When Marc Reisner published his groundbreaking — and self-proclaimed apocalyptic — analysis of the West’s water woes in 1986, geographic information systems were in their infancy and climate forecasting models could take months to run. Not that Reisner’s predictions in Cadillac Desert: The American West and its Disappearing Water were without merit. Indeed, his concerns that water shortages would pit urban population growth against food production are fast becoming a reality.

At the time of publication, Reisner’s text wasn’t viewed as a scientific piece of work, but it did make people wake up to the problems of water use in the West — an issue applicable to other arid and semi-arid areas like Australia, parts of India, Pakistan, China, Mexico and Brazil.

Enter John Sabo, an Arizona State University professor specializing in risk assessment and statistical issues in ecology. After reading Cadillac Desert three years ago, Sabo was shocked to discover that no follow-up investigation of the text had been conducted.

“The big thing that struck me,” says Sabo, “is that you have this kind of picture of what the West looks like in terms of water, but there’s only one map in the whole book, even in the most recent printing.”

In 2008, Sabo decided the time was ripe to gather a group of experts to do an assessment — in time for the 25th anniversary of Reisner’s book. “Reclaiming freshwater sustainability in the Cadillac Desert,” published last December by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, employs cutting-edge science to investigate Reisner’s overarching concern: whether mismanagement of water resources and shortages will lead to the eventual collapse Western (U.S.) civilization.

More specifically, Sabo analyzed Reisner’s three main “apocalypses”:

• Sediment will reduce the capacity of reservoirs leading to unprecedented scarcity.

• Soils will become degraded thanks to increasing salinity disrupting the farmlands so vital to the West and the rest of the U.S.

• Increasing population in urban areas will displace water from agriculture, limiting food availability.

And while Sabo thinks the term apocalypse is overstated, he believes Reisner accurately depicted “region-wide hydrologic dysfunction” in the West. “In many ways,” says Sabo, “Reisner was visionary.” And that was before widespread knowledge about climate change reshuffled the cards.

The late journalist’s insights and analysis extend to the mid-19th century, when “Go West, young man” echoed through the urbanizing East. Back then, Los Angeles had fewer than 2,000 people, and Denver barely existed. But the now-iconic call to action was followed by an equally transformative, if lesser-known maxim, “Rain follows the plow,” a cultish belief inspired by a mere coincidence. For in a key period of those heady days of relentless western expansion, the so-called Great American Desert was soaked by uncharacteristic rainfall, prompting many to attribute the increased moisture to the building of towns, creation of mines and plowing of land.

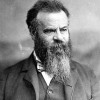

As Reisner points out, not everyone at that time believed in some divine spigot. Most notable was John Wesley Powell, the consummate frontiersman and renaissance man, who learned about the West’s flora, fauna and hydrology from intimate contact with the land. Though he lost his right arm in the U.S. Civil War’s Battle of Shiloh, Powell led geographic expeditions of the Colorado River in 1869 and 1871, treks that culminated in The Report on the Lands of the Arid Regions of the United States, published by the U.S. government.

Three-Part Series

This is the first part of a three-part series looking at the legacy of the groundbreaking story of water use and abuse in the Western United States, “Cadillac Desert”:

Part I — Greening the Desert? Not So Fast!

Part II — Water Shortages Threaten the American West Lifestyle

Part III — Solutions to Water Supply Woes Surface in the West

Known as “Powell’s Prophecy,” the study offered a startling prediction: If you took all the surface water flowing between the Columbia River and the Gulf of Mexico and spread it out evenly, you’d still have a desert.

“Powell made various proclamations about how much water it would take to irrigate the available arable land in the Western U.S. — all done on horse. Historians will say he’s off by this or that much, but still, he’s pretty close,” Sabo says.

The study’s prediction was largely ignored by Congress, at the time, and fervent believers in manifest destiny — the notion that western development was a God-given right. It was ignored right through the 1950s, when the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation set about greening the desert. It’s being ignored to the present day.

But beyond such inconvenient theories, the second director of the U.S. Geological Survey also published numerous independent articles detailing suggestions for coping with the region’s persistent drought. Most significant, according to Charles Hutchinson, a geographer specializing in remote sensing and arid lands, Powell espoused two revolutionary views concerning land management and water use. Writing in the 2000 Cosmos Journal (a publication of the Cosmos Club, itself founded in Powell’s parlor in 1878), Hutchinson explained Powell’s belief that land units should be organized around watersheds rather than the “survey system that imposed a rigid systematic grid pattern on the land.”

Moreover, Hutchinson says Powell envisioned irrigation issues as supremely contentious and believed in “watershed commonwealths” developed by communities rather than individual efforts.

“This,” wrote Hutchinson, “was a significant departure from the Jeffersonian ideal of democracy based on individual independent farmers that had helped propel westward expansion.”

Unsurprisingly, Reisner wrote, rail companies and speculators looking to profit from large-scale development and industrial-sized farms undermined these suggestions. Ironically though, following Powell’s predicted droughts — which occurred in the 1890s and 1930s, “…the irrigation program Powell had wanted became a monster, redoubling its efforts and increasing its wreckage, both natural and economic, as it lost sight of its goal.”

No doubt, Cadillac Desert served as a wake-up call to the water scarcity issue in the West. Unfortunately, many of us are still hitting the snooze button.

In the second part of this series, bad policy decisions and wasteful living patterns amplify the built-in concerns over greening a desert.

Sign up for the free Miller-McCune.com e-newsletter.

“Like” Miller-McCune on Facebook.

Follow Miller-McCune on Twitter.

Add Miller-McCune.com news to your site.