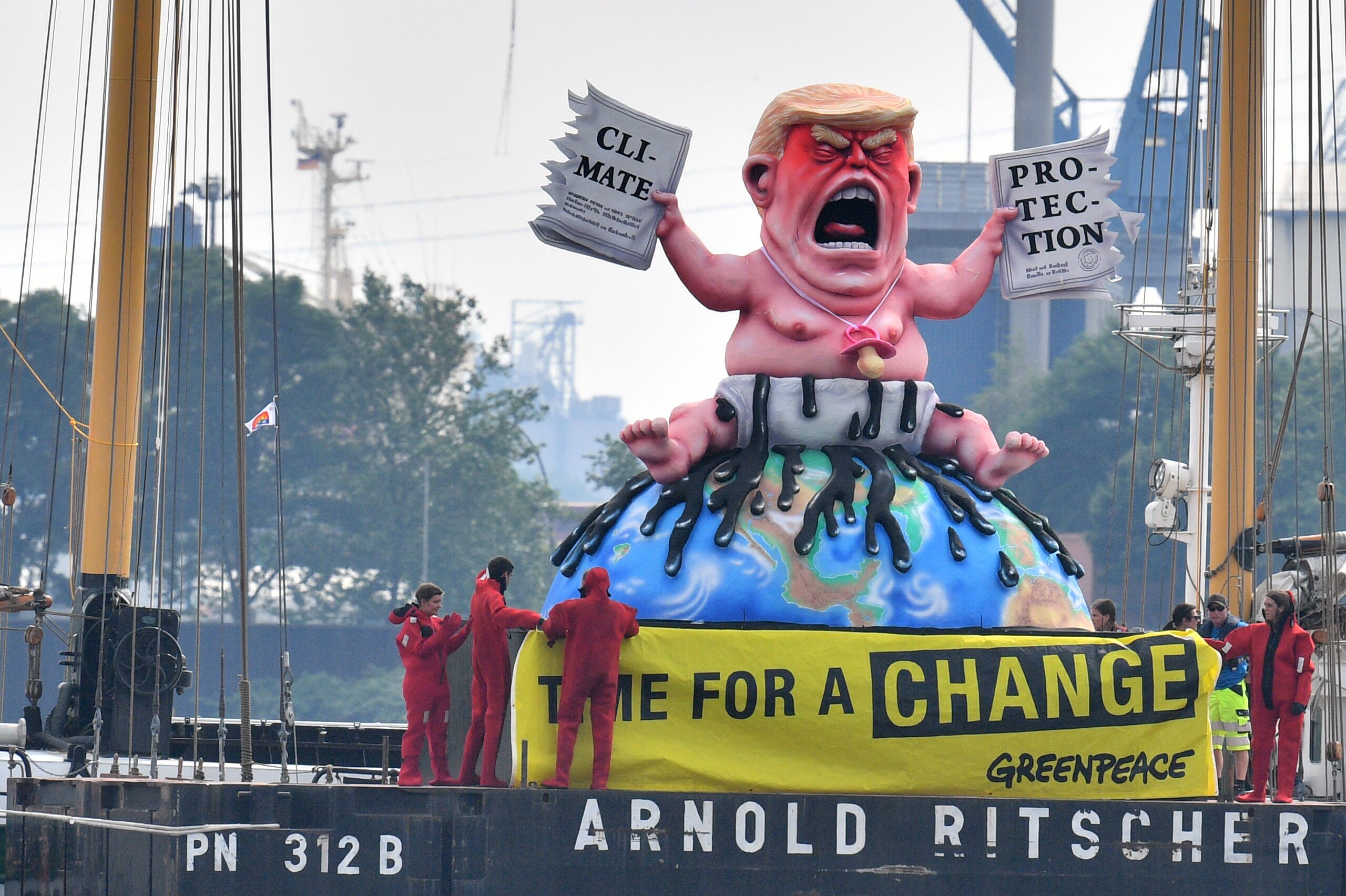

(Photo: Ukas Michael/Getty Images)

The United States’ approach to global climate policy under President Donald Trump has become a little more clear after the Group of 20 meeting in Hamburg, Germany. Trump’s infamous withdrawal from the Paris climate agreement was framed as a way of getting a better deal for the U.S. In talks leading up to the Hamburg G20 summit, American diplomats fleshed out Trump’s bid.

“The signal I got from German negotiators is that the U.S. doesn’t really want to pull out, it wants to renegotiate the Paris Agreement,” says Brigitte Knopf, secretary general of the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change, an influential German think tank.

Even as the other 19 countries in the G20 bloc declared the Paris Agreement irreversible, U.S. officials pushed for three specific concessions: a ratcheting-down mechanism that would formally enable countries to reduce their pledges; changes to the language on climate financing; and a broader definition of clean energy that can encompass fossil fuels.

The U.S. stance on the first two points was puzzling to some European climate policy analysts. The Paris Agreement already includes mechanisms for changing emissions pledges, and it doesn’t include any legally binding sanctions regarding climate financing, according to climate economist Reimund Schwarze, with the Helmholtz Center for Environmental Research in Leipzig, Germany.

But the U.S. enjoyed surprising success in bringing an “old-fashioned, fossil fuel-based, energy independence” message to the table at the G20 meeting, Schwarze says, crediting Everett Eissenstat, the Trump administration’s newly appointed lead negotiator for summits on trade and economic issues.

“It was an effective effort. It was scary how successful he was with such a risky strategy,” Schwarze says. “I would have bet three weeks ago U.S. strategy would result in a tremendous isolation, but [Eissenstat] was able to get it on the table, and he found some supporters, not only in Poland.”

As a result, the G20 communiqué includes language aimed at acknowledging U.S. efforts to help other countries “access and use fossil fuels more cleanly and efficiently.” Not everyone was happy with that phrase, but it does leave wiggle room for other countries who might be wavering over their commitments.

How that will play out is unclear, but it seems to be part of Trump’s emerging strategy of trying to boost U.S. exports of natural gas, says Schwarze, adding that any fossil-fuel detours will deviate from the most direct path to the targets of the Paris Agreement.

“If Trump has an energy policy, it’s about making the U.S. the biggest energy producer in the world, and natural gas is central to that strategy,” Schwarze says.

(Photo: Boris Roessler/AFP/Getty Images)

AMERICA WILL STAY INVOLVED WITH PARIS NEGOTIATIONS

In some ways, the outcome of the G20 summit reaffirms the resilience of the global climate policy framework, especially the Paris Agreement, which may be straining following U.S. withdrawal but doesn’t appear in danger of breaking.

And for now, American diplomats are still involved in critical aspects of global climate talks relating to implementation of the Paris Agreement, according to Andrew Light, who was part of President Barack Obama’s climate strategy team and is now a senior fellow at the World Resources Institute.

“The U.S. is still sitting as co-chair of the working group on transparency,” Light says. Transparency is key to implementing the Paris Agreement because the commitments countries have made are only as strong as the world’s ability to accurately track progress toward those targets.

“The U.S. negotiators have some of the best ideas in the room on some of these critical issues, especially on transparency, but they are in a tough spot. The pressure is on these guys,” Light says, explaining that every move by American climate diplomats will face an extra measure of scrutiny from other countries who are well aware of the administration’s stated hostility to the Paris Agreement.

Even with the 3.5-year withdrawal process underway, American negotiators will apparently stay at the table for now. But Trump’s stance has hindered climate diplomacy in other areas. Leaders from other countries have come through the White House without mentioning climate change because they are trying to work out deals on other issues like security and trade, Light says.

He contrasts the current situation to the Bush era, when there were high-level officials with the Department of Energy and other agencies still pushing for ways for the U.S. to remain involved despite the administration’s skepticism.

“The people in the Trump administration are in a much more difficult position, when you don’t know what the boss is going to say from one day to another,” he says.

Light hopes a carbon tax being promoted by U.S. businesses and a group of prominent GOP elders will find political traction in the next few years. It doesn’t seem likely that such a policy could find widespread favor in the current ideological climate, but the ground could be prepared for the time when the political equation in the U.S. changes. Depending on how it’s structured, a carbon tax could be more effective in reducing greenhouse gas emissions than Obama’s policies, according to research by the World Resources Institute.

THE G20 ACTION PLAN

According to Knopf, the G20 meeting marked a critical point in global climate diplomacy, at which any other wavering countries—potentially Saudi Arabia or Russia—could have widened the Trump rift. But that didn’t happen.

“Now, the opportunity for other countries to step out or criticize [the Paris agreement] is past,” Knopf says, adding that the rest of the world is moving beyond any fundamental debates about global climate goals to the process of implementing the Paris Agreement.

That was reflected by the unanimous adoption of the Climate and Energy Action Plan for Growth, which is perhaps more important than the general G20 communiqué, according to Knopf. Even while media coverage didn’t emphasize the action plan, Knopf insists it’s a critical document going forward, linking climate and energy more closely than ever before, at the urging of the German environment ministry.

The action plan commits G20 countries to scale up investments in renewable energy and to funding climate adaptation measures in less developed countries. It’s based on the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals that include ambitious targets like eradicating hunger and poverty. Knopf says that, aside from the U.S., there is consensus to redirect investment flows away from fossil fuels. Carbon pricing is also part of the action plan, with the expectation for progress at two autumn climate summits outside the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change.

Other climate policy experts warn that the U.S. reversal on Paris could still have serious consequences. The longer the Trump regime lasts, the higher the risk of a new divide, says Susanne Dröge, a policy expert with the German Institute for International and Security Affairs.

“Cracks were always there and were covered by the new approach taken under the Paris Agreement. Now that the U.S. withdraws its commitment and money, this is an inroad for those who were skeptical about the Paris deal anyway,” Dröge says.