This winter was brutal. Polar vortex brutal. My salt-caked boots and dry skin can attest to the frigid temperatures that covered more than 90 percent of the Great Lakes in ice. Much of that ice is still there—though some of it has run aground in an ice tsunami(!).

Over the decades, ice coverage on the lakes has been on the decline, but for the month of April, an average of 45 percent of lake surface remained ice-covered, according to the Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory. That’s nearly double the ice coverage of 1996, when the previous record was set, making April the iciest month since record-keeping began in 1973.

So what does this mean for the lakes themselves? Well, there are a few surprising outcomes of the lakes staying frozen so long (alas, none include a hit from Idina Menzel).

WATER LEVELS

The Great Lakes have been shrinking lately thanks, in part, to climate change. Last year, lakes Michigan and Huron hit their lowest levels since 1918, reaching an average of 29 inches below average. (The others are way below average, too.) The logic behind it goes something like this: Warmer winters mean less ice cover; less ice cover leads to warmer water temperatures; warmer water temperatures cause more evaporation.

The lakes “sweat” when they cool off, kinda like us, so a lot of the ice we saw this year formed from evaporating water.

This winter’s cooler temps will likely keep the water in the lakes for longer, possibly bringing them back to average water levels—at least temporarily. Predictions of how high the water may rise range from six to 20 inches. It’s hard (if not impossible) to predict how temperature and precipitation will factor in to lake levels. Even so, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has an official water level forecast.

FISHING

Cooler water temperatures will cause fish to migrate later in the season. Solomon David, a research scientist at Chicago’s Shedd Aquarium, told Michigan Public Radio that northern pike, lake sturgeon, steelhead, rainbow trout, yellow perch, and walleye will take longer to get to their spawning grounds. That’s because changes in water temperature and light prompt them to get a move on. If those signals get delayed, so do the fish. Unfortunately, if the fish lay their eggs later, their fry will hatch later and have less time to grow up … potentially making them more vulnerable to cold winters.

WILDLIFE

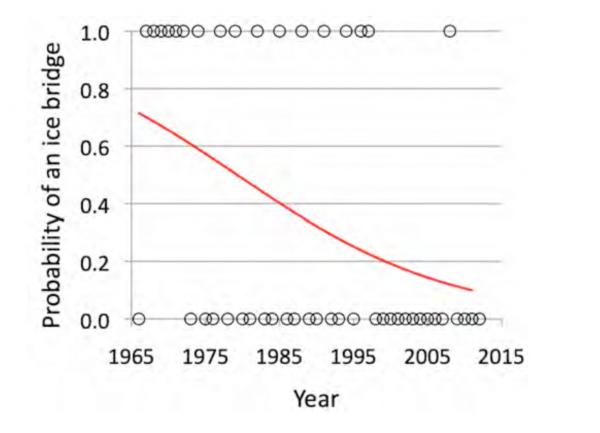

For the first time since 2008, an ice bridge formed to connect Michigan’s Isle Royale to the mainland. The likelihood of temperatures dipping low enough for an ice bridge to form like this are increasingly rare, but when they do happen wildlife like moose and wolves can cross between the island and mainland.

Researchers who have been observing the wolf-moose relationship on Isle Royale for more than 50 years were hoping that new wolves would cross over to boost the island’s population. Instead, a five-year-old female left the island and was later shot. (Sigh.) The good news is that during their annual winter survey, the researchers saw last year’s pups—and they were alive and well.

The recent National Climate Assessment explains in much greater detail how climate change is affecting the country, including the Midwest and its Great Lakes. And even though temperatures are rising in the region, there’s a higher likelihood of extreme weather events like those we saw this winter. So like a good Chicagoan, I’m cleaning off my boots and will be ready for future Arctic blasts. The cold never bothered me anyway.

This post originally appeared on OnEarth as “Frozen Spring” and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.