Deforestation rates in southern Africa’s woodlands are five times higher than prior estimates, according to recent research published in early August.

More deforestation, combined with widespread degradation of these savannas, translates to three to six times the loss of carbon as compared to previous estimates, Edward Mitchard and his colleagues write in Nature Communications.

“Deforestation and degradation are not just focused on dense tropical forests,” says Mitchard, an environmental scientist at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. Wooded savannas, the largest of which lie in southern Africa, are also at risk, he adds.

Much of our understanding of the complex interplay between deforestation, degradation, and regrowth comes from photographs taken by satellites that scientists can then use to compare varying shades of green as a window into what’s happening to the world’s forests.

That works well for the rainforests, which remain green year-round. It doesn’t work so well for wooded savannas, which in the dry season turn brown for part of the year. Once the rains come, leaves return to the trees and grasses blanket the region, further complicating scientists’ analyses.

“Everything is confused by the grasses,” Mitchard says. “We’ve known for a long time that the standard ways of monitoring deforestation do very poorly in these systems.”

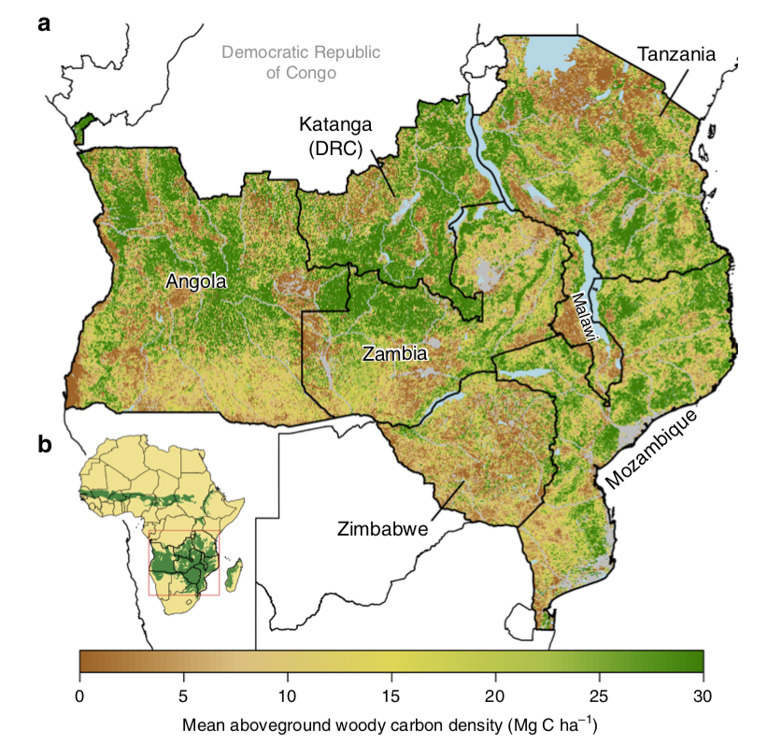

So Mitchard and his colleagues, Casey Ryan and Iain McNicol, took a different tack. They used radar data collected by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency for Angola, Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, as well as the wooded savannas of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The advantage of the radar data is that it “sees the actual biomass in the trees,” Mitchard says. What made it trickier compared to satellite imagery is that the information from radar required “a lot of corrections and processing,” he adds. It also necessitated a host of field plots on the ground to calibrate what they found in the data.

(Graphic: McNicol et al., 2018)

Because it’s been so difficult to resolve deforestation and degradation in woodlands, uncovering the higher rate of deforestation, along with a loss of three to six times more carbon, wasn’t much of a shock, Mitchard says.

“The real big result that we weren’t expecting as much is that we see that degradation is affecting a really large area,” he says, adding that it spans 17 percent of the region. “Over half the biomass loss is due to degradation, which we’ve really had no estimates of before.”

In a ray of hope, they also found that reforestation had occurred in nearly half of southern Africa’s savannas. This offsetting gain in biomass meant that, between 2007 and 2010, the amount of carbon dioxide tied up in the region’s trees held more or less steady at around 6.1 billion tons.

Mitchard and his teammates plan to use more current radar data in further studies to determine whether these trends are continuing across the region.

Predictably, the researchers found that the highest rates of deforestation and degradation occur around densely populated areas. Most prominent among the myriad uses of the forest is likely “unsustainable charcoal harvesting,” mostly for city dwellers’ cooking and heating needs, Mitchard says. Charcoal and raw wood provide almost 80 percent of the region’s energy.

But the influence that charcoal harvesting has on forested areas also presents an opportunity, Mitchard says. Encouraging the use of more efficient cookstoves could help lower the pressure on forests for charcoal. And, more broadly, REDD+ projects, designed to “reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation,” could also provide financing for woodland restoration that could boost carbon stocks and promote economic development.

“There’s actually a lot of carbon that’s stored in savannas and woodlands,” Mitchard says. In addition, “There [are] a lot of people that live there, [and] these are often the world’s poorest.”

“This is an easy win,” he adds.

What’s critical, he says, is to address the causes of degradation before those woodlands disappear completely.

“We’ve shown that this region can recover very quickly, and the forest could come back,” Mitchard says. The hurdles to a forest bouncing back grow much higher in the event of complete deforestation. “Once you lose trees from a landscape, it’s very hard to get them back at all.”

This story originally appeared at the website of global conservation news service Mongabay.com. Get updates on their stories delivered to your inbox, or follow @Mongabay on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter.