If a new scientific validation of one interpretation of a painting in Djehutihotep‘s elaborately decorated tomb is correct, then ancient Egyptians understood the key to king-sized desert Slip’N Slides.

The artistic commemoration that followed the Egyptian leader’s death is offering up clues, more than 4,000 years later, about how armies of men hauled hulking stones that were used to build the ancient pyramids.

Scientists who investigated the effect of potentially wetting sand in front of large Egyptian sleds—a process that may have been depicted on a painting in the nomarch’s tomb—say their discovery could have implications for how modern society can most efficiently transport everything from sand and cement to flour.

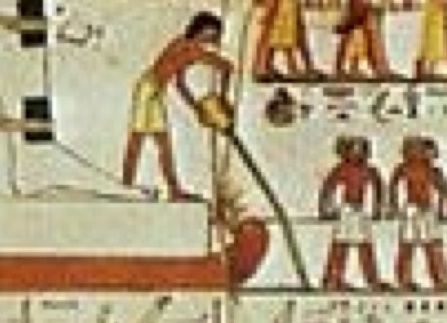

Check out this painting discovered more than a century ago in Djehutihotep’s tomb. It shows a giant statue of the leader being dragged on a sled, which was the same strategy taken for moving stones and other heavy payloads. Sometimes these sleds were dragged over wooden sleepers. But this scene might show something slightly different.

(Photo: P. E. Newberry, El Bersheh, The Tomb of Tehuti-Hetep, Vol. 1.)

Now, in this close-up, note the dude pouring what appears to be water over the sand ahead of the sled.

What’s he up to?

Some say the pouring was purely ceremonial. But after simulating the effect of moistening sand in front of an Egyptian sled in a laboratory, an international team of scientists has rejected that explanation. They say the water could have reduced the amount of friction between the wooden sled and the sand beneath it—a process they concluded may have halved the amount of horsepower required, which, back then, was measured as manpower.

“[I]n some cases the Egyptians built roads for the sleds out of wooden sleepers,” the scientists write in a letter published last week in Physical Review Letters. “The possibility of dragging the sled through desert sand is often precluded because it is believed to be too difficult. However, in view of our results, it seems very possible to drag the sleds over wet sand with the manpower available to the Egyptians.”

The scientists measured how much force was required to drag a weight-laden sled over miniature deserts, some of them damp and some of them dry. By adding a “small amount” of moisture to the sand that most closely replicated the Egyptian variety, the scientists hit a sweet spot: a friction coefficient for wood-on-sand that’s similar to that of wood-on-wood.

The scientists say that isn’t just fascinating from a historical perspective—it has ramifications for bulk commodity handling today.

“Most of civil engineering deals with the handling and transport of granular materials—sand, concrete, cement and so forth,” says Daniel Bonn, a University of Amsterdam professor who co-authored the new paper. “Slightly wet sand is transported more easily through pipes than dry sand. This is counter-intuitive, since the wet sand is harder.”