On Feb. 7, 1812, a magnitude 7.7 earthquake pummeled the Mississippi River town of New Madrid. The quake, which was then the largest in U.S. history, was the fourth temblor to hit the region in a three-month span, and newspapers reported that people as far away as New York and Charleston, S.C. felt the vibrations. In one account, the shaking centered in the Louisiana Territory, about 150 miles south of St. Louis, caused bells to toll out of turn in Boston.

Even though hundreds of smaller quakes occur annually in the New Madrid Seismic Zone, scientists are at a loss to explain when and how the area’s faults become more active. Nothing as potent as the 1811-12 quakes has happened there since then. Plus, New Madrid is roughly at the center of the North American continent, thousands of miles away from the plate boundaries normally associated with seismic and volcanic activity.

“There’s geologic evidence that something about this area is different,” said Chuck Langston, director of the Center for Earthquake Research and Information (CERI) at the University of Memphis. “Gravitational pull is stronger there; it could be because of greater mass [below the surface].”

To gain a greater understanding of the subsurface geologic structure, researchers started a moving, continent-wide imaging effort called EarthScope. As it creeps across the continent, Earthscope measures subsurface conditions in multiple ways — one geologist compares it to giving North America a series of CT scans and MRIs — allowing scientists to compare different models and create a clearer, more complete picture of what it looks like down there.

“If you actually looked at the geologic features under the surface, it would be as striking as looking at the Himalayas,” Langston explained.

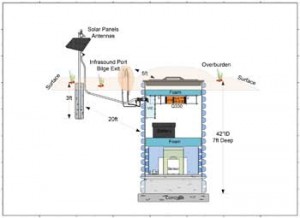

Before the project began in 2004, subsurface data collection was limited to sporadic seismograph stations and isolated study areas, such as the New Madrid Seismic Zone and the Yellowstone Caldera, another mid-plate anomaly. The seismic measurement stations associated with EarthScope — dubbed USArray — consists of about 400 mobile seismometers and a smaller number of instruments designed to measure the electromagnetic properties of subsurface rock. Spaced 70 kilometers (43 miles) apart, the transportable array is the densest system of seismological equipment ever devised; the tight grid allows seismologists to sample the detailed 3D structure of the earth from the crust-mantle boundary to the lower mantle, a depth of nearly 3000 kilometers.* The grid is set to fill the voids left by the more scattered seismograph stations that were already silently gathering data. Technicians travel around the lower 48 throughout the year — avoiding extreme temperatures by concentrating on northern stations in summer and southern ones during winter — pulling up and re-positioning about 200 stations annually. (Each station records data for about two years before being removed.) Moving from west to east, the project has only recently reached New Madrid, but progress has picked up as the teams leave behind the challenging terrain of the Rocky Mountains.

“I kind of think of it as a scan of the continent,” said Bob Woodward, USArray’s director, and the director of instrumentation services at Washington, D.C.-based Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology, or IRIS. “The thing that comes out of USArray is a much clearer picture of the structure below the surface.”

The array provides detailed information through a process called seismic tomography. Each super-sensitive seismograph can pick up earthquakes of magnitude 5.0 and greater on the opposite side of the planet, and smaller ones nearer the seismometer. Receiving signals from below in all directions, scientists are able to create high-resolution images to help them better understand the makeup of North America’s baffling geology.

“The continent that the U.S. sits on has been pulled apart and smashed together quite frequently,” said Woodward. “It’s complex, and this helps [scientists] put it all together.”

A phalanx of institutions cooperate to run EarthScope, the key players being the IRIS, the University Navstar Consortium (which operates the Plate Boundary Observatory), Stanford University, the U.S. Geological Survey, and NASA. The National Science Foundation funded the project with a 10-year grant, of which the seismic monitoring portion alone costs about $9 million annually.

EarthScope also has a seismic equipment pool — “kind of like a lending library for seismic instruments,” as Woodward calls it. With hundreds of instruments available for more specific National Science Foundation approved and funded projects, EarthScope lends out equipment for locally focused “detail shots” within the general continental scan. Most of the gear is currently checked out, said Woodward, operating in seismic studies in parts of Wyoming, Missouri, Georgia, Idaho, Nevada, Minnesota, and Illinois.

One of EarthScope’s other detail-oriented facets is the magnetotelluric observatory — about 50 portable instruments designed to collect subsurface electromagnetic data from depths of up to 100 km. Much of the study’s attention has been focused on the Yellowstone Caldera, a subterranean supervolcano sitting atop a plume of magma extending into the Earth’s crust from its molten mantle. Geologists believe there have been a number of earthquakes and super-eruptions there over the past 18 million years, leaving behind a series of craters and geothermal vents — including the famous geyser, Old Faithful — at Yellowstone National Park.

The massive chamber of trapped magma and pressurized gases have even recently caused visible changes in Yellowstone’s elevation — for a few years after 2004, the ground rose an average of 7 centimeters, a little under 3 inches, per year before subsiding again after 2011 — as well as thousands of minor earthquakes (known as swarms when they occur in clusters over a short period of time) every year. The caldera could blow again at any time, but no one knows when or how big the blast would be.

Yellowstone is no stranger to quakes. A magnitude 7.5 earthquake struck in August 1959 — at the height of tourist season — causing a landslide that killed 28 people. The slide also created Quake Lake when it blocked the Madison River.

*This originally gave a figure of 70 kilometers for the readings, a depth about 43 times less than actually being detailed.Back

Sign up for the free Miller-McCune.com e-newsletter.

“Like” Miller-McCune on Facebook.

Follow Miller-McCune on Twitter.

Add Miller-McCune.com news to your site.