With the worst drought in 70 years decimating northern China’s winter wheat crop and the soybean harvest down 40 percent in Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay this year, the world food crisis continues to expand — even as increased demand for plant-based biofuels further strains agricultural lands. What’s more, by midcentury an estimated 80 percent of the world’s population will live in urban areas. Feeding these new city dwellers will require creative ideas to reduce food miles and the associated energy use.

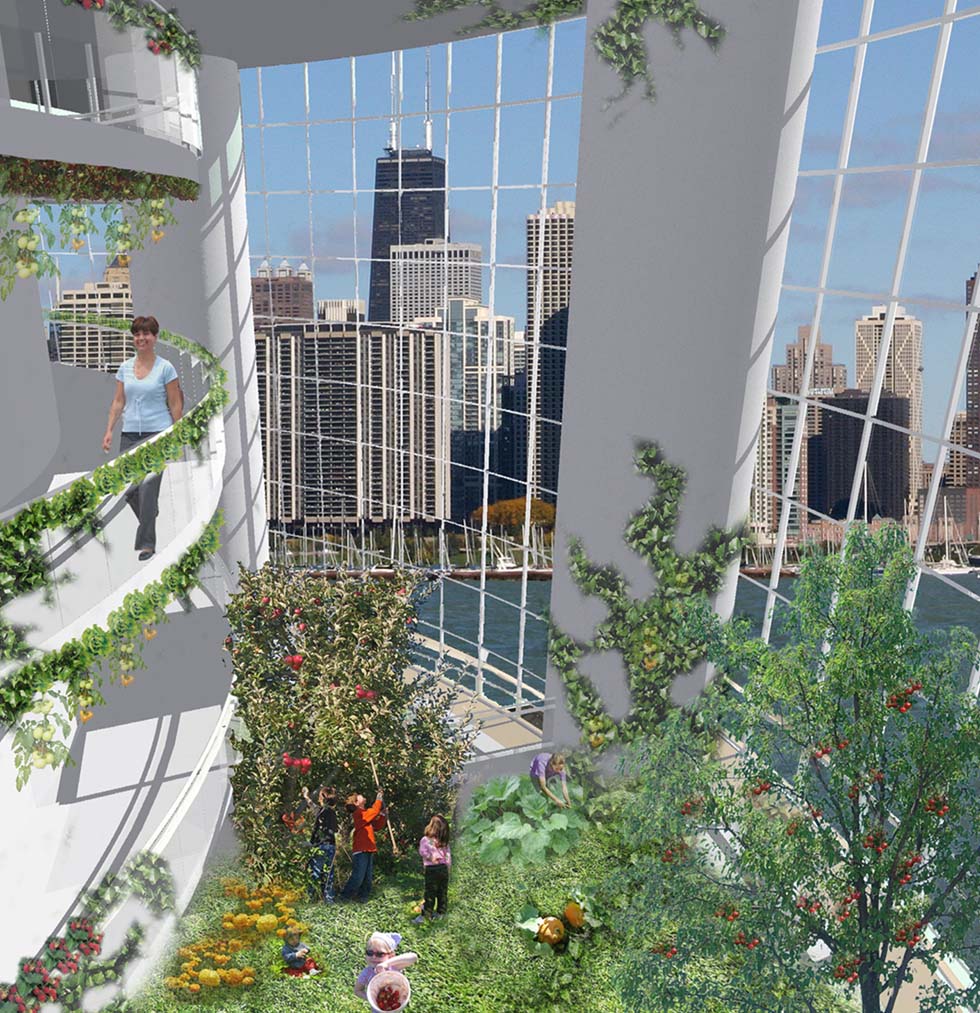

One solution may lie in Dickson Despommier‘s vertical farm — a 30-story crop powerhouse the size of a Manhattan block that, in theory, could produce enough food for 50,000 people.

The concept took root in 1999 while Despommier, a parasitologist, was teaching medical ecology at Columbia University’s School of Public Health. Halfway through the semester, his students, tired of exploring the health risks associated with environmental damage, asked him if they could do something more “uplifting.”

“OK, it’s your money, and it’s your time,” Despommier told them. “Pick a subject and I’ll be glad to support you.”

After choosing rooftop gardening, Despommier challenged the class to see how many Manhattanites they could feed on a 2,000-calorie daily diet. With only 13 acres of usable rooftops, the students could only cover 2 percent of those 50,000 people. “Not good enough,” Despommier responded.

Sensing their frustration, Despommier flippantly suggested growing stuff indoors — vertically. By accident, the 69-year-old had found a new calling, and by 2001 the project had evolved into a vertical farm. Using grow lights and conveyor belts powered by renewable energy sources, Despommier and his students came up with an outline in which approximately 100 kinds of fruits and vegetables would grow on upper floors with lower floors housing chickens and fish subsisting on the plant waste.

This may all sound like pie in the sky, but Despommier says his skyscraper farm has aroused the interest of scientists and investors around the world. And though the project is still in the blueprint phase, if it pans out, not only will large numbers of individuals be able to source their food locally, but ecosystems destroyed by years of exposure to toxic pesticides will also be restored.

Miller-McCune.com: You believe that we need to systematically abandon farmland. Why?

Dickson Despommier: Right now the agricultural footprint of the Earth’s population is the size of South America. That’s an enormous amount of land that we set aside for farming. We’re at 7 billion people. In another 40 years, we’ll be at 10 billion. To continue farming as we do now, we’ll have to set aside new land the size of Brazil. That would lead to the collapse of numerous ecosystems on this planet, and we would go with it.

People say, “Food in buildings? How unnatural? The natural thing is to use the land.” Well, I hate to break this to you, but that’s equally unnatural. That farm used to be an intact ecosystem until we transformed it. Vertical farms will restore the natural capital of the land and provide our food at the same time.

M-M: So even if there weren’t a starvation issue, you’d still advocate restoring farmland?

DD: The biggest problem the Earth’s human population and other animals and plant populations face right now is the rapidity of climate change.

Climate change will happen regardless of what we’re doing, but the speed at which it occurs is our fault. That’s the part we control by the emissions, primarily from our C02-producing combustion engines and from our animal husbandry via methane production. The part we can address the most is carbon sequestration. How do we take that carbon out of the atmosphere? The Food and Agricultural Organization of the U.N. says the best way to do it this to allow trees to regrow in places they used to be.

M-M: You’re a parisitologist. What’s the connection to vertical farms?

D-D: Half of the world still uses human feces to fertilize crops. That’s the best way I know of to acquire parasitic infections, particularly worm infections, which take a great toll on human health. If the world could learn to grow its food differently, we could cut off the lifecycles of these incipient parasites. Also, modern farming methods that rely on chemical pesticides and herbicides have created additional health risks that are only now being investigated by epidemiologists and toxicologists.

M-M: But what about organic farming? Won’t that help offset the bigger problem?

DD: You simply can’t farm organically on a scale large enough to solve the rapidity of climate change. There just isn’t enough good soil out there. In fact, the FAO says the biggest detractor for agriculture nowadays is soil erosion that occurs either from wind, because of droughts — and there are tons of drought situations out there — or from flooding. Both situations result in topsoil loss, the biggest reason for the world’s current agricultural predicament.

M-M: OK, but what about the pleasure and physical benefits that traditional farming brings?

DD: I love that aspect of farming, and I wish that life could continue unchanged, but to be very honest, the world is transforming before our very eyes. Ask the average farmer. They’ll tell you they’ve had their worst droughts and floods in their history — within recent memory.

We have to face up to the fact that climate disruptions are becoming more rather than less frequent. We’ve only had two F-5 tornadoes in the world and they both struck in the American Midwest just during the last five years. Wipe a farmer out for three years in a row and they’re out of business.

Take the farmers in India, where I just visited in February. All I kept hearing about was the failure of the monsoons. They used to last four months, with relatively gentle rain recharging the aquifers, which provided water for a whole year. Now the monsoons come for two and a half months. It rains like crazy and though you get the same amount of water, everything gets washed away. The cotton failed this year; wheat last year.

M-M: So how do vertical farms offset this?

DD: I’ll give you two choices. First one is you get to control everything from start to finish. The second is you get to control nothing. Which one do you pick? Choosing the first one is natural, but farmers don’t have that choice. They can’t control the weather. Our farming technology includes hydroponics, which uses 70 percent less water than normal agriculture. We also use aeroponics, which uses 70 percent less water than hydroponics. Indoors, we can control everything including temperature and humidity as well as nutrition.

M-M: How does it work?

DD: Each floor will have its own watering and nutrient monitoring systems. There’ll be sensors for every single plant that tracks how much and what kinds of nutrients the plant has absorbed. You’ll even have systems to monitor plant diseases by employing DNA chip technologies that detect the presence of plant pathogens by simply sampling the air and using snippets from various viral and bacterial infections. It’s very easy to do.

Moreover, a gas chromatograph will tell us when to pick the plant by analyzing which flavenoids the produce contains. These flavenoids are what gives the food the flavors you’re so fond of, particularly for more aromatic produce like tomatoes and peppers. These are all right-off-the-shelf technologies. The ability to construct a vertical farm exists now. We don’t have to make anything new.

M-M: So who’s going to pay for this? Where is the money going to come from?

DD: There are governments out there willing to get involved because they lack a readily available food supply since they don’t have any soil. Jordan has expressed a big interest. In those places, I’d enlist federal support.

We’ll also use private investors of course, but to start doing this off the bat would be impossible. You experiment, work out all the kinks, find out where the weak points are and you try to strengthen them. You do good science, which means starting with prototypes and putting them into the hands of experts who then tell you how to save money, what building materials to use and the kinds of crops that would be most effective.

M-M: What are some of the biggest challenges with this endeavor?

DD: Coordinating all these systems into an engineering schema that allows each floor to act independently yet integrated into the flow of water, nutrient delivery, planting, growing and harvesting. All of that needs to be worked out. That’s why we’re advocating for a prototype vertical farm first to be located perhaps in a very gifted agricultural school’s campus, next to a very large city, so you could use the city as your experimental playground for integrating versions of vertical farms into restaurants, schools and hospitals, etc.

M-M: You say that if vertical farming succeeds it’ll establish the validity of sustainability irrespective of location.

DD: For the first time in the history of human existence, farming won’t have to rely on soil types. You’ll be able to build a farm in the middle of a desert or in Iceland. You’ll put it wherever you want and people will live there as a result, because you can generate food and energy in those places. Now the water has to be obtained from the ground but if you dig deep enough you’ll find it. You don’t need a lot for hydroponic farming. That’s why it’s worth it no matter what you do have to do to drill for it.

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Become our fan.

Follow us on Twitter.