As Tropical Storm Harvey continues to pummel an already devastated Houston, many residents are terrified that the dams on two of the region’s massive reservoirs will fail, releasing a torrent of water into portions of the city that are already submerged—including downtown.

The extra water that has accumulated in the Addicks and Barker reservoirs has strained their earthen dams—which have been considered in critical condition for several years in large part because of how ruinous it would be if they failed.

But the United States Army Corps of Engineers says that, despite the fears, the dams are not in danger of failing. Here’s why:

What are the Addicks and Barker reservoirs?

The two reservoirs, built by the federal government in the 1940s, were meant to hold excess rainwater to protect Houston from catastrophic flooding. The idea was that, when heavy rain fell, Addicks and Barker could catch it before it flowed down Buffalo Bayou into west and downtown Houston.

Is water going to overtop their dams?

No, says Richard Long, who oversees the operation of the reservoirs for the Army Corps. He said Tuesday that “the dams are designed not to be overtopped through the use of auxiliary spillways.” These spillways are located well below the top of the actual dams in each reservoir; excess water in the reservoirs will go over these auxiliary spillways long before it would reach the top of the dams.

As of now, the Army Corps says there’s enough excess water in the Addicks Reservoir that some of it is flowing around (not overtopping) one of the auxiliary spillways. The agency originally thought water might also have to flow around the spillways for Barker Reservoir, but now projects that will not be necessary as long as the weather stays good.

All this is still a very big deal—the Army Corps has never had to resort to it before. But it’s not the catastrophic situation for downstream neighborhoods that many perceive it to be.

Why are the spillways a big deal? And what will the impacts of using them be?

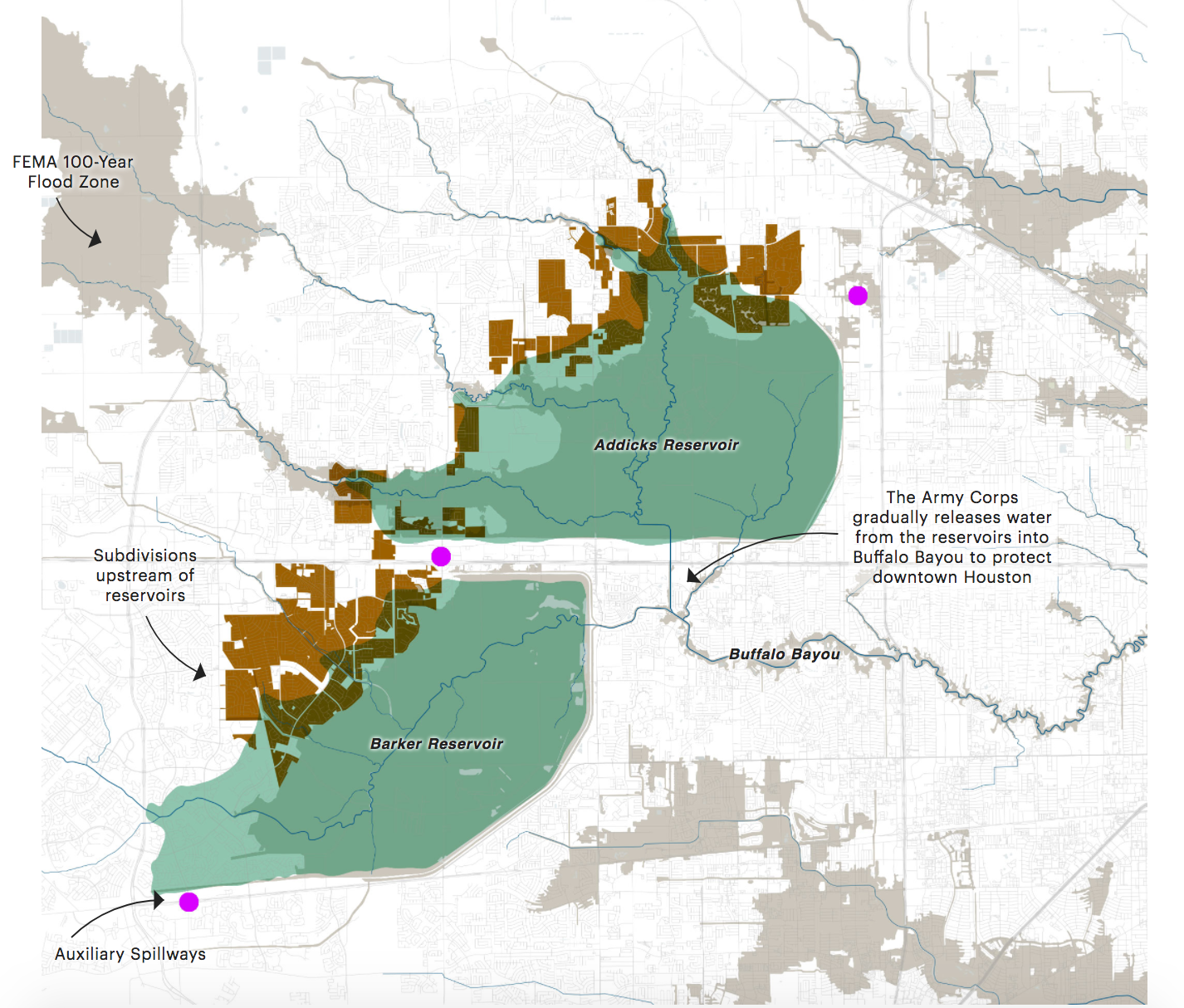

The water that goes around the auxiliary spillway of Addicks Reservoir is going to have to leave the reservoir somehow—and enter areas surrounding it. The Army Corps can’t say exactly what areas might experience additional flooding, but local officials did say to expect more water to flow into the vicinity of the spillway on the northwest side of Addicks. This week, Harris County Flood Control District listed 53 subdivisions in the Addicks watershed and 40 in the Barker watershed (shown in brown in the map above) at high risk of flooding.

Jeremy Justice, a hydrologic analyst at the Harris County Flood Control District, said two subdivisions near the Addicks reservoir—Twin Lakes and Lakes on Eldridge—are particularly vulnerable to flooding from the Addicks spillway. Those homes “probably should never have been put there,” he said.

So why are homes surrounding the reservoirs already flooding?

Thousands of homes and structures surrounding the reservoirs have indeed already flooded. Some of them are flooding because they’re along creeks and bayous that have also been overwhelmed. Some are flooding because of bad drainage in the neighborhood. But many are flooding because they are in an area that the Army Corps actually considers to be inside the reservoirs.

The Army Corps says that as water goes around the auxiliary spillway of Addicks Reservoir, the flooding close to the reservoirs may get worse for homes that have already been impacted. But officials don’t yet know how much worse.

Why is the Army Corps also releasing water from the reservoirs down Buffalo Bayou? Weren’t the reservoirs built to help avoid that?

There is so much rain falling in the area right now and the reservoirs are under so much stress that the Army Corps is faced with a tough balancing act.

Addicks and Barker were originally built solely to protect against flooding in Buffalo Bayou that would impact west and downtown Houston. The Army Corps built them in the 1940s in an area that was pretty much totally undeveloped. The agency had hoped to buy even more land to build the reservoirs on, plus extra land as an additional buffer, but that never happened.

For decades, that wasn’t a huge deal. If the reservoirs filled up with rain and areas around them flooded, no one lived there. But today, many people live right around the reservoirs. That creates two problems.

First, the Army Corps now has to worry about flooding neighborhoods surrounding its reservoirs. Second, all those neighborhoods have added a lot of non-absorbent concrete to what was once water-absorbing green space—so when rain falls into the area, less of it is absorbed by the ground. That means more of it ends up in the reservoirs than it used to.

The Army Corps must now protect neighborhoods both upstream of the reservoirs and downstream of the reservoirs. In order to prevent catastrophic flooding upstream of Addicks and Barker, the agency has been releasing what it says are small amounts of water down Buffalo Bayou. This balancing act will continue, and it’s already created a huge political headache for the Army Corps.

Last year, well before Harvey, Long described the Army Corps as “between a rock and a hard place.”

Why are homes so close to the reservoirs?

Good question. Because local officials let it happen.

Could the dams for Addicks and Barker ever fail?

The Army Corps tells us the likelihood is minuscule even with this week’s historic rainfall, which has strained their earthen dams. Fear and speculation about the dams’ potential failure has been spurred by their placement several years ago on a list of critical infrastructure. But the Army Corps says they are on that list because of what could happen if they ever did fail—not because they’re actually in danger of failing. If a breach were to occur, the Army Corps estimates it would cause $60 billion in damage and more than one million residents downstream would be impacted.

This post originally appeared on ProPublica as “Houston’s Big Dams Won’t Fail. But Many Neighborhoods Will Have to Be Flooded to Save Them” and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.