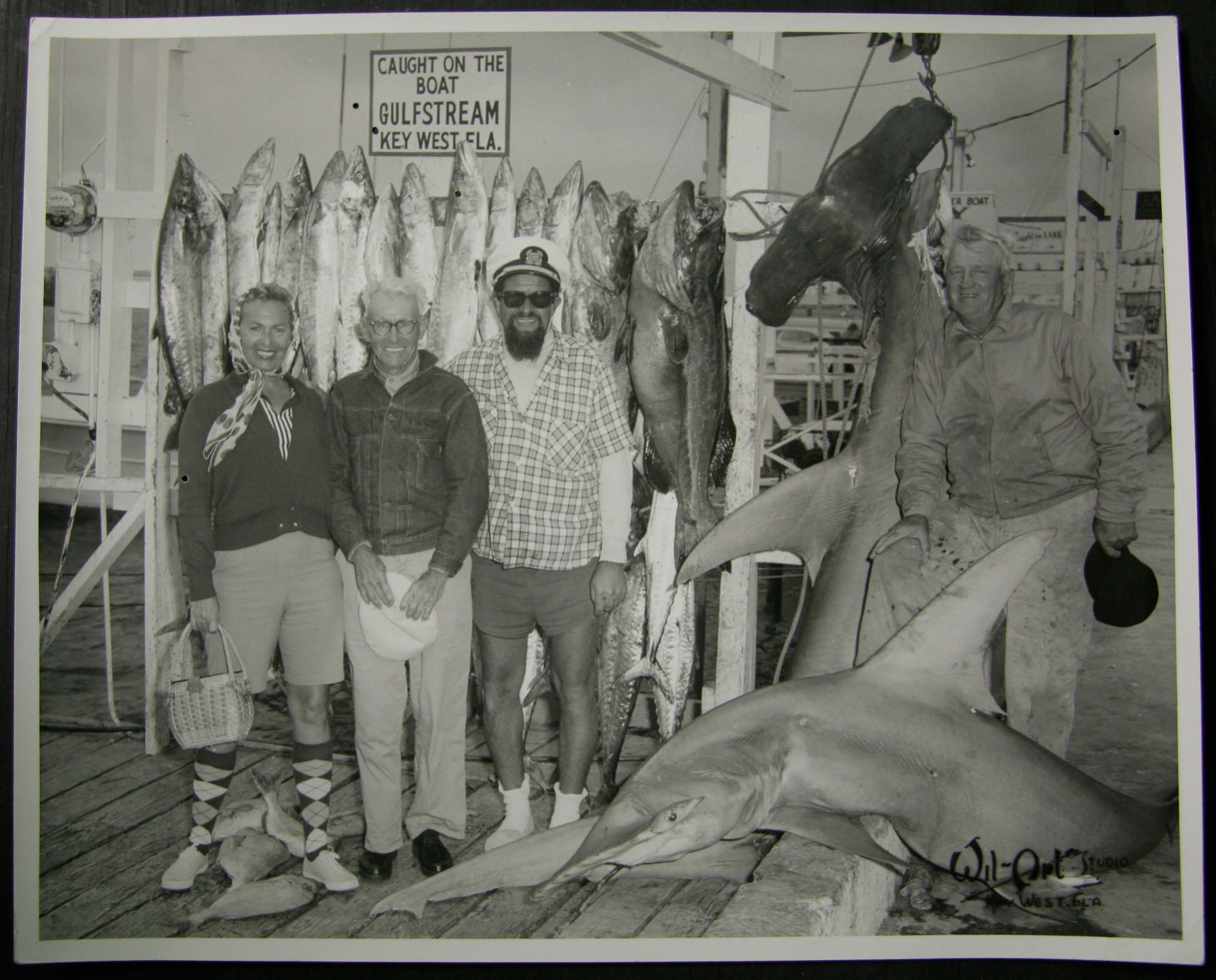

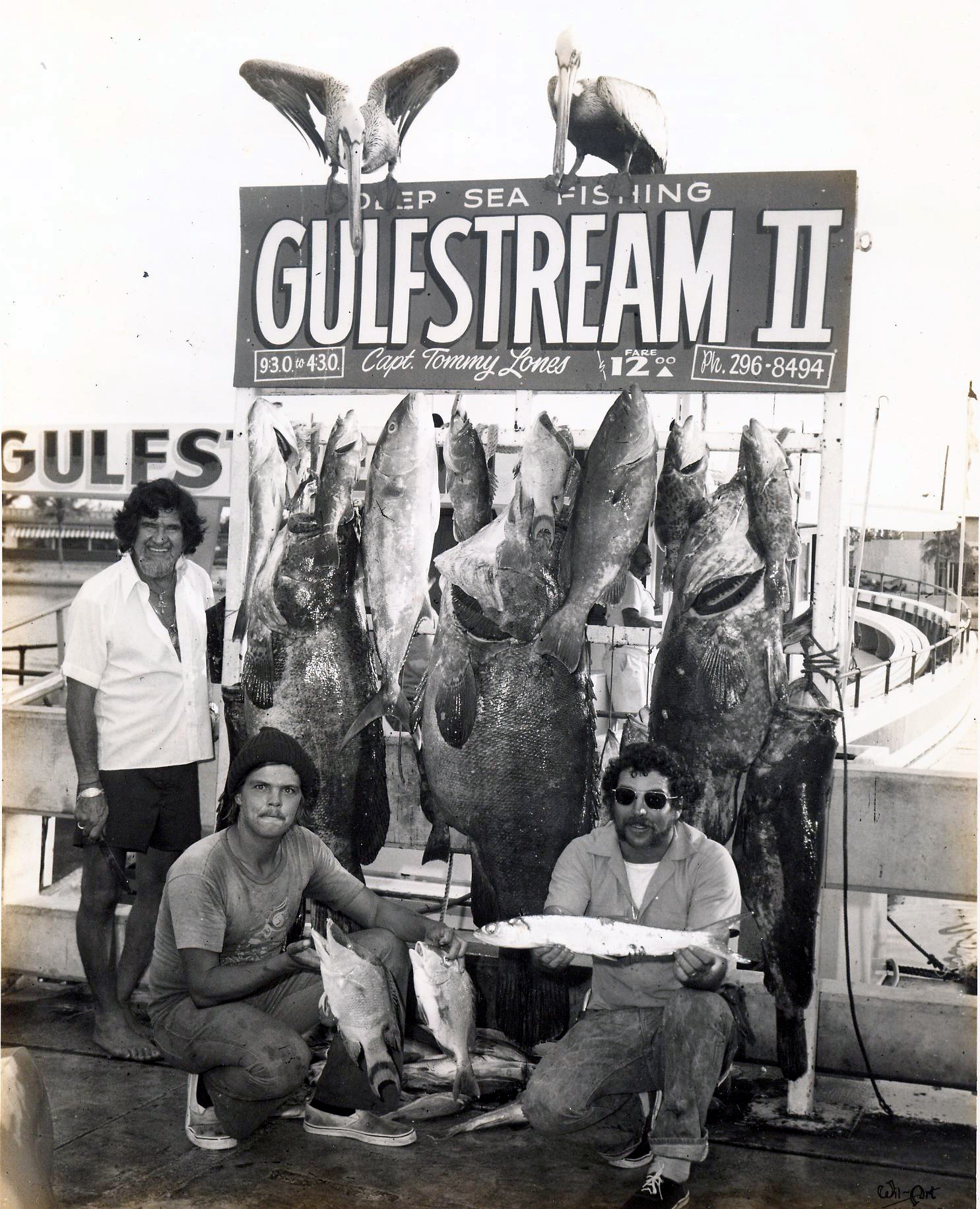

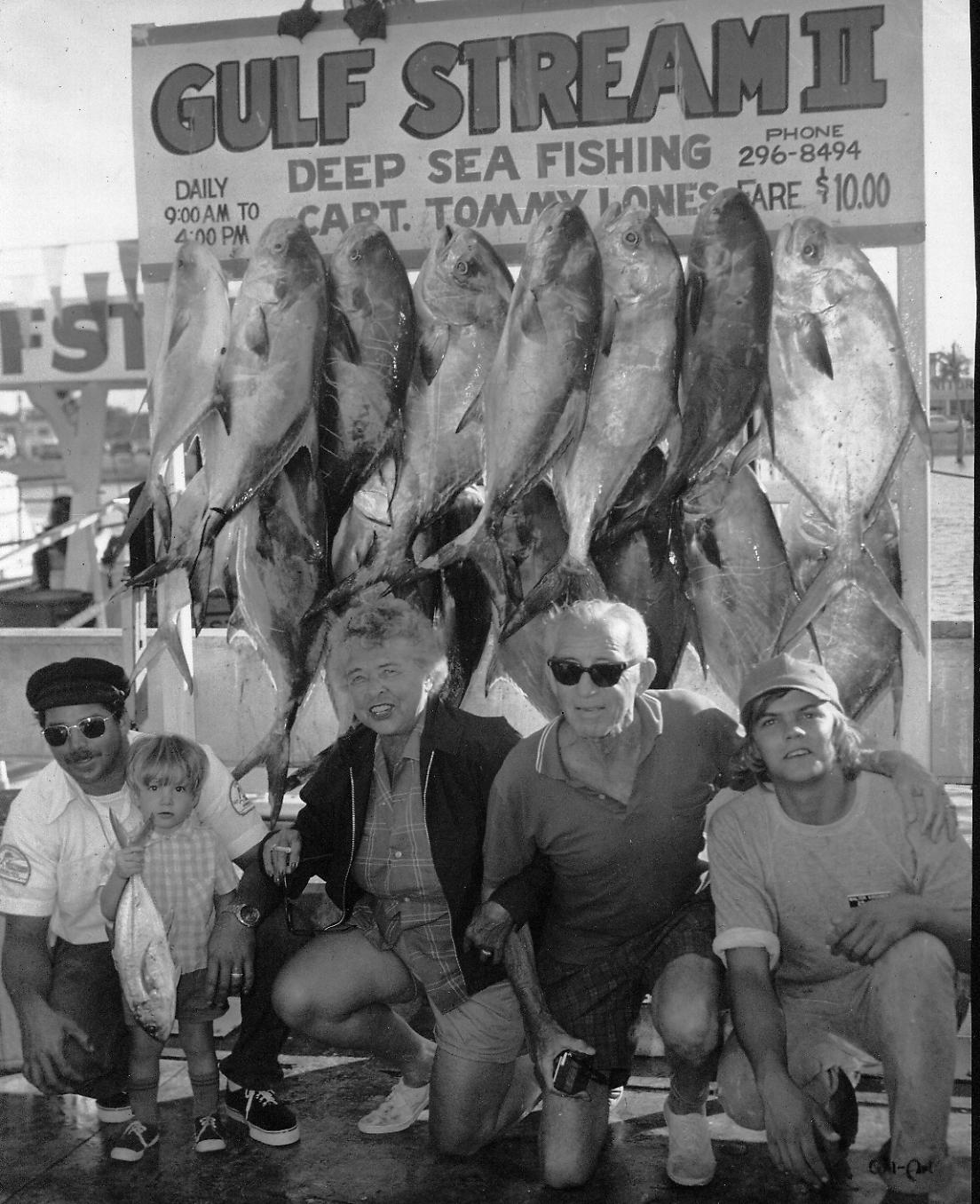

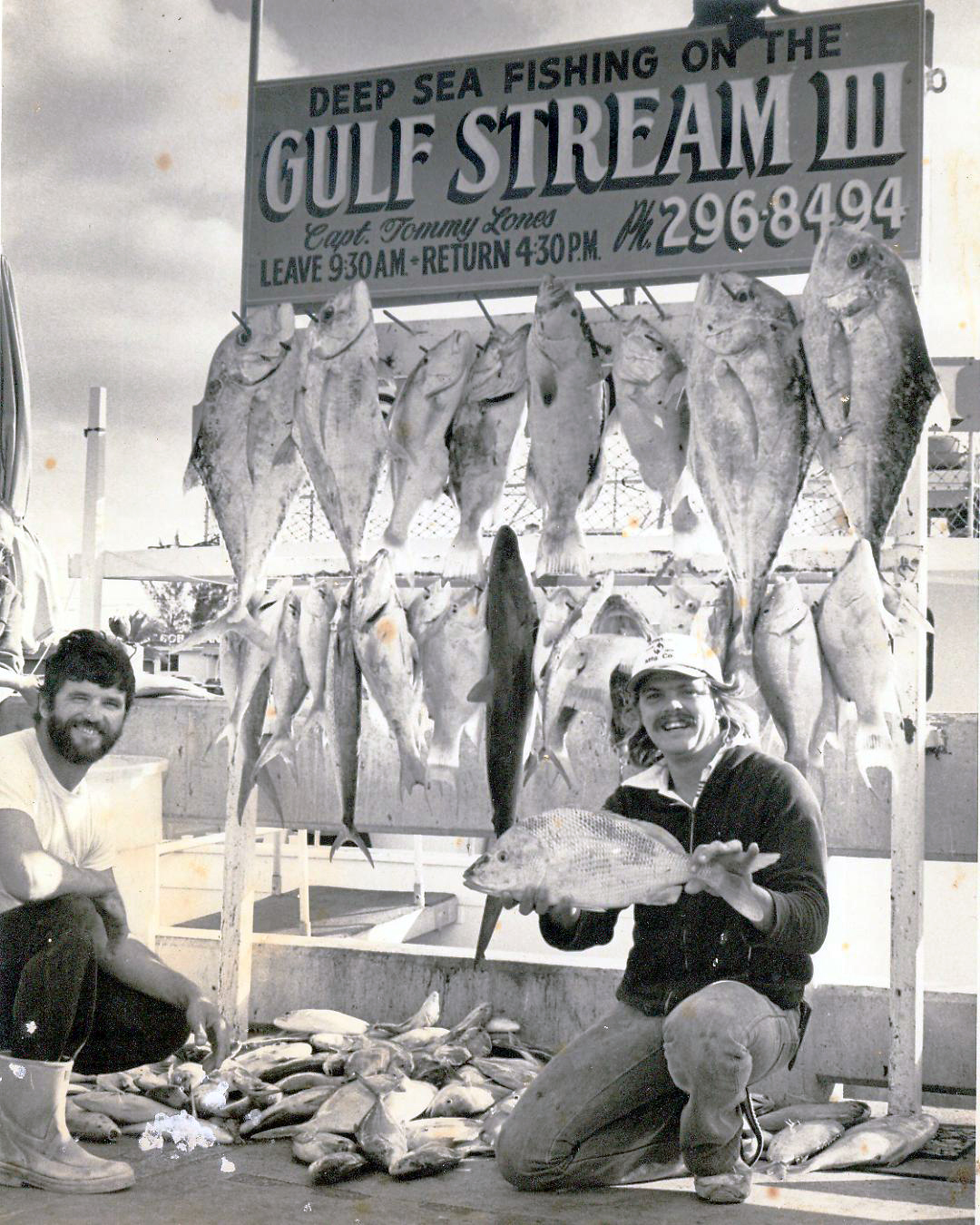

The recreational fishing docks of Key West, Fla., have seen many changes over the past 50 years. Boats change, captains change, and the clothes and hairstyles definitely change, but one thing remains same: People brag about what they catch and they take pictures to prove it really happened.

Today, these historical photographs of excited charter-boat passengers and their trophy fish — originally destined for vacation slideshows, family scrapbooks or office desk frames — are allowing Loren McClenachan to confirm scientifically what fathers and grandfathers have been preaching for years: Fish aren’t as big as they used to be.

In a study recently published in Conservation Biology, McClenachan, a graduate student at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, analyzed hundreds of trophy fish photographs taken in Key West since 1956. She found the average size of sport fish landings has declined substantially over five decades, likely as a result of overfished and damaged reef communities, and uncovered evidence that the ecosystems’ compositions increasingly are dominated by smaller fish species.

The loss of large fish species from the top of the food chain is dangerous — it can throw the system of checks maintaining these diverse ecosystems out of balance. A “second tier” fish species’ population that was once kept in check by a top predator can suddenly explode size and induce their predators’ numbers to collapse. These large swings in species composition eventually lead to an unstable, less diverse reef community more susceptible to environmental disturbance.

McClenachan spoke with Miller-McCune.com about her research on the loss of big species in Florida’s waters and its implications for future fishery conservation.

Miller-McCune: How did this project get started?

Loren McClenachan: Well, it’s part of my thesis, which is looking at long-term changes across ecosystems in the Caribbean. I’ve been looking at things like fish, but also turtles, monk seals, lobsters and corals, just to figure out how the ecosystem overall has changed over time. This is actually a 50-year study — and it’s actually a pretty short term study compared to some of my other projects, which have been on the order of 200 or 300 years — but the idea is that things have changed a lot and there hasn’t been a record of it in a lot of places because we depend on fisheries’ records. In places like the Caribbean, there are not always long-term records to show how things have changed, so going back and looking for other documents like photos, old diaries, even maps and things like that can provide some information that we really would not have otherwise.

M-M: Where did you get the photographs and how many did you use?

LM: I found the photographs at the Monroe County Library in Key West, which is a really small but really fantastic collection of documents related to Florida Keys history, and they had a ton of photos there. I found about 300 (photographs) in this collection.

M-M: I imagine there are a lot of things that can vary between photographs — people, places, distance from photographer, etc. So, how do you estimate and standardize the fish sizes?

LM: Well, I was really lucky with these photographs because they were all taken in the same spot. They were all taken at the Key West docks, which still exist, so I went down there and actually measured the heights of the hanging boards, which is what all the fish were displayed on at the end of the day. I had that as a constant, so then I just digitized the pictures, printed them out and just sat there, literally with a ruler, (doing) some really basic algebra to figure out the size of the fish relative to the hanging board. Of course if (the fish) were not visible all the way, I didn’t (include them). I only used fish that were able to be measured.

I was really lucky. A lot of the time you see pictures of dead fish that are sitting up in fish restaurants and things. That’s impressive, but it’s really hard to get anything quantifiable out of it because it’s hard to know how tall the person is who is holding it, and stuff like that. So, I was lucky to have that ruler built in to the pictures themselves.

M-M: Was there a problem determining the dates of the photographs?

LM: The earlier photographs actually had the dates printed on the back, which was really convenient, but for the later photographs, I had to end up (classifying) them into time periods rather than years. … I had to rely on the archivist in the library who knew basically when the captains changed on the boats. I was able to come up with three different time periods for the historical photos (1956-1960, 1965-1979 and 1980-1985).

(For comparison purposes, McClenachan herself took a series of photographs of the sport fishing landings at the Key West docks in 2007.)

M-M: Everyone knows a picture is worth a thousand words, so what are these pictures telling us?

LM: I think the pictures are telling us really clearly that the big fish that used to be abundant (in Florida’s waters) aren’t anymore and that’s happened really, really quickly. Over the course of a generation and a half, these big fish that used to be larger than the passengers themselves and were commonly caught just aren’t available anymore. I think that’s something that people instinctively know, but having the pictures to verify it is really helpful, especially since it (parallels) the old fish story — everyone says the fish used to be bigger, but these pictures actually show that in fact they really were.

M-M: So, there were shifts in species composition?

LM: Yes. This really isn’t a story about shifts in size within a particular species. I didn’t find that. What I did find is that the big species just aren’t there anymore. And I should say that some of them aren’t legal to be caught anymore, so they wouldn’t show in the landings. But the reason they are not legal to be caught anymore is because their populations are quite low. So, it’s really a shift from big, big species like goliath groupers and the big sharks to smaller things like (yellowtail) snappers, which are abundant, but they’re like 16 inches long (at their largest).

M-M: When I read your study, it reminded me of the “shifting baselines” problem in fisheries management. Can you explain what the concept of shifting baselines is?

LM: I think this is a classic case of shifting baselines, which is when people remember their childhood as being the natural state and the older you are, the wilder you think the world (once was). So, that has become built in to the fisheries management (and) into the minds of the managers themselves — they look to manage an ecosystem to become what they remember it as being natural. But often things changed a lot even before they came and saw the ecosystem. I think this is a classic example of that.

The thing that surprised me the most is that I went back and looked at the price that people were paying to go on these trips, and it hasn’t changed relative to income. People are still going out and paying the same amount to catch a 16-inch fish as they did to catch a fish that was bigger than they were, and they are still enjoying it — which you could say is great, but at the same time it’s kind of sad that people quickly forget that things used to be much, much better.

M-M: So, do you think then it’s more about the experience than what they are catching?

LM: Possibly, Possibly. Fishing trips are about more than catching just fish, but in the end it is still catching fish.

M-M: Give us an idea of what you think a “pristine” Florida ecosystem should be.

LM: I think the pictures clearly show that there used to be lots more big fish. That really jumps out. There used to be a lot of big animals, and we’re just not used to seeing that. I think that if you go to places like the middle of the Pacific where there hasn’t been fishing, you can see what a natural coral reef ecosystem could look like, and I think Florida did look like that not too long ago — just beyond the memories of people who are there now. … I don’t think the pristine ecosystem with a lot of big fish is really that distant of a memory that it couldn’t come back again.

M-M: What would it take for Florida to get these big fish back?

LM: I honestly don’t know the details of the management, but I would say that just closing more areas to fishing (is critical). There are already places that have been closed to fishing and within just a few years some of the big fish are beginning to come back. So, I would think that closing more areas to fishing and big enough areas so that it is ecologically significant is really an important part.

And then there’s also maintaining closures on fisheries. For example, the goliath grouper has been closed to fishing since 1990 and it’s starting to come back, which is great, which is fantastic. But without a long-term view of what the population used to be, people are already interested in opening the fishery again before the population really has recovered. I think really being vigilant in keeping fisheries closed and keeping more areas closed to fishing are the two big pieces of advice.

M-M: This clearly isn’t just a Florida issue. Can you, with any confidence, predict that if we could find photographs taken off the coast of California or anywhere else in the world, we would be seeing the same changes in fish species and size?

LM: I would say definitely. You would have to run the study to be 100 percent sure, but I think that anecdotally, yes. I think this is going on in Southern California, in New England and the Pacific Northwest — I think it’s going on everywhere. I think the decline in fisheries is universal, and the decline in big species is one of the most notable aspects about that. But I think one of the things that the photographs from this study are useful for is (underscoring that we need) to listen to the anecdotes. We’re not going to be able to have a case-by-case look in every area because the data might just not be there, but we really need to start listening to anecdotes of people who say, “There used to be a lot more fish here,” and wouldn’t be great if we could bring that back again without having to prove it in every place.

M-M: These photographs are sort of “above water” evidence that the ecosystems are changing, but what is the impact on the ecosystems when these big fish aren’t around?

LM: That’s a really good question. I think that big fish in general provide ecosystem stability. Having all this mass tied up in bigger, longer-living fish provides long-term stability to ecosystems that doesn’t tend to happen when the fish are smaller. (Now) there are shorter generation times in these populations, and those are more affected by fluctuations in the environment. Just in general, a whole ecosystem where you have a mix of small and big fish is generally more stable and desirable for diving and other things.

M-M: Part of the reason there has been a worldwide decline in fishery stocks over the last decade is because of the huge demand for fish and the big commercial fishing industry. Is there a way in your mind to bring this demand down?

LM: Yeah, I should be really clear about that: I’m not blaming recreational fishermen. It’s clearly a combination of recreational and commercial, and in this case, it’s mostly commercial fishing. The recreational photos are really just a metric of the overall decline and, yes, that’s on everybody’s shoulders. It is the increasing demand for fish, and I think things like sustainable aquaculture really need to be looked into more closely. There’s just not enough wild fish in the ocean to sustain the world’s population, and there’s really no easy answers to that (problem).

M-M: What other research are you working on and what other trends are you seeing?

LM: Well, I’ve been working mostly in the Florida Keys recently looking at (ecosystems) on a longer timescales, actually starting in the 1760s. I’m looking at changes in the actual structure in the environments — the corals, the mangroves and sponges, even all the way up to monk seals, which are extinct now. The sad thing is that everywhere I’ve looked, I’ve seen decline — everywhere from the spiny lobsters to the corals have declined quite a bit.

M-M: Any bright spots?

LM: Uh … actually none are really coming to mind. It’s kind of a depressing line of work when you’re looking at declines (laughs). … I think one of the things I say when I try to put an optimistic spin on it is that it provides a view of what things could be like. Yes, over the course of 300 years I found declines that probably aren’t fixable, but over the course of 50 years, it’s not so long that we couldn’t fix it if we wanted to. But I would say most of the bright spots don’t come from my work, they come from research looking at effects of protecting areas. … My job is just to show how bad things have gotten and hopefully we can swing things around. But (my results) do provide baselines for restoration — if the desire is there to do that.

Sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Are you on Facebook? Become our fan.