In the past few years, 26 coal companies have gone bankrupt and 264 mines have closed. The suffering extends from the smallest companies to the behemoths. The two largest coal producers, Peabody Energy and Arch, lost a combined $1.2 billion last year. Those that haven’t gone bankrupt are trading at small fractions of their values from just five years ago. Between 2009 and 2014, while the Dow Jones Industrial Average rose 69 percent, the Coal Sector Index lost 76 percent of its value. It would be difficult to overstate the industry’s current distress.

Re-structuring and re-focusing would probably help. Many companies are over-invested in the out-of-favor, high-sulfur coal of the Appalachian region. Improved pollution scrubbing technology, which is being installed at many power plants, might also make it feasible to burn a wider array of coal types. Demand from abroad may also keep companies afloat. Coal executives insist these sorts of downturns happen all the time and recovery is just around the corner.

“We know that transition is going to take place,” said then-Peabody CEO Greg Boyce in mid-January. “It has historically and it always will—and it will in the future. Whether it happens this year remains to be seen, based on the level of economic activity.”

More than 60 percent of coal-fired power plants are more than 40 years old, and many are nearing the end of their useful lives.

Although Boyce’s optimism is still common in the industry, it’s worth noting that he stepped down a week after making those comments.

As they say in the world of finance, past performance does not necessarily predict future results. Just because the coal industry came back from, say, the terrible downturns of the 1930s doesn’t mean it will bounce back this time. Industries have collapsed in the past because of disruptive technologies (see: the typewriter), environmental concerns (see: chlorofluorocarbon manufacture), or cheaper alternatives (see: scribes). Coal faces all those problems and more.

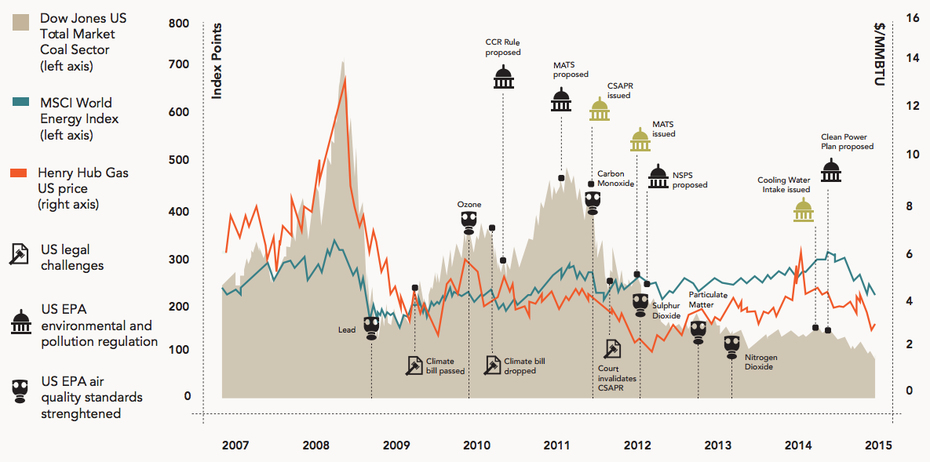

The case against the future of coal starts with its competitor natural gas, which is cheaper. The price of a thousand cubic feet of natural gas at the wellhead dropped from $10.79 in July 2008 to as low as $1.94 in May 2012. There’s no sign of it returning to the highs of the mid-2000s. The Energy Information Administration estimates that the United States has 87 years of natural gas reserves at current consumption rates. Even if we significantly increase our consumption of natural gas, that’s still a pretty big cushion.

The most important and surprising development in the relationship between coal and natural gas has come in the last three years. During that time, natural gas prices rose a bit. A modest rise in natural gas prices should have helped coal companies rebound a little. But instead, the free fall continued.

“Coal and gas are no longer intertwined—there is a structural change,” says Luke Sussams, a senior researcher at the Carbon Tracker Initiative, which published a damning report on the future of coal in March. “There will be variability in the trend, but coal is in a consistent and steady decline.”

The sustained glut of natural gas has encouraged utilities to build gas-fired power plants, a move that locks in the natural gas advantage over coal. In 2013, for example, natural gas represented more than 50 percent of new power generating capacity in the U.S. Coal accounted for just 11 percent, putting it a distant third, behind solar (22 percent) and only slightly ahead of wind (8 percent).

Things are likely to get worse for coal. More than 60 percent of coal-fired power plants are more than 40 years old, and many are nearing the end of their useful lives. With natural gas cheap and likely to stay that way, new gas-fired plants will replace them.

The other pincer closing in on the coal industry is environmental regulation. Coal is one of the dirtiest fuels around. In 2011, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency issued rules to reduce the emission of mercury and other toxics from power plants. Approximately 40 percent of coal-fired plants must add emissions-control technology in order to comply, which will make coal an even more expensive energy source. In contrast, mercury emissions from gas-fired plants are negligible.

“Just as a worker celebrating their 65th birthday can settle into a more sedate lifestyle while they look back on past achievements, we argue that thermal coal has reached its retirement age.”

Carbon rules are an even bigger worry for utilities than mercury emissions limits. Coal is an inherently carbon-intensive energy source, and unless we make a major technological leap, you can’t filter out carbon pollution with a low-cost scrubber. States are already devising plans to comply with the proposed carbon rules, and one of the most obvious and least expensive strategies is to replace coal with natural gas, which emits about half as much carbon.

Utility executives may not be known for their spirit of conservation, but they do care about money. In the current environment, coal-fired power plants are, indisputably, extremely risky investments.

The Energy Information Administration, for the record, doesn’t buy this view. The agency projects modest growth in coal combustion through 2040, in part because the EIA is bearish on renewables. Last year, the EIA estimated that renewables would make up just 16 percent of U.S. electricity generation in 25 years, only slightly up from the current 13 percent contribution. Many analysts reject those projections.

“Things are moving quickly in coal and renewables right now,” Sussams says. “I’m not sure big commentators like the EIA are amending the fundamental assumptions that underpin their models.”

If this decade represents the beginning of the end for coal, it’s likely to be a very slow process. Consider the case of industry giant Arch Coal. The company has $1.8 billion in debt due in 2018, another $1.7 billion the next year, and $1.5 billion in 2021. It’s unlikely that the company will be able to come up with that cash, because investors won’t loan them more money on favorable terms. Bankruptcy lawyers will restructure the debt, and stockholders will lose their investment. But the company will still be around.

“There is too much intrinsic value in big companies to disappear entirely,” says Theo Spencer, senior advocate at NRDC’s climate center. “They have long-term contracts to sell coal, and they have mining equipment. Bankruptcy doesn’t mean death. Demand for coal isn’t going away in 10 years.”

Goldman Sachs takes a similar view. The renowned house of money declared in January that it’s time to slowly ease coal out of the energy mix, with a friendly pat on the head for all the good it did for the U.S. economy.

“Just as a worker celebrating their 65th birthday can settle into a more sedate lifestyle while they look back on past achievements,” the report noted, “we argue that thermal coal has reached its retirement age.”

This post originally appeared on Earthwire as “The Black Death” and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.