Every year, coal-fired power plants in the United States produce over 100 million tons of ash laced with toxic heavy metals, much of which is mixed with water and stored in unlined pits nearby. These ponds, like the plants that fill them, are often located next to waterbodies like rivers or lakes. Environmentalists and public-health officials have long raised concerns that harmful chemicals could leach into groundwater or overflow into rivers and streams during heavy rains and contaminate drinking water sources. A new report out Monday finds that there’s merit to these concerns: At least 36 coal ash ponds are located in flood zones.

The report’s findings were released on the final day of the comment period for a new Environmental Protection Agency rule rolling back Obama-era regulations of coal ash disposal. In 2015, following several high-profile coal ash leaks, including a 2008 spill in which a dike broke at the Kingston Fossil Plant in Tennessee and 1.1 billion gallons of ash poured into the Emory River, the Obama administration proposed new standards for coal ash ponds that included more monitoring and inspections and stricter lining requirements.

The rule never took effect. Utility industry officials, citing the “excessive costs of compliance,” blocked the rule from implementation with litigation until the Trump administration, which has been much more sympathetic to industry interests, took office. In March, the EPA announced several changes to its coal ash regulations, giving more power to states to set their own ash-disposal standards and saving the industry up to $100 million a year in compliance costs.

The agency is expected to move forward quickly with a final rule now that the public comment period has closed. But the authors of the new report highlighting the dangers of coal ash ponds say that weakening the standards now is just “inviting disaster” along rivers that provide drinking water to millions of Americans.

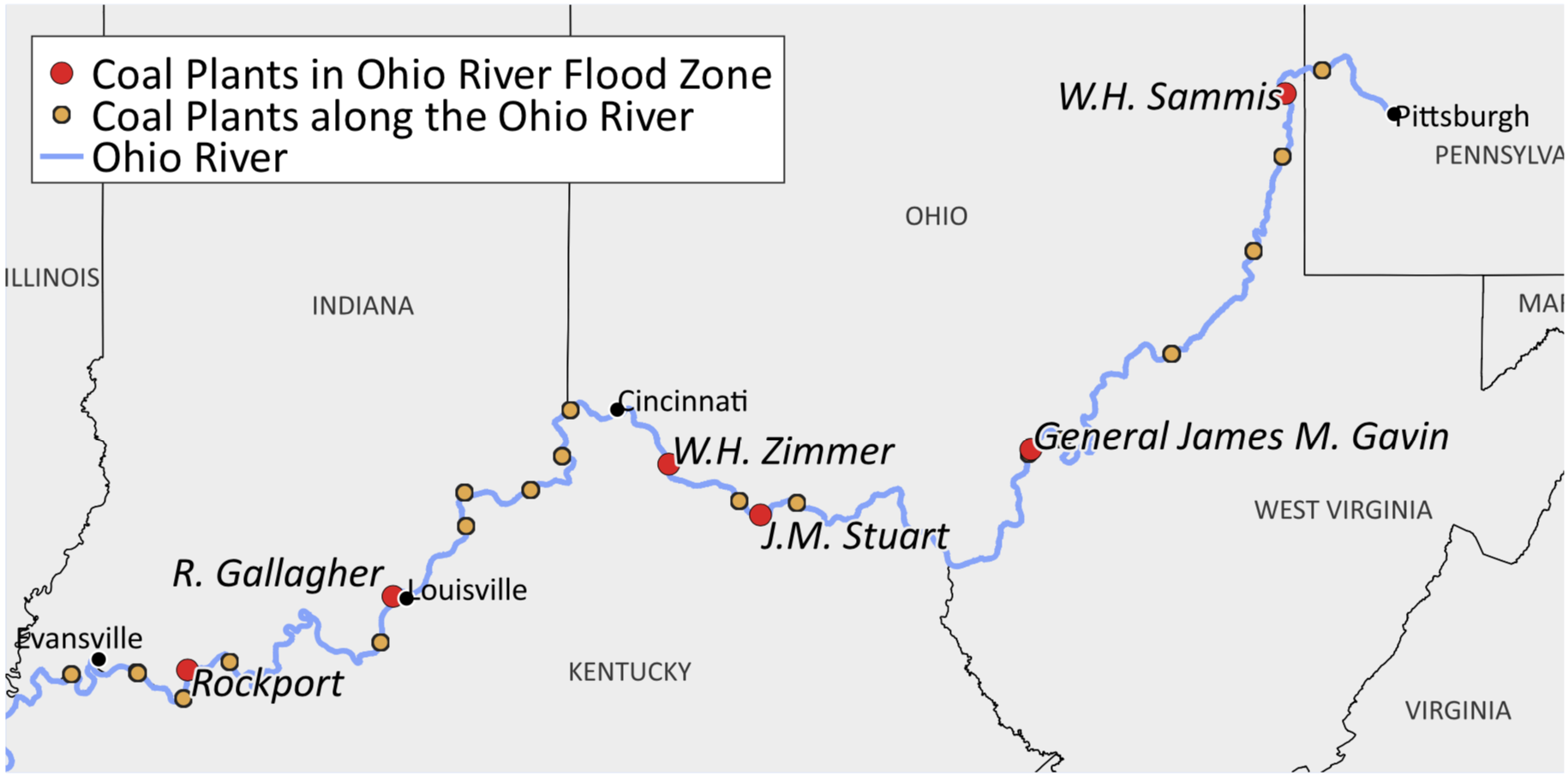

The authors compared coal-fired power plant locations with Federal Emergency Management Agency flood maps, and found that 14 plants and 36 ponds were within FEMA’s 100-year flood zones—regions with a 1 percent chance of flooding in any given year. The Ohio River, which supplies drinking water to at least three million Americans as it flows from Pennsylvania to Illinois, where it empties into the Mississippi, is a hot spot. Six of the 14 plants identified were located on its banks.

(Map: Environment America Research & Policy Center/U.S. PIRG Education Fund/Frontier Group)

Five of those coal-fired plants associated with 11 ponds along the Ohio River were included in a 2014 EPA assessment of coal ash pond conditions and hazards, based on potential environmental and economic damages of spills. Four of the 11 ponds along the river posed a “high” or “significant” hazard.

The report calls for a moratorium on new coal ash ponds and for current ponds to be excavated and transferred to lined and carefully monitored landfill sites far away from bodies of water. “We should be phasing out these toxic pits,” John Rumpler, the director of Environment America Research & Policy Center’s clean water campaign and study co-author said in a statement Monday. “The last thing we should be doing is weakening the few standards we already have in place to limit their pollution of our waters.”