In northern Indiana, an exceptionally flat part of the Midwest that even midwesterners love to hate, Interstate 65 stretches as far as the eye can see—and then some. For a 170-mile radius, you pass little but cornfields, semi-trucks, and the occasional cow. Then, from the empty horizon, a cluster of red roofs emerges like an irate Goliath. Right off the highway—at the exit urging you to “mooove over!”—lies an “agricultural Disneyland.” Make that turn and you’ll arrive at Fair Oaks Farms, a sprawling agricultural theme park—and, yes, a bit like Disneyland, if Disneyland were sadder and grayer.

Dairy Disneyland: One Farm’s Quest to Save Industrial Agriculture, by Emily Moon. Listen to more Pacific Standard stories, read out loud.

A sign at the farm’s entrance marks the next of many puns, seemingly mandated by company code: “A Dairy Good Time for the Family!” Inside the barn, a group of employees, all wearing matching polo shirts, speak in dairy puns as they herd schoolchildren on cow-shaped busses and dairy-go-rounds, and invite the many dozens of visitors from across the country to take the Dairy Adventure. (There’s a pig- or crop-themed tour too, if that’s more your thing.)

Monopolizing the small, unincorporated town of Fair Oaks, Indiana, this working industrial farm manages to both produce most of the Midwest’s milk and welcome thousands of tourists a year into its glass-walled operation. On a Friday in May, there are 450 people scheduled to partake in the “adventures,” a crowd that the front desk people characterize as a “slow day.” The museum and admission buildings, painted a pristine red, look like a toy farm set: the kind of thing you could order from a Fisher-Price catalogue. Everywhere there are monuments to dairy—cow statues painted with the Indiana state flag, a giant milk bottle—but there are no real animals and no exposed earth.

(Photo: Kelly Tan/Pacific Standard)

It’s hard to overstate how removed Fair Oaks feels. The closest city is 10 miles away—Rensselaer, population 6,000. This is the area that locals call “the region”: on the same time zone as Chicago, but an hour (and seemingly worlds) away, with squat, paint-chipped houses accessible only by a frontage road.

But no matter—Fair Oaks Farms has everything you could ever want. There’s a gas station, a cafe (“Cowfe“), and the Farmhouse Restaurant, which serves pork burgers and cheese made from Fair Oaks’ own animals. A giant, red, barn-shaped Marriott opened near the farm in January, with a water park soon to come. Jamie Miller, general manager of attractions at Fair Oaks, has high hopes for the hotel: conventions, families, bridal parties. “We hope to be the agricultural hub for the United States,” she says.

To see what the animals look like before they become burgers, you board the bus to a large-scale dairy and pig farm, both modeled after the co-op’s real operations, which are located off-site. On the dairy side, employees guide you through a feeding operation, a top-of-the-line manure recycling system, free-stall barns, and a milking parlor. As the tour bus blazes past amber fields where corn is grown for feed, a cool, male voice emanates from the speaker above and declares with movie-trailer gravitas, “The fabulous dairy cow converts all this feed into the most wholesome food on Earth: milk.”

Fair Oaks is certainly the kind of place that invites hyperbole. The chefs load their deluxe grilled cheese with thick slices of Swiss, cheddar, and Havarti. There’s at least one giant milk bottle that doubles as a rock-climbing wall, jutting out of the ground like an obelisk that belongs in some great capital city. I lost count of the cow statues.

And, of course, the operation itself is big—only 1 percent of U.S. dairies have 2,500 cows or more, and Fair Oaks has 36,000. Its founders have earned the Disneyland moniker for a reason: Within the frequently maligned business of industrial agriculture, Fair Oaks Farms is the happiest place on Earth. Some activists might say it’s all a façade—a mere marketing ploy—papering over the industry’s history of abuses with some much-needed good press.

One tour guide insists, sincerely, “Milk is the magic.” Still, upon closer look, this wholesome image is rather like the voice in the bus: disembodied, pre-recorded, and, to be honest, a little smug.

The story of Fair Oaks Farms, as its owners tell it (and they tell it often: in TED Talks, on bus tours, in glossy, cow-covered pamphlets), begins with a family of dairy farmers, the McCloskeys. After his Puerto Rican mother moved the family back home, Pittsburgh-born Mike McCloskey spent his childhood roaming the island’s farmlands, riding along with his uncle and cousins in their truck. More than anything, he loved working with the family’s cows and chickens. Mike never lost that passion, and after high school decided to become a large-animal vet—a dream that led him to a veterinary residence at the University of California–Davis. Two years later, he opened his own private practice near San Diego. Already an entrepreneur, Mike’s side hustles at the time included managing rental properties.

On another coast, an ambitious young woman was studying art history in New Jersey. A suburbanite, Sue McCloskey had never set foot on a farm. But after moving to California, she soon fell in love with her landlord—or as she describes him, her “hot milk man”—Mike. “Very quickly I became swept up in all things dairy,” she told a California crowd in 2018.

Branching out from Mike’s veterinary practice, the new couple started their own farm in 1984 with just 300 cows, which they called “their girls,” working their way up to a 5,000-cow farm in New Mexico. Mike was deeply driven. Maybe a little too much. After he joined a large co-op out of a desire for financial protection, he realized he’d been roped into a scam—cutting high-quality milk with the mediocre stuff—and, at meetings, he urged the co-op leaders to use better methods, as Mike later said in an interview with National Public Radio. As their relationship with the co-op soured, the McCloskeys split off from what they now call the “dairy establishment” to start Fair Oaks Farms. From here, their mythos skews toward something like a traditional start-up origin story: They drew up plans for their own co-op at the kitchen table. With a map of their property spread out before them, the McCloskeys circled prospective buyers and processors, who soon became customers and collaborators. They joined forces with nine other farmers to found Select Milk Producers, Inc., now the sixth-largest dairy co-op in the country, producing about $2 billion in dairy products each year.

(Photo: Kelly Tan/Pacific Standard)

After expanding in the late 1990s, Select Milk brought in Gary Corbett, a high-level executive from dairy giant Dean Foods, to run the farm’s operation as chief executive officer in a land of dairy and promise: northwest Indiana. Beginning to notice a new threat, they figured they needed help. Animal rights activists had grown bolder. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals and the Humane Society of the United States regularly broadcast graphic images of bruised and beaten farm animals, high-profile undercover investigations turned up abuses and public-safety hazards, and boycotts drove farmers to bankruptcy (and others to jail).

Mike and Sue had not yet become a target, but they’d seen similarly sized operations go down. Hemorrhaging money and lobbying for ag-gag laws, which criminalized undercover investigations of agriculture operations, some producers retreated from view. The McCloskeys, however, did not want to hide. Instead, Select Milk commissioned a white paper on potential risks from “anti-agriculture” activists, which found “these groups tend to be very committed to their cause, very articulate, very well funded, and passionate,” says Corbett, who calls himself one of Fair Oaks’ “founding fathers.” Because of this passion, producers had already suffered through the largest meat recall in U.S. history.

With fewer farms and fewer farmers to sway consumers toward their side, the co-op worried that city folks, whom Corbett calls their “urban brethren,” could fall prey to PETA’s messaging. “Our initial reaction was that we’ve got to go on the offense,” Corbett says. There was only one solution: Win the public over before it could turn on them. Prominent reformers in the industry, like celebrated animal scientist Temple Grandin, had already suggested that farms turn the metaphorical “high walls of industrial agriculture” into glass. Why not be literal about it? “We thought maybe the best credibility builder is if we invite people into our home,” Corbett says.

The founders began to design a tour that would allow visitors to physically walk through their workplace—behind biosecure panes of glass. They updated their practices in anticipation of pushback: quitting tail-docking, and, later, setting up a revolutionary recycling system to convert manure into fuel. They visited nearby museums, consulted with an ad agency, and reached out to Indiana’s branch of the national dairy checkoff, a semi-public organization that promotes dairy products through research and marketing, and is funded through a government-mandated tax on producers. With the help of the checkoff and the many farmers who pay for it, the McCloskeys’ vision had the potential to become the next great dairy marketing campaign, on par with “Got Milk?”

Together, the founders decided the attractions would focus on three main messages: Agriculture is good for the environment, it’s compatible with animal welfare, and milk is good for you. The experience had to be appropriate for kids, but also for parents—and for any unwitting driver off the interstate. It had to be educational, but entertaining; universal, but representative. Most Americans only interact with agriculture in the grocery store, or at farmer’s markets, if they’re into that sort of thing. But this—this would be an adventure. It seems that subtlety, however, was not one of their directives: Today every surface, from the cow-print booths in the gift shop to the dairy-go-round in the museum, screams “MILK.”

At the time, this level of transparency was unheard of. “Farmers and ranchers adopted a kind of bunker mentality,” explains agriculture lobbyist Steve Kopperud. Anyone who had contemplated agritourism decided, “It’s too bad, we’d like to, but it’s not worth the risk.” Although lobbyists, economists, and producers all agreed agribusiness had an image problem, no one was willing to solve it.

(Photo: Kelly Tan/Pacific Standard)

“Pork has got a bad name,” one Fair Oaks tour guide told me. “Since biblical times, right?” Or, as Corbett puts it, “The problem was, when the world changed and consumers had questions, agriculture didn’t have a history of answering them.”

The new chief executive officer also had his doubts. Sitting in a pick-up truck with the president of the state’s Dairy Education Center in 2000, he wondered: Could they pull this off? Or were they just asking for trouble? In the end, “it wasn’t a question of whether we could afford to do this,” he says. “It was a question of whether we could afford not to do it. It ain’t Iowa and it ain’t heaven. Build it, and maybe they won’t come.”

But they did come. In 2004, the farm opened the Dairy Adventure, a non-profit centered around a tour of a commercially viable, working dairy farm. While other producers were embroiled in messy fights over ag-gag laws and toxic waste, Fair Oaks earned the praise of Hoosier mommy blogs, trade magazines, and local media. At conferences, farmers spoke of Fair Oaks in exalted tones. Even PETA put out a statement praising the farm’s decision to phase out dehorning, a painful industry practice.

All this positive press drew the attention of another, less wholesome industry. If any commodity needed a makeover, it was pork. At their peers’ urging, Belstra Milling Co., an Indiana-based feed company that owned several hog farms nearby, agreed to go in with Fair Oaks on a new venture. The McCloskeys built a working pig farm modeled after Belstra’s on their own property, and, in 2015, the two companies unveiled the Pig Adventure, marking the occasion with the greatest party northwest Indiana has seen this side of Gary. Kevin Bacon headlined the Grand Opening with his band, the Bacon Brothers; then-Governor Mike Pence was also in attendance when the Crop Adventure, sponsored by Land O’Lakes, Inc., followed in 2016.

Now, Corbett says the co-op is in talks with the poultry industry, and an apple orchard is already on its way. All across the country, as commodity prices fall and bankruptcies soar, farmers are closing their doors. Meanwhile, Fair Oaks can’t stop opening them.

Their production is thriving too. Spread over 32,000 acres and 11 sites, the co-op is now one of the largest dairy operations in the country, with clients like Kroger and Coca-Cola. By 2015, the owners had also settled the decades-long debate over whether consumer concerns matter. A Purdue University study, commissioned by Fair Oaks and its funders, found that people who went on one of the farm adventures were not only more likely to feel positively about agriculture in general, they were also more likely to buy dairy products. “A home run,” Corbett says. (Take that, Iowa.)

Other producers have noticed: In recent years, they’ve started contacting the farm and the checkoff, asking for advice in replicating Fair Oaks’ glass wall strategy. “We’ve found, and others in agriculture are finding, if you’re not willing to tell the story, somebody is going to step up and tell it for you,” Corbett says.

But when you open the doors to everyone, you also invite controversy. Animal rights activists frequently target the farm online, describing the tours with disgust. More than anything, they hate the pretense and the spectacle: family friendly, family run. “Adventure or abomination?” one blogger asked in 2018.

As a country, we’ve grown accustomed to ignoring the messier realities of industrial food production. But when bad actors are forced into the spotlight—by angry activists or undercover videos—the public expects them to be contrite. Fair Oaks Farms, on the other hand, has a holier-than-thou confidence that many animal activists—and even conscious consumers of meat—might find unseemly. For those who oppose animal agriculture on principle, the “Adventures” make a game out of a brutal reality. Its exhibits are at once flashy and pastoral—and aggressively cheesy (a milk-carton scene come to life)—all of which makes it a prime target for sardonic retaliation. In 2014, a vegan living in northwestern Indiana contacted the national advocacy group Farm Sanctuary for help in protesting Fair Oaks along the interstate. The resulting billboard features a pig in a woman’s embrace and the words “friends, not food,” creating an eerily cheerful effect, not unlike the theme park she so despises.

Corporate animal agriculture scholar Jan Dutkiewicz, who assessed Fair Oaks’ transparency in a 2018 paper, says some of these criticisms are valid. It’s still industry practice to confine pregnant sows in gestation crates, dehorn dairy cows, and castrate animals without using painkillers, all of which is glossed over on the tour.

“Fair Oaks tells this story—We’re this happy, bucolic, red-roof barn tourist center,” he says. “The question of who controls land, who controls labor, who makes money—why is this all increasingly so centralized and owned by ever-fewer, ever-larger companies is an essential part of the story of the American food system, and that’s just not there [in the exhibits].”

(Photo: Kelly Tan/Pacific Standard)

Fair Oaks staff says these online attacks are isolated critiques. They don’t fight back anymore, instead trusting their thousands of fans instead to defend them in the comments sections of various blogs and websites. But it does sometimes seem that Fair Oaks will never win, especially since some of its emulators in the industry do not subscribe to the same animal welfare or environmental standards; industry groups like the North American Meat Institute and the Center for Food Integrity are now doing what the lobbyist Steve Kopperud calls “damage control,” putting out their own filmed tours. Activists say these public relations stunts are heavily sanitized, leading PETA spokesperson Amber Canavan to call them “white-glove tours.” “It’s not giving you the full picture,” she says. This is why Kristina Knapp, co-vice president of the Indiana Animal Rights Alliance, posts frequently about Fair Oaks on her blog. “The way that Fair Oaks presents themselves, it almost normalizes this idea of how we treat animals,” she says.

Denise Miller, a longtime Fair Oaks employee who helps deliver calves in the birthing barn, says it’s sometimes a challenge to be sensitive to these criticisms. Separating a cow from its mother, keeping pigs inside—these are all routine practices on a modern industrial farm, uncontroversial among the dwindling, now-less-than 2 percent of Americans who make their living from production agriculture. When Miller worked on her family’s small, independent hog farm, she never had to deal with activists or justify her work, especially not to urban tourists. Now, when she’s assisting births, something she’s done more than 25,000 times in her life, she has to think about optics.

“You have to make sure that everything looks good, and people don’t perceive it as hurting them for any reason,” she says, nodding to the moaning mother cow, whose delivery will take center stage in this cavernous, operating-theater of a barn. “You have to look compassionate, because if you don’t look compassionate, they think that you’re not, and there are just so many things when you’re dealing with human perception.”

Some activists, while privately applauding the farm’s environmental and animal welfare advances, argue Fair Oaks perpetuates the dangerous idea that industrial agriculture is a humane and a sustainable business that can carry the country through the decades of planetary warming that lie ahead. It’s a hopeful message, but, as climate projections of decreasing crop yields suggest, an unrealistic one.

When I visit the farm in May of 2018, the first stop on my tour is the dairy education center, a dimly lit labyrinth of frozen rustic scenes. If the apocalypse were to hit the country, wiping out the population but somehow leaving swaths of farmland intact, this exhibit would lead future alien anthropologists to conclude, logically, that our civilization must have worshiped milk. There are oddly sexualized animatronic dairy cows, corn statues the size of telephone poles, a talking tree that preaches the importance of sustainability, and interactive play stations that let you try your hand at milking a cow (step one: disinfect). After a few tries, I prepare the cow for milking in under 21 seconds, the average for Fair Oaks’ “experienced milkers.”

Recordings, triggered by sensors as you walk by, bring the plaster and plastic to life. Watching kids play on the cow merry-go-round next to an elaborate display on the many benefits of milk—did you know three glasses a day can give you all the calcium and potassium you need?—I started to lose my appetite. Behind the cheesy puns and the smiling tour guides, something felt vaguely sinister. But that could just have been the bespectacled cow puppet leering down from a grain machine.

The bus to the dairy farm is decorated with black and white spots, so that it resembles a giant, misshapen cow. A third-grade class, all in matching, neon-orange T-shirts, boards outside the museum. I take the front seat next to a chatty kid named Dean, who looks like the cheerful sidekick in a Pixar movie. Dean, at nine years old, is more impressed with the bus’ air conditioning than with the particulars of milk production. Over the hour-long tour, I grow to appreciate his commentary, which at first was very poop-based—but then, so is the farm’s power grid.

Dean’s class is one of the many school groups that tours Fair Oaks every year, providing nearly half the farm’s 600,000 annual visitors. Conventions are also big business; thanks to an arrangement with representatives in Indianapolis, Fair Oaks hosts 50,000 Future Farmers of America each spring. They’ve also welcomed such luminaries as the king of Uganda, country singer Travis Tritt, and the chief executive officer of Coca-Cola, who helped pull a calf, a term for assisting a birth. “We’ve had quite the adventure in the last couple years,” Denise Miller says.

As the bus pulls onto a side road, the disembodied male voice booms over the speakers to overpower the sound of shrieking nine-year-olds: “You’ve all heard of the cornbelt? This is it!” (In case we had somehow missed the miles of cornfields on our way in.) The voice continues to inform us of the farm’s history and daily operations, some of which we now glimpse outside. Passing the baby calves, Dean jolted in his seat and emitted a high-pitch scream. “THEY’RE SO CUTE I WANNA SQUEEZE THEM TO DEATH.”

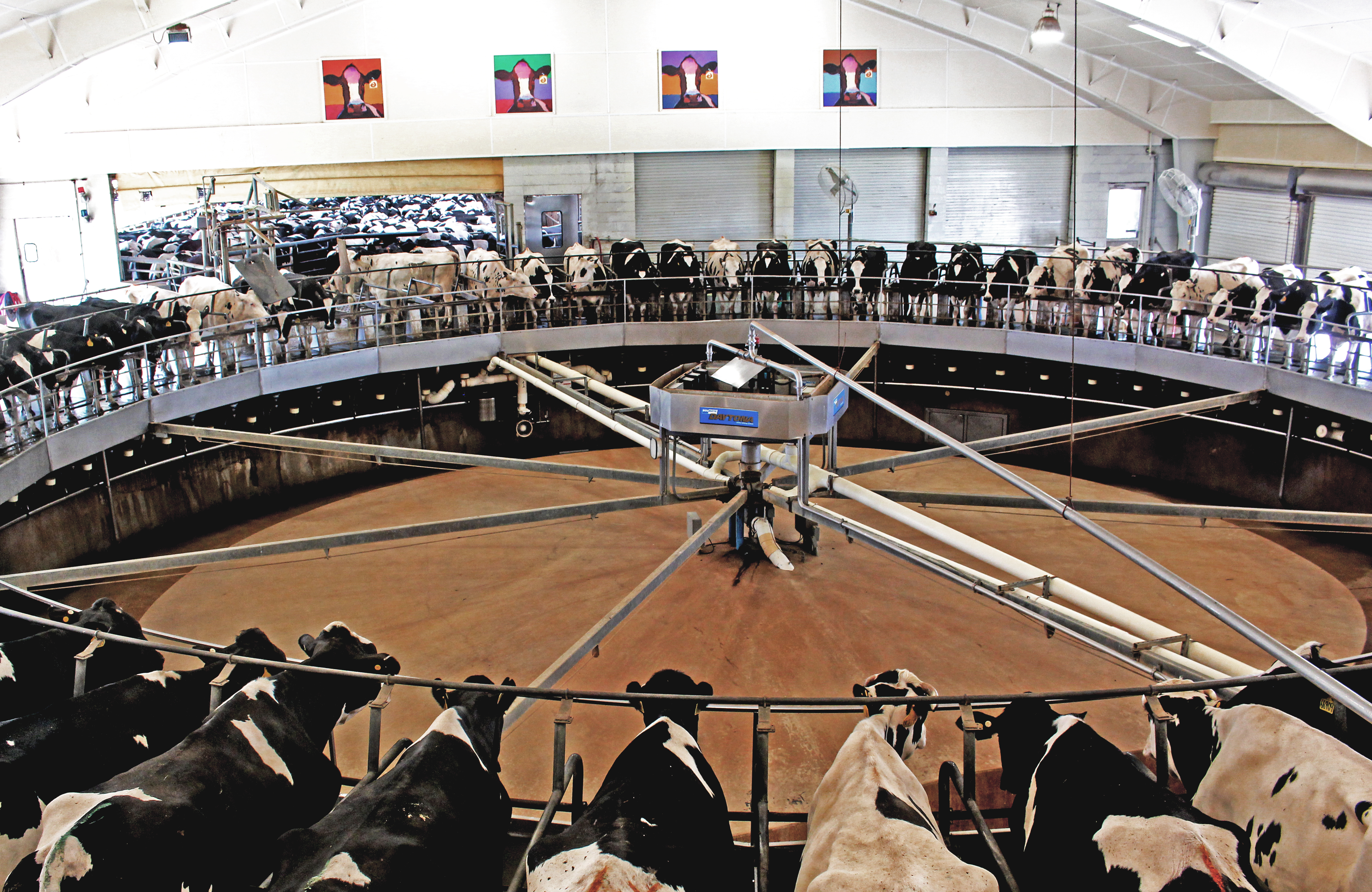

The bus makes a pit stop at the milking parlor, where we climb inside and watch from the window as a machine milks 72 cows on a spinning, circular platform called a rotary. We’re assured that they enjoy the ride. We also learn that Fair Oaks’ co-op produces a total of 250,000 gallons of milk a day, or as our tour guide Paul puts it, “Enough milk for Indianapolis and Chicago.” A lot of it goes to Kroger, the country’s largest supermarket chain. Fair Oaks also makes all of Chick-fil-A’s yogurt, produces the McCloskeys’ patented Fairlife milk, and partners with Coca-Cola to sell Core Power, a flavored, milk-based energy drink that an employee tells me to check out on Amazon.

“What does it feel like to be a cow—does it hurt?” a serious-looking girl asks from the back of the room. Paul looks stumped. After a long pause, he answers: “I wouldn’t know. I’ve never been one.”

Then, remembering his line, he adds, “But I bet it feels dairy fine.”

Paul, who also moonlights as a tour guide in the Crop Adventure, is a retired special education teacher from northwest Indiana. Although he’d never worked on a farm before taking the job, he lights up when explaining Fair Oaks’ newest projects: biotech corn, RFID chips, robotic milkers. Like Paul, most Fair Oaks employees have no prior experience with agriculture. To catch up, they undergo an extensive training process called “Fair Oaks Farms University,” which includes a few days of farm labor. They also study an ever-expanding “playbook” with answers to every question staff has received over the years—and there are stupid questions: Is that a pig? Do you milk the males too? More often, people ask about animal welfare. “We want to speak with one voice so we know we’re giving our consumers the right answers,” Corbett says.

But there are issues Paul doesn’t talk about. Dairy and meat farms contribute almost as much carbon dioxide to the atmosphere as the oil and gas industry, not to mention methane and nitrous oxide, which are even more potent. Animal livestock operations cover one-third of the planet’s land, with more than two-thirds of this devoted to feed crops and much of it recently deforested. One confined animal feeding operation alone produces nearly twice as much untreated waste as the city of Philadelphia, runoff from which pollutes surface and groundwater with excess nutrients, pathogens, and chemicals. The Environmental Protection Agency has found that states with high concentrations of industrial farms experience, on average, 20 to 30 serious water quality problems per year. Consuming more dairy and meat than recommended has been linked to increased risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes, while just living next to a hog farm can raise your risk of asthma. And in January of 2019, a global commission of nutritionists and scientists labeled food production, as it pertains to climate change, obesity, and malnutrition, one of the “gravest threats to human health and survival.”

As the class descends the stairs and re-enters the bus, another tour guide ushers in the next group from the opposite side, repeating the whole Adventure in an endless loop. This time, fifth-graders. Next time, businessmen. The whole thing is perfectly synchronized, the staff members like silent stagehands building the set of a play we never get to see. The rest of the process—slaughter, meat packaging—happens off-site. Fair Oaks staff says this separation is necessary because of biosecurity concerns: Even touching a cow could be dangerous, since farmers and ranchers build up immunities to E. coli and other bacteria that us city folk do not. But it’s also part of a strategy that critics claim is fundamentally anti-activist. Even glass walls can never be fully transparent.