Shellfish are dying by the boatload, their tiny homes burned from their flesh by acid. Billions of farmed specimens have already succumbed to the problem, which is caused when carbon dioxide dissolves and reacts with water, producing carbonic acid.

When ocean life starts to resemble battery gizzards, how can humans possibly respond?

Immediately curbing the global fossil fuel appetite and allowing carbon dioxide-drinking forests to regrow would be obvious steps. But they wouldn’t be enough. Oceanic pH levels are already 0.1 lower on average than before the Industrial Revolution, and they will continue to decline as our carbon dioxide pollution lingers—and balloons.

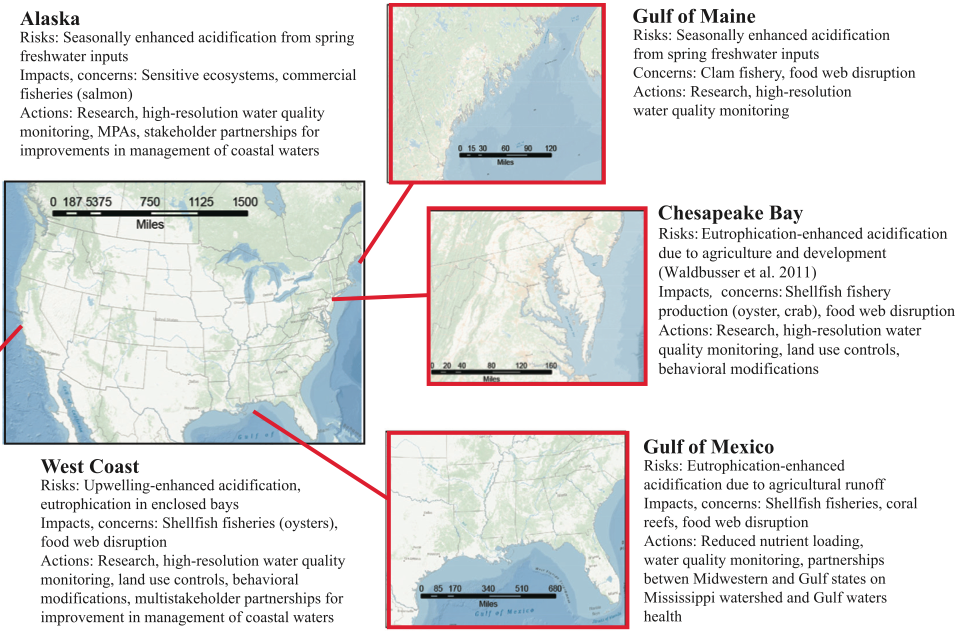

In a recent BioScience paper, researchers from coastal American states summarized what we know about ocean acidification, and described some possible remedies.

(Chart: BioScience)

As John Kerry kicks off two days of ocean acidification workshops, here’s our summary of the scientists’ overview:

WHAT WE KNOW

- Acid rain can affect ocean pH, but only fleetingly, especially when compared with the effects of carbon dioxide pollution.

- Studies of naturally acidified waters, like those near CO2 vents, suggest that acidification will depress species diversity; algae will continue to take over.

- Farm runoff and fossil fuel pollution can worsen the problem in coastal areas. The nitrogen-rich pollution fertilizes algae. That initially reduces CO2 levels, but the plankton is eaten after it dies by CO2-exhaling bacteria. This type of pollution appears to be worsening the acidification of the Gulf of Mexico.

- Strong upwelling, in which winds churn over the ocean and bring nutrients and dissolved carbon dioxide up from the depths, exacerbate local acidity levels in some regions. In the upwell-affected Pacific Northwest, climate change appears to be leading to stronger upwelling.

- Shellfish are “highly vulnerable” to ocean acidification. Some marine plants may benefit. Fish could suffer from neurological changes that affect their behavior. Coral reefs are also being damaged.

- Declining mollusk farm production could cost the world more than $100 billion by 2100.

- Marine plants can help buffer rising acidity. Floridian seagrass meadows appear to be protecting nearby coral.

WHAT’S BEING DONE

- The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration created an ocean acidification program in 2012. It’s monitoring impacts, coordinating education programs, and developing adaptation strategies.

- American experts are talking less these days about ocean acidification as a universal problem, and becoming more focused on local and regional solutions.

- Alaska, Maine, Washington, California, and Oregon have initiated studies and working groups.

WHAT MORE COULD BE DONE

- The EPA could enforce the Clean Water Act to protect waterways from pollution that causes acidification.

- Other coastal states could model new working groups on the Washington State Blue Ribbon Panel, which helped form the West Coast Ocean Acidification and Hypoxia Science Panel.

- Incorporate ocean acidification threats into states’ coastal zone management plans.

- Expand the network of monitors that measure acidity levels, providing researchers and shellfish farmers with real-time and long-term pH data.

- Expand marine protections to reduce overfishing and improve biodiversity, which can allow wildlife to evolve natural defenses.