In his most recent State of the Union address, President Obama touted “more oil produced at home than we buy from the rest of the world—the first time that’s happened in nearly 20 years.” It’s true: U.S. crude oil production has increased from about five million barrels per day to nearly 7.75 mb/d over the past five years (we still import over 7.5 mb/d). And American natural gas production is at an all-time high.

But there’s a problem. We’re focusing too much on gross numbers. (The definition of gross I have in mind is “exclusive of deductions,” as in gross profits versus net profits., though other definitions apply here, too.) While these gross numbers appear splendid, when you look at net, things go pear-shaped, as the British say.

Our economy is 100 percent dependent on energy: With more and cheaper energy, the economy booms; With less and costlier energy, the economy wilts. When the electricity grid goes down or the gasoline pumps run dry, the economy simply stops in its tracks.

With money as with energy, we are doing extremely well at keeping up appearances by characterizing our situation with a few cherry-picked numbers. But behind the jolly statistics lurks a menacing reality.

But the situation is actually a bit more complicated, because it takes energy to get energy. It takes diesel fuel to drill oil wells; It takes electricity to build solar panels. The energy that’s left over—once we’ve fueled the production of energy—makes possible all the things people want and need to do. It’s net energy, not gross energy, that does society’s work.

Before the advent of fossil fuels, agriculture was our main energy source, and the average net gain from the work of energy production was minimal. Farmers grew food for people—who did a lot of manual work in those days—and also for horses and oxen, whose muscles provided motive power for farm machinery and for land transport via carts and carriages. Because margins were small, most people had to toil in the fields in order to produce enough surplus to enable a small minority to live in towns and specialize in arts and crafts (including statecraft and soldiery).

In contrast, the early years of the fossil fuel era saw astounding energy profits. Wildcat oil drillers could invest a few thousand dollars in equipment and drilling leases and, if they struck black gold, become millionaires almost overnight. (For a taste of what that was like, watch the classic 1940 film Boom Town, with Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert.)

Huge energy returns on both energy and financial investments in drilling made the fossil fuel revolution the biggest event in economic history. Suddenly society was awash with surplus energy. Cheap energy plus a little invention yielded mechanization. Farming became an increasingly mechanized (i.e., fossil-fueled) occupation, which meant fewer field laborers were needed. People left farms and moved to cities, where they got jobs on powered assembly lines manufacturing an explosively expanding array of consumer goods, including labor-saving (i.e., energy-consuming) home machinery like electric vacuum cleaners and clothes washers. Household machines helped free women to participate in the work force. The middle class mushroomed. Little Henry and Henrietta, whose grandparents spent their lives plowing, harvesting, cooking, and cleaning, could now contemplate careers as biologists, sculptors, heart specialists, bankers, concert violinists, professors of medieval French literature—whatever! Human ambition and aspiration appeared to know no bounds.

Unfortunately, there are a couple of problems with fossil fuels: They are finite in quantity and of variable quality. We have extracted them using the low-hanging fruit principle, going after the highest quality, cheapest-to-produce oil, coal, and natural gas first, and leaving the lower quality, more expensive, and harder-to-extract fuels for later. Now, it’s later.

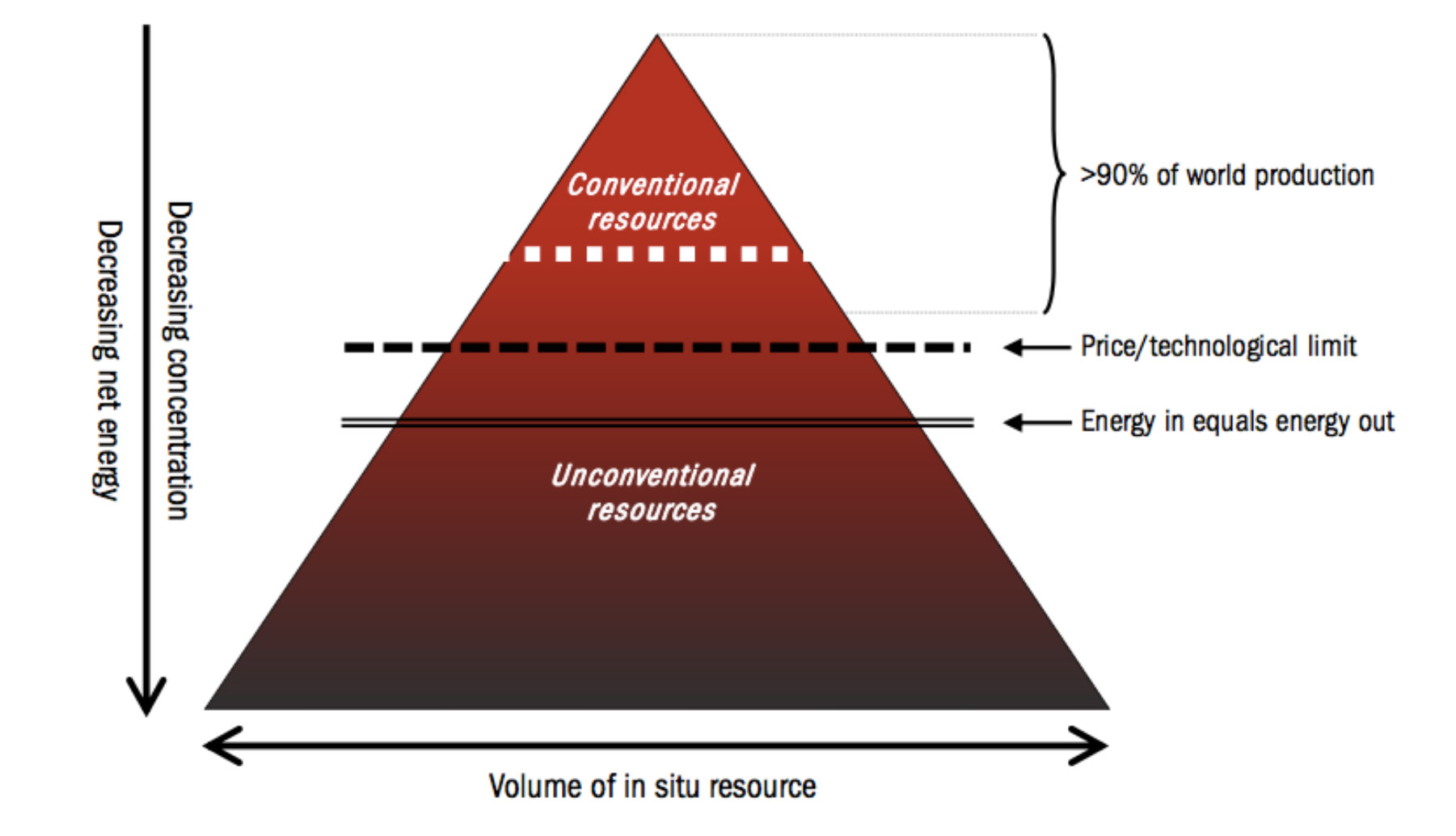

It’s helpful to visualize this best-first principle by way of a diagram of what geologists call the resource pyramid. Extractive industries typically start at the top of the pyramid and work their way down. This was the case historically when coal miners at the beginning of the industrial revolution exploited only the very best coal seams, and it’s also true today as tight oil drillers in places like North Dakota concentrate their efforts in core areas where per-well production rates are highest.

We’ll never run out of any fossil fuel, in the sense of extracting every last molecule of coal, oil, or gas. Long before we get to that point, we will confront the dreaded double line in the diagram, labeled “energy in equals energy out.” At that stage, it will cost as much energy to find, pump, transport, and process a barrel of oil as the oil’s refined products will yield when burned in even the most perfectly efficient engine.

As we approach the energy break-even point, we can expect the requirement for ever-higher levels of investment in exploration and production on the part of the petroleum industry; We can therefore anticipate higher prices for finished fuels. Incidentally, we can also expect more environmental risk and damage from the process of fuel “production” (i.e., extraction and processing), because we will be drilling deeper and going to the ends of the Earth to find the last remaining deposits, and we will be burning ever-dirtier fuels.

That’s exactly what is happening right now.

Our economy is 100 percent dependent on energy: With more and cheaper energy, the economy booms; With less and costlier energy, the economy wilts.

WHILE AMERICA’S CURRENT GROSS oil production numbers appear rosy, from an energy accounting perspective the figures are frightening: Energy profit margins are declining fast.

Each year, a greater percentage of U.S. oil production comes from unconventional sources—primarily tight oil and deepwater oil.Compared to conventional oil from most onshore, vertical wells, these sources demand much higher capital investment per barrel produced. Tight oil wells typically require directional drilling and fracking, which take lots of money and energy (not to mention water); Initial production rates per well are modest, and production from each tends to decline quickly. Therefore, more wells have to be drilled just to maintain a constant rate of flow. This has been called the “Red Queen” syndrome, after a passage in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass.

In Carroll’s story, the fictional Red Queen runs at top speed but never gets anywhere. “It takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place,” she explains to Alice. Similarly, it will soon take all the drilling the industry can do just to keep production in the fracking fields steady. But the plateau won’t last; As the best drilling areas become saturated with wells and companies are forced toward the periphery of fuel-bearing geological formations, costs will rise and production will fall. When, exactly, will the decline begin? Probably before the end of this decade.

Deepwater production is expensive, too. It involves operating in miles of ocean water on giant drilling and production rigs. Deepwater drilling is also both environmentally and financially risky, as BP—and the rest of us—discovered in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010.

America is turning increasingly to unconventional oil because conventional sources of petroleum are drying up—fast. The United States is where the oil business started and, in the past century-and-a-half, more oil wells have been drilled here than in the rest of the world’s countries put together. In terms of our resource pyramid diagram, the U.S. has drilled through the top “conventional resources” triangle and down to the thick dotted line labeled “price/technology limit.” At this point, new technology is required to extract more oil, and this comes at a higher financial cost not just to the industry, but ultimately to society as a whole. Yet society cannot afford oil that’s arbitrarily expensive: The “price/technology limit” is moveable up to a point, but we may be reaching the frontiers of affordability.

Trans-Alaska Oil Pipeline. (Photo: Alberto Loyo/Shutterstock)

Lower energy profits from unconventional oil inevitably show up in the financials of oil companies. Between 1998 and 2005, the industry invested $1.5 trillion in exploration and production, and this investment yielded 8.6 million barrels per day in additional world oil production. But between 2005 and 2013, the industry spent $4 trillion on exploration and production, yet this more-than-doubled investment produced only 4 mb/d in added production.

It gets worse: All net new production during the 2005-13 period came from unconventional sources; of the $4 trillion spent, it took $350 billion to achieve a bump in production. Subtracting unconventionals from the total, world oil production actually fell by about a million barrels a day during these years. That means the oil industry spent over $3.5 trillion to achieve a decline in overall conventional production.

Last year was one of the worst ever for new discoveries, and companies are cutting exploration budgets. “It is becoming increasingly difficult to find new oil and gas, and in particular new oil,” Tim Dodson, the exploration chief of Statoil, the world’s top conventional explorer, recently told Reuters. “The discoveries tend to be somewhat smaller, more complex, more remote, so it is very difficult to see a reversal of that trend…. The industry at large will probably struggle going forward with reserve replacement.”

While America’s current gross oil production numbers appear rosy, from an energy accounting perspective the figures are frightening: Energy profit margins are declining fast.

The costs of oil exploration and production are currently rising at about 10.9 percent per year, according to Steve Kopits of the energy analytics firm Douglas-Westwood. This is squeezing the industry’s profit margins, since it’s getting ever harder to pass these costs on to consumers.

In 2010, The Economist magazine discussed rising costs of energy production, musing that “the direction of change seems clear. If the world were a giant company, its return on capital would be falling.”

Tim Morgan, formerly of the London-based brokerage Tullett Prebon (whose customers consist primarily of investment banks), explored the average Energy Return on Energy Investment (EROEI) of global energy sources in one of his company’s Strategy Insights reports, noting: “For 2020, our projected EROEI (of 11.5:1) [would] mean that the share of GDP absorbed by energy costs would have escalated to about 9.6 percent from around 6.7 percent today. Our projections further suggest that energy costs could absorb almost 15 percent of GDP (at an EROEI of 7.7:1) by 2030…. [T]he critical relationship between energy production and the energy cost of extraction is now deteriorating so rapidly that the economy as we have known it for more than two centuries is beginning to unravel.”

From an energy accounting perspective, the situation is in one respect actually worst in North America—which is deeply ironic: It’s here that production has grown most in the past five years, and it’s here that the industry is most boastful of its achievements. Yet the average energy profit ratio for U.S. oil production has fallen from 100:1 to 10:1, and the downward trend is accelerating as more and more oil comes from unconventional sources.

These profit ratios might be spectacular in the financial world, but in energy terms this is alarming. Everything we do in industrial societies—education, health care, research, manufacturing, transportation—requires energy. Unless our investment of energy in producing more energy yields an average profit ratio of roughly 10:1 or more, it may not be possible to maintain an industrial (as opposed to an agrarian) mode of societal organization over the long run.

A barrier stops oil coming ashore on June 5, 2010, in Grand Isle, Louisiana, after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. (Photo: Katherine Welles/Shutterstock)

NONE OF THE UNCONVENTIONAL sources that the petroleum industry is turning toward (tight oil, tar sands, deepwater) would have been developed absent the context of high oil prices, which deliver more revenue to oil companies; it’s those revenues that fund ever-bigger investments in technology. But older industrial economies like the U.S. and European Union tend to stall out if oil costs too much, and that reduces energy demand; This “demand destruction” safety valve has (so far) set a limit on global petroleum prices. Yet for the major oil companies, prices are currently not high enough to pay for the development of new projects in the Arctic or in ultra-deepwater; this is another reason the majors are cutting back on exploration investments.

For everyone else, though, oil prices are plenty high. Soaring fuel prices wallop airlines, the tourism industry, and farmers. Even real estate prices can be impacted: As gasoline gets more expensive, the lure of distant suburbs for prospective homebuyers wanes. It’s more than mere coincidence that the U.S. housing bubble burst in 2008 just as oil prices hit their all-time high.

Rising gasoline prices (since 2005) have led to a reduction in the average number of miles traveled by U.S. vehicles annually, a trend toward less driving by young people, and efforts on the part of the auto industry to produce more fuel-efficient vehicles.Altogether, American oil consumption is today roughly 20 percent below what it would have been if growth trends in the previous decades had continued.

We have extracted fossil fuels using the low-hanging fruit principle, going after the highest quality, cheapest-to-produce oil, coal, and natural gas first, and leaving the lower quality, more expensive, and harder-to-extract fuels for later. Now, it’s later.

To people concerned about climate change, much of this sounds like good news. Oil companies’ spending is up but profits are down. Gasoline is more expensive and consumption has declined.

There’s just one catch: None of this is happening as a result of long-range, comprehensive planning. And it will take a lot of effort to minimize the human impact of a societal shift from relative energy abundance to relative energy scarcity. In fact, there is virtually no discussion occurring among officials about the larger economic implications of declining energy returns on investment. Indeed, rather than soberly assessing the situation and its imminent economic challenges, our policymakers are stuck in a state of public relations-induced euphoria, high on temporarily spiking gross U.S. oil and gas production numbers.

The obvious solution to declining fossil fuel returns on investment is to transition to alternative energy sources as quickly as possible. We’ll have to do this anyway to address the climate crisis. But from an energy accounting point of view, this may not offer much help. Renewable energy sources like solar and wind have characteristics very different from those of fossil fuels: The former are intermittent, while the latter are available on demand. Solar and wind can’t affordably power airliners or 18-wheel trucks. Moreover, many renewable energy sources have a relatively low energy profit ratio.

One of the indicators of low or declining energy returns on energy investment is a greater requirement for human labor in the production process. In an economy suffering from high unemployment, this may seem like a boon. Indeed, here is an article that touts solar energy as a job creator, employing more people than the coal and oil industries put together (even though it produces far less energy for society).

Yes, jobs are good. But what would happen if we went all the way back to the average energy returns-on-investment of agrarian times? There would certainly be plenty of work to be done. But we would be living in a society very different from the one we are accustomed to, one in which most people are full-time energy producers and society is able to support relatively few specialists in other activities. Granted, that’s probably an exaggeration of our real prospects: At least some renewable energy sources can give us higher returns than were common in the last agrarian era. However, they won’t power a rerun of Dallas. This will be a simpler, slower, and poorer economy.

Transporting crude by rail. (Photo: Steven Frame/Shutterstock)

IF OUR ECONOMY RUNS on energy, and our energy prospects are gloomy, how is it that the economy is recovering?

The simplest answer is that it’s not—except as measured by a few misleading gross statistics. Every month the Bureau of Labor Statistics releases figures for new jobs created, and the numbers look relatively good at first glance (113,000 net new jobs for January 2014). But most of these new jobs pay less than those that were lost in recent years. And unemployment statistics don’t include people who’ve given up looking for work. Labor force participation rates are at their lowest level in 35 years.

All told, according to a recent Gallup poll, more Americans say they are worse off today than they were a year ago (as opposed to those who say their situation has improved).

Claims of economic recovery fixate primarily on one number: Gross Domestic Product, or GDP. That number is going up—albeit at an anemic pace in comparison with rates common in the 20thcentury; hence, the economy is said to be growing. But what does this really mean? When GDP rises, that indicates more money is flowing through the economy. Typically, a higher GDP equates to greater consumption of goods and services, and therefore more jobs. What’s not to like about that?

First, there are ways of making GDP grow that don’t actually improve lives. Economist Herman Daly calls this “uneconomic growth.” For example, if we spend money on rebuilding after a natural disaster, or on prisons or armaments or cancer treatment, GDP rises. But who wants more natural disasters, crime, wars, or cancer? Historically, the burning of ever more fossil fuels was closely tied to GDP expansion, but now we face the prospect of devastating climate change if we continue increasing our burn rate. To the extent GDP growth is based on fossilfuel consumption, when GDP goes up we’re actually worse off because of it. Altogether, Gross Domestic Product does a really bad job of capturing how our economy is doing on a net basis.

Second, a growing money supply (which is implied by GDP growth) depends upon the expansion of credit. Another way to say this is: A rising GDP (in any country with a floating exchange rate) entails increasing levels of outstanding debt. Historical statistics bear this out. But is any society able to expand its debt endlessly?

If there were indeed limits to a country’s ability to perpetually grow GDP by increasing its total debt (government plus private), a warning sign would likely come in the form of a trend toward diminishing GDP returns on each new unit of credit created. That’s exactly what we’ve been seeing in the U.S. in recent years. Back in the 1960s, each dollar of increase in total U.S. debt was reflected in nearly a dollar of rise in GDP. By 2000, each new dollar of debt corresponded with GDP growth of only $0.20. The trend line will reach zero in about 2016.

Meanwhile, it seems that Americans have taken on about as much household debt as they can manage, as rates of consumer borrowing have been stuck in neutral since the start of the Great Recession. To keep debt growing (and the economy expanding, if only statistically), the Federal Reserve has artificially kept interest rates low by creating up to $85 billion per month through a mere adjustment of its ledgers (yes, it can do that); it uses the money to buy Treasury bills (U.S. government debt) from Wall Street banks. When interest rates are low, people find it easier to buy houses and cars (hence the recent rise in house prices and the auto industry’s rebound); it also makes it cheaper for the government to borrow—and, in case you haven’t noticed, the federal government has borrowed a lot lately.

The Fed’s Quantitative Easing (QE) program props up the banks, the auto companies, the housing market, and the Treasury. But, with overall consumer spending still anemic, the trillions of dollars the Fed has created have generally not been loaned out to households and small businesses; they’ve simply pooled up in the big banks.Fed policy has thus generated a stock market bubble, as well as a bubble of investments in emerging markets, and these can only continue to inflate for as long as QE persists.

Oil drilling derrick. (Photo: James Jones Jr/Shutterstock)

The obvious way to keep these bubbles from growing and eventually bursting (with attendant financial toxicity spilling over into the rest of the economy) is to stop QE. But doing that will undermine the “recovery,” such as it is, and might even send the economy careening into depression. The Fed’s solution to this “damned if you do, damned if you don’t” quandary is to taper QE, reducing it gradually over time. This doesn’t really solve anything; it’s just a way to delay and pretend.

With money as with energy, we are doing extremely well at keeping up appearances by characterizing our situation with a few cherry-picked numbers. But behind the jolly statistics lurks a menacing reality. Collectively, we’re like a dietician who has adopted the attitude of the more you weigh, the healthier you are! How gross would that be?

THE WORLD IS CHANGING. Cheap, high-EROEI energy and genuine economic growth are disappearing. Rather than recognizing that fact, we hide it from ourselves with misleading figures. All that this accomplishes is to make it harder to adapt to our new reality.

The United States is where the oil business started and, in the past century-and-a-half, more oil wells have been drilled here than in the rest of the world’s countries put together.

The irony is, if we recognized the trends and did a little planning, there could be an upside to all of this. We’ve become over-specialized anyway. We teach our kids to operate machines so sophisticated that almost no one can build one from scratch, but not how to cook, sew, repair broken tools, or grow food. We seem to grow increasingly less happy every year. We’re overcrowded, and continuing population growth is only making matters worse. Why not encourage family planning instead? Studies suggest we could dial back on consumption and be more satisfied with our lives.

What would the world look and feel like if we deliberately and intelligently nudged the brakes on material consumption, reduced our energy throughput, and relearned some general skills? Quite a few people have already done the relevant experiment.

Take a virtual tour of Dancing Rabbit ecovillage in northeast Missouri. or Lakabe in northern Spain. But you don’t have to move to an ecovillage to join in the fun; there are thousands of transition initiatives worldwide running essentially the same experiment in ordinary towns and cities, just not so intensively.

All of these efforts have a couple of things in common: First, they entail a lot of hard work and (according to what I hear) yield considerable satisfaction. Second, they are self-organized and self-directed, not funded or overseen by government.

The latter point is crucial—not because government is inherently wicked, but because it’s just not likely to be of much help in present circumstances. That’s because our political system is currently too broken to grasp the nature of the problems facing us.

Quite simply, we must learn to be successfully and happily poorer. For people in wealthy industrialized countries, this requires a major adjustment in thinking. When it comes to energy, we have deluded ourselves into believing that gross is the same as net. That’s because in the early days of fossil fuels, it very nearly was. But now we have to go back to thinking the way people did when energy profit margins were smaller. We must learn to operate within budgets and limits.

This means decentralization, simplification, and localization. Becoming less reliant on long-term debt, paying as we go. It means living closer to the ground, learning general skills, and keeping a hand in basic productive activities like growing food.

Think of our future as the Lean Society.

We can make this transition successfully, if not happily, if enough of us embrace Lean Society thinking and habits. But things likely won’t go well at all if we continue to hide reality from ourselves with gross numbers that delay our adaptation to accelerating, inevitable trends.