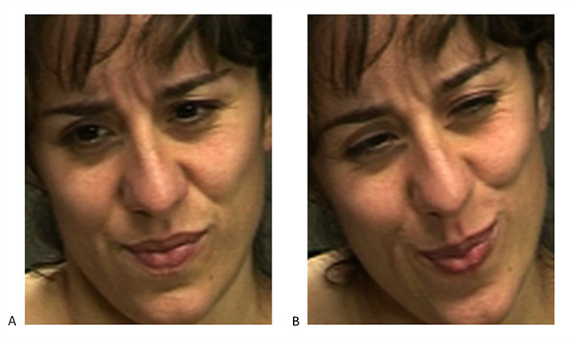

Which video screenshot shows this woman experiencing actual pain? (Photo: University of California-San Diego) (Answer: B)

Next, the researchers showed the same videos to computers with special expression recognition software. The computers’ accuracy? Eighty-five percent.

That the humans performed so poorly actually is no surprise. Scientists have known for a while that even trained physicians can’t reliably differentiate between real and faked pain expressions.

But the computers’ results were unprecedented. Bartlett and her colleagues call the success of the recognition software “a significant milestone for machine vision systems.” While computers’ logical prowess has been demonstrated for decades, the machines “have significantly underperformed compared to humans at perceptual processes, rarely reaching even the level of a human child.”

The secret to computers’ improvement, the researchers explain, is their newly refined ability to exploit one of our own physiological quirks. Two distinct motor pathways control our facial movements, one for the expressions we choose to make and the other for expressions we make spontaneously in reaction to something. When we attempt to mimic an emotion like pain, the former pathway directs our features based on what it estimates that emotion is supposed to look like, without any definitive blueprint to follow. Inevitably, small differences crop up that are too subtle for the naked eye, but not the digital lens.

“The single most predictive feature of falsified expressions of pain is the dynamics of the mouth opening,” which alone can account for 72 percent of the accuracy, the researchers write.

It’s not hard to spin the computers’ emotional savviness as a harbinger of machine domination, but Bartlett and her colleagues prefer to look at more practical applications. These include preventing insurance fraud by catching patients who lie to their doctors, improving homeland security, and exposing students who only pretend to pay attention in class.

Heightened surveillance of our expressions could have big costs, too, of course. The software, like many new technologies, leaves us with a big question: How much do we really want computers to know?