After an intensely controversial 21-month tenure, Ryan Zinke is out at the Department of the Interior (DOI), pressured to resign by a White House wary of his many scandals.

Zinke leaves as his legacy a littering of ethical snafus and industry handouts, and so his departure is being met with enthusiastic applause from green groups, Native American tribes, outdoor businesses, and scientists.

But the conservation community has only partial cause for celebration, because Zinke’s influence will live on at the DOI, a sprawling federal agency that manages some 500 million acres of public land across the country, or a fifth of the United States’ landmass.

As he prepares to step down in January, Zinke leaves behind him a slew of conservative operatives and industry sympathizers embedded throughout his department. These political appointees, whom the secretary installed in key positions at the agency, are the architects of some of the DOI’s most controversial decisions. By all accounts they will continue to pursue the Trump administration’s anti-conservation agenda for the remainder of their time in office.

Here’s a list of some of the Department of the Interior power players that are still in control of America’s public lands, despite Zinke’s early departure.

David Bernhardt

The most high-profile political appointee still standing at the DOI is David Bernhardt, who served as Zinke’s No. 2. Bernhardt is expected to step in as acting secretary after Zinke officially resigns in January. A former oil and gas and water industry lobbyist, he is known as a whip-smart bureaucrat with a firm understanding of the mechanisms of government. He appears to be able to manage a wide variety of top-line policy tasks, from rolling back endangered species safeguards to easing oil and gas regulations, without leaving much of a paper trail.

“We’ve said all along that David Bernhardt is a walking conflict of interest, and that’s been borne out since his confirmation,” says Aaron Weiss, the media director at the Center for Western Priorities, a pro-conservation watchdog group. “While Ryan Zinke consistently embarrassed himself in public, Bernhardt quietly went about his job implementing policies that help his former clients.”

Bernhardt is already receiving a great deal of media attention as Zinke’s heir apparent. But to get want a sense of the man’s conflicts of interest, consider a recent analysis from CWP that shows how dozens of Bernhardt’s former lobbying clients have benefited from DOI decisions since Zinke and his team took power. Former Bernhardt clients like the Independent Petroleum Association of America, for instance, have undoubtedly watched with pleasure as the DOI has rolled back a wide variety of oil and gas regulations, including the Obama-era methane rule. And the major federal water contractor and former Bernhardt client, Westlands Water District, stands to benefit in a big way as the Trump administration moves to weaken imperiled wildlife protections and divert more California water to Western agricultural producers.

With Bernhardt as the de facto leader of the DOI, these interests and others like them ought to be rejoicing.

James Cason

James Cason is a little-known conservative operative who has worked for multiple Republican administrations at the Department of the Interior. He is currently serving as the DOI’s associate deputy secretary, a position of immense power. Cason has used that power to help engineer some of the department’s most controversial decisions. He was the political appointee, for instance, who signed off on the reassignment of a slew of senior civil servants at the department early in Zinke’s tenure. These involuntary reassignments led at least one top DOI staffer—Joel Clement—to resign in protest and blow the whistle after he was transferred from a top policy job at the agency to an obscure accounting position. Clement believes his reassignment was politically motivated retaliation for his past work studying and speaking out about the dangers of climate change.

“Jim Cason went to the David Bernhardt school of agency subterfuge, which teaches that you can do whatever you want as long as you stay out of the public eye, keep industry happy, and never, ever put anything in writing,” Clement, who is now a senior fellow at the Union of Concerned Scientists, wrote in a statement to Pacific Standard. “He knows that the best way to serve his industry masters is to hamstring the regulatory, science, and conservation mission at Interior, and in doing so disregard the interests of the millions of American taxpayers who value public lands that are not strewn with oil and gas derricks.”

Doug Domenech

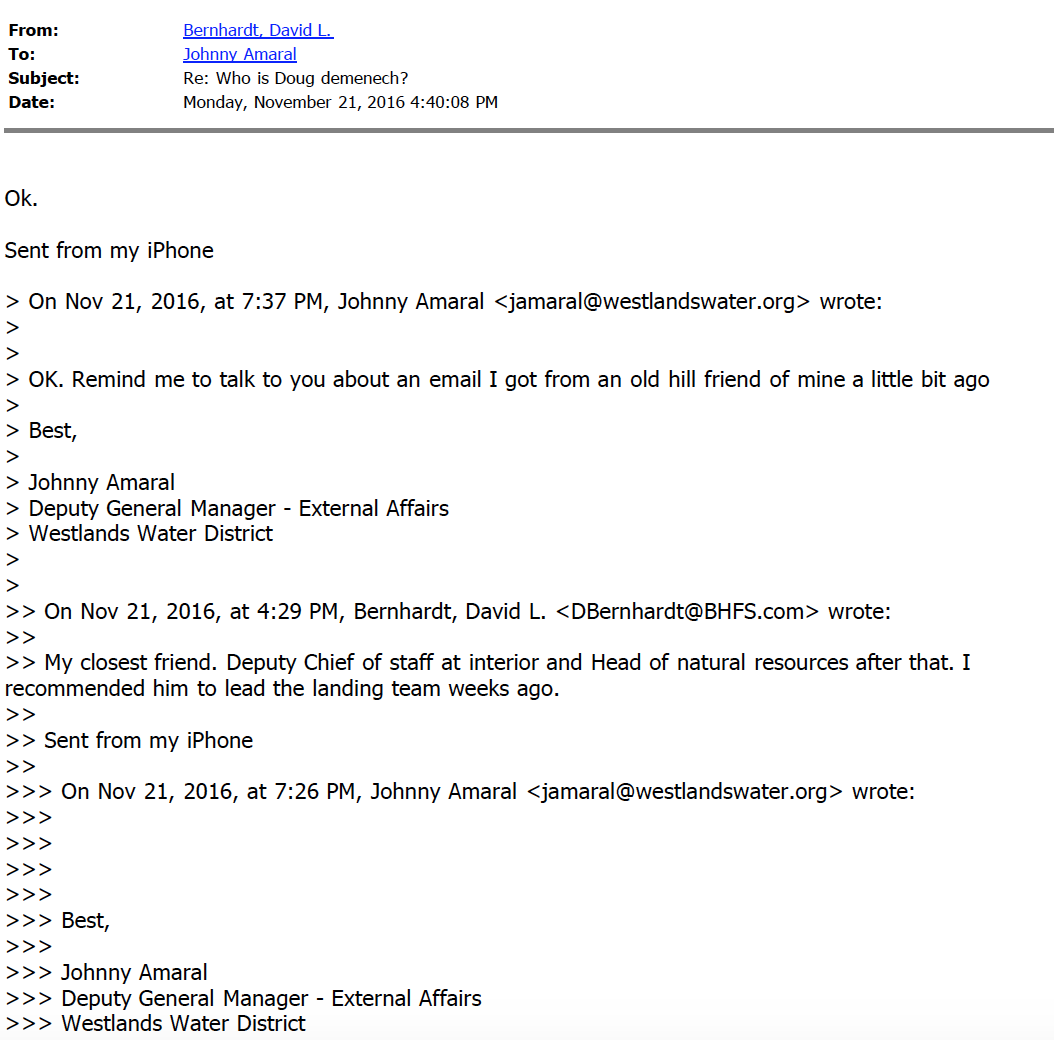

Douglas Domenech, the assistant secretary for insular affairs at the Department of the Interior, is a long-time foot soldier in the conservative movement. A former employee at the Koch-linked Texas Public Policy Foundation, he led the Trump administration’s landing team at the department in early 2017. He is also Bernhardt’s close friend, according to email correspondence obtained by Pacific Standard:

Domenech has largely avoided public scrutiny during his time at the DOI, although he appears to be a key point of contact between political officials at the agency and members of conservative ideological organizations around the country. For instance, in June of 2017 he organized an important meet-and-greet between top DOI officials and members of the Koch-linked State Policy Network, an alliance of right-wing think tanks around the country that ardently oppose most environmental regulation. Domenech also met twice in 2017 with his former employer, the Texas Public Policy Foundation, to discuss two lawsuits it had filed against the DOI, according to his official calendars. The meetings with TPPF appeared to be a direct violation of federal ethics rules, which bar federal officials from holding certain meetings with former employers.

Daniel Jorjani

Daniel Jorjani is another veteran conservative politico that Zinke installed at the DOI. A former top official at the Koch-backed Freedom Partners and currently the principal deputy solicitor at the DOI, he is charged with shaping the department’s legal strategy. He personally signed off, for instance, on a legal opinion rolling back environmental protections under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, a century-old law that is crucial for the conservation of a wide range of imperiled bird species but which occasionally inconveniences energy companies. After meeting with mining lobbyists, he also signed a legal opinion that helped advance a proposed metal mine on the outskirts of the Boundary Water Canoe Area Wilderness in Minnesota. In November, meanwhile, Zinke placed Jorjani in charge of the DOI’s Freedom of Information Act program, a move that conservationists and government transparency groups alike fear will politicize the agency’s handling of public records request.

Katharine MacGregor

For much of her nearly two-year stint at the DOI, Katharine MacGregor has served as the deputy assistant secretary for lands and mineral management, a position from which she oversee the Bureau of Land Management and much of America’s publicly owned oil, gas, and coal reserves. MacGregor, a former Congressional staffer, has been a key figure in promoting the interests of fossil fuel companies. During her time at Interior, she has taken scores of meetings and phone calls with oil, gas, coal, and other energy interests. She was personally involved in canceling a government-funded study into the health impacts of mountaintop removal coal mining in Appalachia. And she had a part too in rolling back an Obama-era regulation that sought to limit methane pollution from oil and gas drilling on federal lands. Indeed, MacGregor has been so useful to oil and gas interests that the Western Energy Alliance, an aggressive industry trade group based in Denver, personally commended her in a letter it sent to Zinke in December of 2017.

“We wish to specifically recognize the efforts of Kate MacGregor regarding executing on the energy dominance agenda overall,” wrote WEA’s president, Kathleen Sgamma.

MacGregor has since been promoted to the role of deputy chief of staff at the DOI.

Kathleen Benedetto

Kathleen Benedetto is another long-time Congressional staffer who joined the DOI in the early days of the Trump administration. A zealous advocate for the mining industry and a co-founder of the Women’s Mining Coalition, Benedetto is now a senior adviser at the DOI, where she helps oversee the Bureau of Land Management. Much like MacGregor, Benedetto has opened her doors to mining and fossil fuel interests, holding scores of meetings and phone calls with extractive industry executives and lobbyists during her time at the department. Benedetto also took the lead on the Trump administration’s rollback of the Obama-era sage grouse conservation plans, which eliminated protections for the imperiled Western bird and made millions of acres of Western land more readily available to oil and gas drillers, mining companies and more.

Tim Williams

Tim Williams, a former employee at the Koch-backed advocacy group Americans for Prosperity, now serves as the deputy director of the DOI’s office of intergovernmental and external affairs. Throughout his time in office, Williams has exhibited exceedingly close ties to industry and conservative groups. Early into his tenure, for instance, he participated in a meeting with AFP, his former employer, to discuss the group’s “shared priorities” with the DOI, according to his official calendar. The meeting was an apparent violation of the White House ethics pledge.

Williams also spoke at an energy-industry-sponsored policy summit in Washington, D.C., in December of 2017, where he told a group of oil and gas industry executives and conservative activists about the department’s plans to rollback environmental protections put in place by the previous administration.

“You guys should know that if you have any questions or any problems you feel free to contact me,” he told his audience, according to documentation of the event obtained by Pacific Standard. “That is my job, to work with industry.”

The list above, of course, is not comprehensive. There are many other DOI political appointees deserving of public scrutiny, including people like Acting Assistant Secretary Susan Combs, an ardent opponent of the Endangered Species Act, as well as former officials like Energy Counselor Vincent DeVito. They may well get it. After all, as a result of Zinke’s tenure at the DOI, more people are paying close attention to the agency. What’s more, Democrats are about to take power in the House of Representatives. Come January, they will have both subpoena power and what’s likely to be an insatiable appetite for investigating the activities of top political appointees in the Trump administration, including those at the DOI.

Ultimately, here’s the upshot: The DOI’s impact on American life is difficult to overstate, and whether Zinke is in or out of office, a cohort of right-wing industry advocates still wield huge influence over the agency.