Between Baton Rouge and and New Orleans, there’s an 85-mile ribbon of land known as Cancer Alley. The uninviting nickname arose thanks to the large number of industrial plants that are clustered along this stretch of the Mississippi River.

Residents of the area blame this heavy industrial activity for releasing toxins that are making them sick. Around one nearby plant, the Environmental Protection Agency’s National Air Toxics Assessment has found that cancer risk is 700 times above the national average.

The burden falls particularly heavily on African Americans. Studies have shown that Cancer Alley’s polluting facilities are located in the areas with the highest percentage of black people. It’s a pattern that repeats itself across America: Communities of color, often living in poverty, are forced to sacrifice their health because they are tied to areas polluted by industrial development.

It’s a bitter pill to swallow, and one that has typically been sugarcoated by the conventional wisdom that new factories will bring jobs and economic development to deprived areas. This was the excuse I found being repeated by Hilco, a redevelopment company, when I reported on their plans to build a polluting logistics facility in the midst of a deprived Hispanic community in Chicago earlier this year. It’s also been exemplified by President Donald Trump’s promise to bring back coal and restore mining jobs, regardless of the negative effects on workers’ health, air quality, and climate change.

James Boyce, professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts–Amherst, found himself questioning this claim in March of 2001 while visiting communities in Cancer Alley for an unrelated research project. It was during a stopover in White Castle, a town bordered by a sugar factory and a Shell oil field, that one member of Boyce’s group asked the residents about the potential benefits of living in the shadow of industry.

“We don’t get anything,” said one White Castle resident.

“Some of the folks here at least work in the plants, right?” replied the member of the group.

“No, the jobs all go to white guys who drive in from elsewhere in pick-up trucks,” the resident responded.

This brief exchange set Boyce’s skepticism into gear. “It’s part of the reason we were always intrigued by this issue of where the jobs go, compared to where the pollution goes,” he says, 17 years later, and with a newly published academic paper on the topic to his name. “That’s what prompted us to do the digging, to collect all the data and do all the work.”

Boyce teamed up with Michael Ash, another economist at the University of Massachusetts–Amherst, to empirically investigate his suspicions that the promise of a jobs-environment tradeoff wasn’t everything it seemed. The two academics expanded the scope of their research beyond its Louisiana roots, collecting data on the top 1,000 polluting facilities in the United States that together generate 95 percent of the human health risk from industrial air toxics in the country.

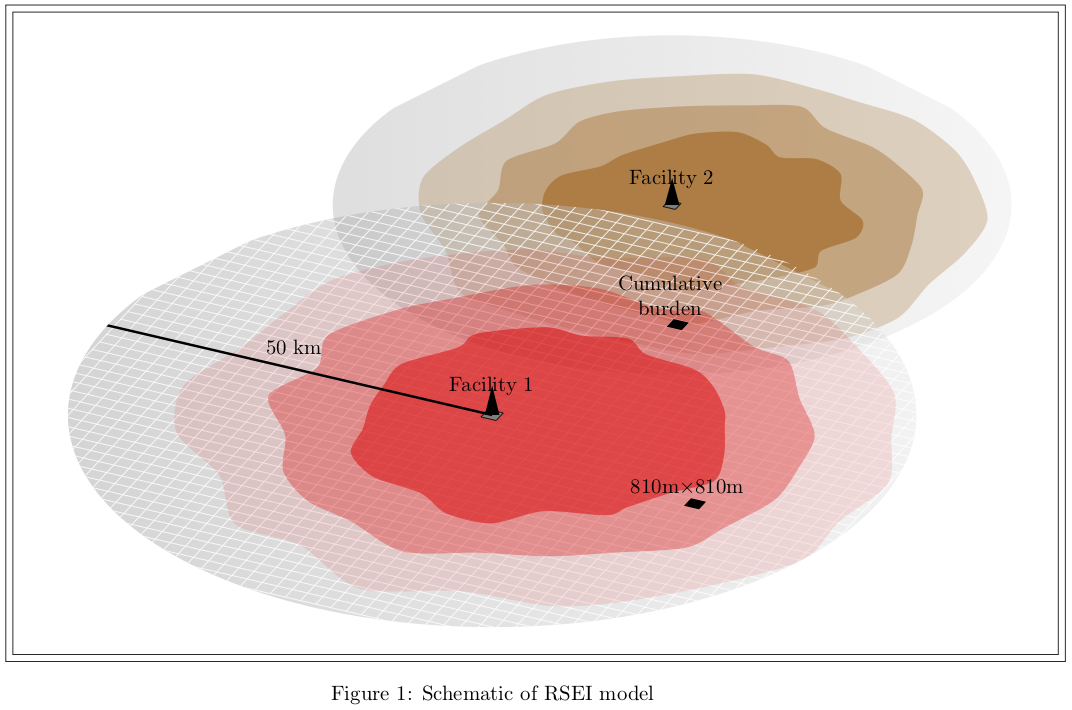

Pollution from a factory doesn’t fall equally on the surrounding community. The proportion of air toxics distributed on the nearby area depends not only on distance from the facility, but also on the height of the smokestacks, wind direction, and the velocity at which the gases are emitted. Rather than an indiscriminate circle drawn around the facility, the most burdened areas tend to be located inside an oval shape, flowing west to east from the facility.

(Photo: Michael Ash)

The economists then compared the data on the most polluted areas with confidential data from the Department of Labor, showing employment statistics by race, sex, and type of job.

“If you lived in a hypothetical state without discrimination, you’d expect the share of the risks and the share of the jobs to be roughly the same,” Ash says. “If the area around the facility is about 30 percent minority, you might expect about 30 percent of the risk to befall minorities and about 30 percent of the jobs to go to minorities.”

But that wasn’t the case. In fact, what they found broadly correlated with the observation made by the White Castle resident almost two decades ago: People of color were receiving a larger share of the pollution than of the available jobs.

Black people, on average, received 17.4 percent of the exposure, compared to just 10.8 percent of the jobs. At 312 facilities across the country, the share of pollution to which black people were exposed was double the share of jobs they received; the reverse was true at only 40 facilities. For high-quality jobs, the gap was even wider. The disparity was starkest in oil and coal manufacturing, where black and Hispanic people received 48 percent of the pollution exposure and just 22 percent of the jobs.

In other words, vulnerable communities of color living in the shadow of U.S. industry tend to suffer more than they gain. And the actual disparity could be worse, as the people of color who are employed by the facilities may not actually live in the worst-affected areas.

That means that, rather than providing jobs to the communities of color who are most acutely affected by the resulting air pollution, employment opportunities are instead going to white communities around the plant, or to commuters who live outside the 50-kilometer radius of the facility.

But Ash is quick to warn that it isn’t a zero-sum game: Their study doesn’t reveal winners so much as the greatest losers.

“It’s not necessarily that someone is gaining, because that [environmental] burden also befalls white people living in the area where pollution falls from the facility,” Ash says. “It does suggest that there is a profound lack of economic return or benefit to communities of color who are living strongly exposed. But I do not think it should be seen as a clear displacement.”

Either way, this research should make anyone facing the supposed choice between clean air and a good job think twice. Sometimes, there isn’t really a choice at all.

New Landscapes is a regular series investigating how environmental policies are affecting communities across America.