California lawmakers are working on a historic plan — the first of its kind in the United States — to require a 20 percent reduction in per-capita urban water use by the year 2020. It signals the end of cheap water for water wasters, a change that’s bound to come as a shock to some residents in the Golden State.

This spring, more than 2,000 people living in and around the populous High Desert community of Palmdale — 60 miles north of Los Angeles — wrote letters of protest after their water district, teetering on the brink of bankruptcy, dramatically raised hikes in rates and service charges. Residents are just now getting their bills, and the district’s phone is ringing off the hook with customers asking for waivers.

The city of Palmdale announced drastic cuts to irrigating local parks in response to what it said were “extreme hikes in water rates.” And it filed suit against the Palmdale Water District, arguing that the increases were illegal and the formula for computing customers’ bills was incomprehensible.

“They perceive that they’re being the champions of the people,” district General Manager Randy Hill said of city officials, “but we don’t have sufficient water supplies. We’re at the point that our demand is dangerously close to our supply. We should have been raising rates all along, and we didn’t.”

It’s a conservation rule of thumb that if a resource is underpriced, it will be overused. And California needs every drop, experts say, to cope with recurring droughts, serve the growing population and restore the fragile Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, the source of much of the state’s fresh water, including Palmdale’s.

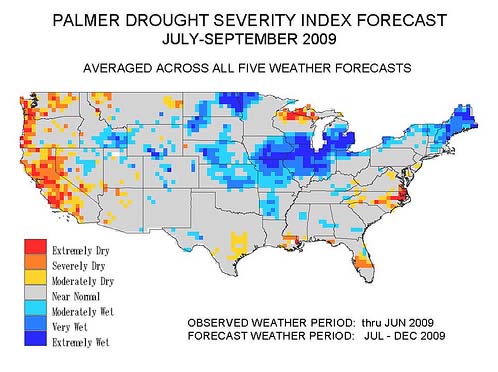

“Sooner or later, California will be hit with the same kind of prolonged, severe drought that Australia is facing now,” said Rick Soehren, assistant deputy director for water use efficiency at the state Department of Water Resources and co-chair of the “20×2020” planning team. “Either we’re going to be ready, or the economy takes a terrible hit and people lose a huge investment in landscaping.”

The draft plan was made public this year by a state and federal team under a directive from Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger. It opens with the statement that California’s “overall demand for water has exceeded our reliable developed supply.” In just over a decade, it proposes to reduce California’s urban water use — residential, commercial and industrial — from an average 192 gallons per person per day to 154 gallons. That would be an annual savings of about 1.7 million acre-feet, equivalent to more than a two-year supply for Los Angeles. (The national urban per-capita use is 101 gallons per day, reflecting the higher average rainfall in many states.)

Palmdale residents use 200 gallons per capita daily. John Mlynar, a city spokesman, said the city has been trying hard to cut water use on its own property, reducing it 27 percent in recent years, even installing artificial grass in front of city hall.

“We have gone to great lengths to conserve water,” Mlynar said. “The district needs to look at cutting some expenses before passing on costs.”

A Los Angeles Superior Court judge declined to temporarily halt Palmdale’s water rate increases this month, but the city’s lawsuit is going forward. In the meantime, the water district is spending tens of thousands of dollars on legal costs — money that Hill, the general manager, said he could be using to pay residents to put in low-flow toilets and take out grass.

Statewide, experts say, water districts like Palmdale will have to change the way they do business to meet the proposed 20 percent reduction in urban water use. It’s an average: State Assembly bill AB 49 would allow water districts to use different formulas for meeting the goal, taking into account differences in climate and levels of conservation already achieved.

“In areas where there has been more aggressive conservation, the reduction could be 17 percent, whereas in other areas it could be as high as 30 percent,” said Chris Brown, executive director of the California Urban Water Conservation Council, a nonprofit group that helped develop the plan.

After some fine-tuning by a joint committee of the state Assembly and Senate, AB 49 is expected to go to vote this fall. It is sponsored by the National Resources Defense Council, a national environmental group, and the giant Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. It also has the support of the Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce and numerous other business and environmental groups and water agencies.

Proponents of the 20×2020 plan say it means cutting back on water waste, not lifestyle — fixing leaks; installing low-flow toilets, showerheads and washing machines; adjusting irrigation; and putting in drought-tolerant plants.

“Most homeowners in California still have grass,” Soehren said. “We’re starting to chip away at that, either by persuading people to water their lawn more efficiently, or convincing them they don’t need a lawn in the front where no one plays on it. There definitely is a water crisis, and it’s hard to justify using all you want just because you can get a hold of it.”

Bob Wilkinson, a University of California, Santa Barbara professor who serves on the technical advisory committee for the California Water Plan, believes residents could easily achieve as much as a 30 percent reduction in just a few years.

“The No. 1 source for new water is urban water use efficiency,” Wilkinson said. “It’s not a sideshow, and it’s important that people not think of this as a sacrifice. It wouldn’t take draconian measures. We just need to get price signals in place to help people understand the real price and cost of water.”

That’s what’s happening in Montecito, a wealthy community on the coast northwest of Los Angeles, where residents were paying three times as much for water as in Palmdale but didn’t care about the cost because they could afford it. Newcomers who had no memory of the drought of 1986-91 tended to build big homes with big lawns.

While water demand flattened out in the rest of Southern California, including Los Angeles, Montecito’s grew until it reached a local record in 2007 of more than 350 gallons per capita per day. That’s one of the highest per capitas in the state, equivalent to that of people living in California’s Sonoran Desert, near the border with Mexico.

“Everybody put in their lush landscaping,” recalled Tom Mosby, the Montecito Water District general manager. “Money wasn’t an issue. I would see trucks going up the street with sod and I was just having a heart attack.”

Suddenly, Montecito was confronting the possibility of a chronic, long-term water shortage. In the short term, the district spent nearly $900,000 buying surplus water from the state aqueduct to make ends meet. For the long term, it set a limit on water for new development and restored a tiered rate structure similar to the one it had implemented during the last drought. Now customers are charged progressively more for each successive tier or “block” of water they use — a pricing method recommended by the state.

Montecito is on track to achieving a 10 percent reduction in water use by this October, a year after the new rates went into effect, Mosby said.

“At first, the bills were a major shock for everyone,” he said. “The community’s got the message, and we are very pleased.”

Yet even with a 10 percent reduction, Montecitans would still be using nearly three times as much water per capita as the residents of Goleta, a suburban community just 12 miles up the coast. At 111 gallons per capita per day, the customers of the Goleta Water District are among the most conservationist in the state.

During the last drought, Goleta gave out $50 rebates for 15,000 low-volume toilets, importing them from Sweden. It was the first toilet rebate program in the country: The slogan was, “You’re Sitting on the Solution.” In addition, the district gave away 40,000 low-flow showerheads. It implemented water rates that went up steeply in the highest tiers. Many homeowners took out their lawns. Water demand dropped by 40 percent, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency singled out the district as a model in conservation.

After the last drought ended in 1991, Goleta’s water rates stayed high. Although not as high as Montecito’s new rates, they are easily twice the average rate in California today. Goleta faces no water shortages today, even in the current drought. Residents here are on the lookout for waste: Every week, someone calls the district to report a neighbor who’s letting water run down the street.

“Historically, this district has been preaching conservation and, in my humble opinion, doing a damn good job,” said Jack Cunningham, a member of the Goleta Water District board of directors. “It’s taking hold and being retained by a lot of users because they can remember the last drought. We don’t feel an urgent need for ’20×2020.’ I do my own rationing as a house owner in Goleta.”

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Become our fan.

Follow us on Twitter.