The population of Wamsutter, Wyoming may have grown four times over in the last three years, but the town on the southeastern edges of some of the largest natural gas fields on the continent is still a dusty pit stop off Interstate 80. The augmented volume of trucks flowing through this isolated interchange only affirms the energy boom of the Intermountain West—and the fracturing of the habitat of the American pronghorn.

Once ubiquitous on the Great Plains and high deserts of the American West, these antelope rely on thousands of miles of unspoiled ranges to avoid their predators, and to find food in winter. Galloping pronghorns—which stand about three feet high at the shoulder and weigh less than 125 pounds—can reach Interstate speeds of 60 to 70 miles per hour. Now, natural gas development, mostly on Bureau of Land Management territory in Vermont-sized counties like Sweetwater or the smaller Sublette in the western half of the state, have crowded the animals’ room to run.

A study led by the Bronx-based Wildlife Conservation Society, reported in the journal Biological Conservation, links the fervid development of two of the country’s largest gas fields to the abandoning of the area by the pronghorn. Those two fields, the Pinedale Anticline and the Jonah, lie in the southern region of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem—right in the middle of the pronghorn’s winter range.

Tens of millions of pronghorn once roamed North America; 700,000 remain, with more than half in Wyoming. “They are open country animals that have to see their threats and escape by running. They’re vulnerable to predators like coyotes, wolves, and mountain lions,” explains Jackie Skaggs, a public affairs officer at Grand Teton National Park.

Pronghorn graze in sight of natural gas derricks in the Upper Green River Basin , Wyoming. (Photo by Jeff Burrell, Wyoming Conservation Society)

In winter, the animals need large expanses with shallow snow, so they can find sagebrush to eat. Roaming the desert based on snow depth and wind direction, pronghorn will go as far south as Green River, Wyoming, some 200 miles south of the Tetons. Aside from migration bottlenecks created by a couple of natural pinch points and some private property fencing, the Wyoming pronghorn remain fairly unimpeded until they hit the gas fields, in the southwestern part of the state, which lie smack in the middle of their winter ranges.

“Because of human occupation, roads, development, fence lines, and cattle grazing,” said Skaggs, “the free flow of pronghorn … has been greatly restricted.”

Researchers have long noted that the fracking sites interfered with the pronghorn’s 6,500-year-old migration routes. For the Wildlife Conservation study, 125 female pronghorn were tracked using GPS over five years. In that time, says Jon Beckmann, scientist for the Wildlife Conservation Society’s North America program and the study’s lead author, natural gas field development in the Upper Green River basin has led to pronghorn abandoning up to 82 percent of their highest quality winter range.

“We’re not seeing changes in mortality or reproduction of the pronghorn due to the gas fields,” said Renee Seidler, a field biologist at the Wildlife Conservation Society. “But we’re seeing the beginnings of problems for the pronghorn and the winter range,” describing a trajectory already seen among the region’s mule deer.

If the gas fields were static, she adds, the pronghorn would likely adapt, but the fields are expanding.

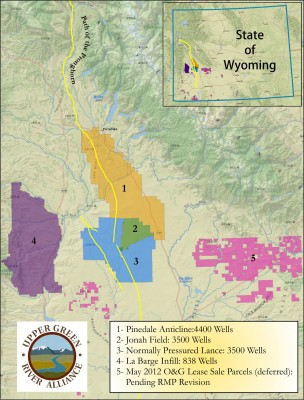

The intersection of ancient pronghorn migration routes and modern-day gas fields. Click to enlarge (Map from Linda F. Baker, Upper Green River Alliance)

“We started with 45 gas wells in the Jonah field and now there are 4,500 permitted wells,” says Linda Baker, the director of the Upper Green River Alliance in Pinedale, Wyoming,, adding that 4,400 wells are permitted on the Pinedale Anticline, and the undrilled field over will be permitted for 3,500 wells.

Jon Beckmann says development in the Upper Green River basin could be done with consideration for the wildlife, with a permeable landscape for migration and the density of the wells kept below certain numbers in important pronghorn wintering areas.

Most of the 60,000 pronghorn that make up the herd in Sublette County just south of the Tetons, migrate to other summer ranges throughout the western part of the state. “The pronghorn that summer in the Grand Tetons are tied to those wintering areas where the natural gas drilling is occurring,” said Steve Cain, a senior wildlife biologist at the park. Only some 200 to 400 pronghorn migrate as far north as Jackson Hole and Grand Teton National Park itself. “If there are large impacts on the wintering range, the population in the park could actually go extinct.”