(Photo: Kimberley Brown)

SINANGOE, Ecuador — The day begins with everyone drinking a big cup of Yoko. A man called Viejo (“old man,” in Spanish) carves the bark off a special vine found only in the Amazon highlands and mixes it with water. The resulting brew has a gritty texture and a bitter, earthy taste and gives the body instant energy that lasts for hours. After they drink, the indigenous Cofan guardia (Spanish for security force) grab their spears, backpacks, and GPS devices and head off to map their territory, deep in Ecuador’s Amazon rainforest.

Armed with machetes, two youth from the community chop through the thick jungle overgrowth to uncover the barely visible path. Suddenly Viejo stops; through the maze of trees and leaves some 20 meters off the trail, he sees the Yoko vine. Since the plant is sacred for the Cofan, they decide this deserves a point on the map.

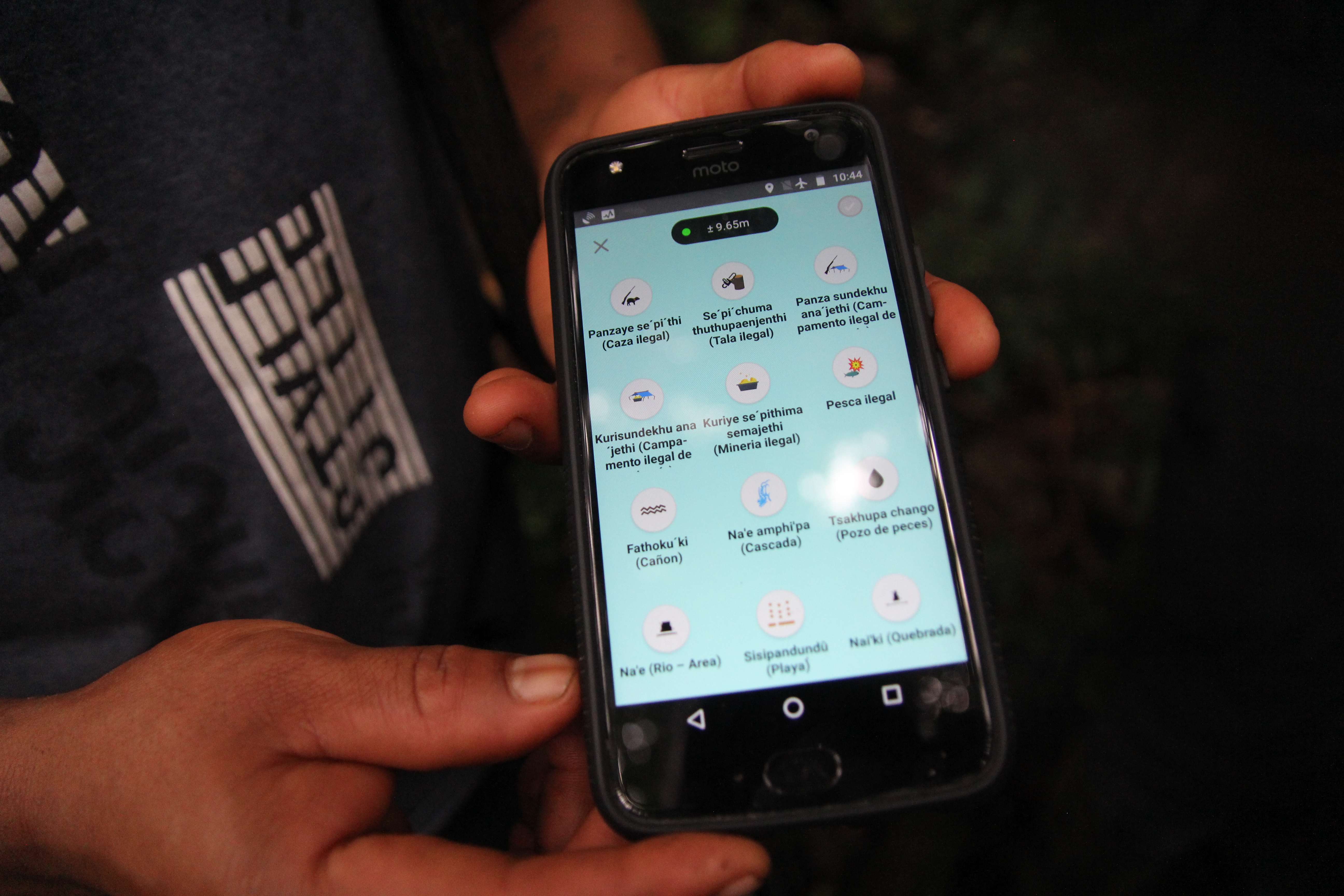

Edison Lucitante and Juan Herrera arrive with the technology. They both have GPS trackers in their pockets and cell phones, on which they use an application to help them document points of interest like this. Lucitante opens an application called Mapeo, selects the appropriate category for Yoko, types a short description of the plant, and takes a photograph.

“This is only found in certain areas. There’s almost none left,” Lucitante says about the Yoko vine. “That’s what I like most about the idea of mapping this information: Now we know exactly what’s inside our territory.”

(Photo: Kimberley Brown)

This is one of several excursions over the last three-plus months, during which the Cofan community of Sinangoe have been mapping their territory. The process began in January and will involve trekking through 55,000 hectares of mountainous, roadless terrain in the Amazon rainforest in the northeast of Ecuador.

Their goal is to use this map to demonstrate their ancestral connection with the land, and to establish standing to apply for an official land title. Such a document would finally allow the Cofan to have autonomy over their territory after years of fighting for land rights, and trying to fend off miners, poachers, and illegal loggers on their own.

Maps have historically been created by people in power and used as a way to claim land, to administer cities and nations, to enforce property rights, and to plot military strategies. But in recent years, marginalized communities around the world have begun to use new technologies to create their own maps and thereby demonstrate their deep local knowledge of their territories, which can help in their fight for land rights.

For the Cofan, this technology has already helped them win a landmark lawsuit against the Ecuadorian government last year. As a result of the suit, four different judges ordered that 52 mining concessions near their territory be canceled.

“Our worry is this that [developers] keep destroying what we have,” says Lucitane, who is also the current president of Sinangoe. “Every inch of our territory, every inch of our mountain is life for us,” he says.

Mapping a People’s Ancestry

There are some 40 families living in the community of Sinangoe today. They live in modest homes made from wooden planks, use medicinal plants when they get sick, and live largely off animals they hunt, fruits that grow in the rainforest, and community gardens where they grow plantains.

“We don’t live like they do in the city,” where people buy whatever they want, Lucitante says; for the Cofan, he explains, the rainforest is their hardware store, pharmacy, and supermarket. This knowledge about sustaining life and community in the forest was passed down from their ancestors, and the mapping process is therefore also an important way to preserve this knowledge for future generations, he says.

(Photo: Kimberley Brown)

There are currently 12 members of the Cofan guardia who have been trained in using the GPS and mapping applications, which were provided by the non-government organization Amazon Frontlines.

This relationship began in 2017, when the Cofan of Sinangoe approached Ceibo Alliance, an indigenous organization that partners with Amazon Frontlines, to ask for help in pushing illegal miners out of their territory. The two organizations helped the Cofan to create their own guardia, equipped them with a drone, hidden cameras, and GPS devices to track the illegal activity and create their own bylaw, warning miners to stay out. The bylaw is an extension of Ecuador’s program of indigenous justice, which is recognized both internationally and in Article 171 of the country’s constitution. The next step for the community is to apply for an official land title.

“We were there helping training and all that, but they’re the ones leading the process,” says Nicolas Mainville, environmental monitoring program coordinator with Amazon Frontlines, who has been working with the Cofan for the past two years.

Before the guardia began mapping their territory in January, the community sat down together to identify all the elements in the rainforest that are important for their sustainability, culture, and history. These include sacred sites, medicinal plants, animals in danger of extinction, fishing spots, special trees and vines, and more.

These elements were then used to create categories in a special mapping application called Mapeo, designed by Digital Democracy, a California-based non-profit organization that teaches marginalized communities to use technology to defend their rights. When the guardia goes into the jungle to map, these categories are what they’re looking for.

Aliya Ryan, program director with Digital Democracy, says Mapeo was designed to be easy to use and is available in A’ingue, the Cofan’s native language, which means members of the community can use it on their own. This functionality is what sets Mapeo apart from other, more complex GIS mapping software, Ryan says.

Why Land Titles Are So Important to Indigenous Peoples

Brian Parker, one of the Cofan’s legal advisers with Amazon Frontlines, explains that mapping is an essential tool for applying for land rights, as the Cofan need to prove three things: that they have an ancestral connection to the land, that this connection is ongoing and necessary for their cultural survival, and that they currently exercise control and vigilance over that territory.

The Cofan have been living in the northeast of Ecuador for thousands of years; anthropologists estimate that over 30,000 were here during the first Spanish conquest in the 16th century. By 2014, that number had dropped to 1,400, a much-diminished community that nevertheless maintains a strong connection to the rainforest. According to Article 26 in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, these considerations are enough for the Cofan’s land to be recognized as ancestral territory.

(Photo: Jeronimo Zuniga/Amazon Frontlines)

But Ecuadorian policies directly contravene these U.N. directives. Today, the Cofan of Sinangoe’s territory lies within a national park, the Cayambe Coca Ecological Reserve, and technically belongs to the government. This arrangement puts limits on the community’s autonomy and obliges them to abide by the province’s conservation regulations, Mainville says. These include things like caps on hunting and the requirement that the Cofan seek permits before cutting down trees for community use, among others.

And being within the park’s boundaries has not been enough to protect the region from environmental threats either.

Over the past two years, the Cofan have been battling an influx of gold mining operations along the Aguarico river, upstream from Sinangoe, within their territory and the national park. The community had reported these activities and its dire environmental impacts to the Ministry of Environment several times, but these complaints all went ignored, members of the Cofan say.

That’s when the community approached Ceibo Alliance, which, in 2017, helped the Cofan create their own bylaw that warns miners and other trespassers to stay out of their territory. For the most part, this move brought the illegal mining to a halt—for a while.

But in 2018, the mining threat resurged, as miners gained legal concessions and stepped up their operations with bigger machinery and more voluminous toxins, such as the cyanide they use to separate gold from sand. These miners received permits from the Ministry of Mining, but never underwent a proper consultation process with the community, which is required by both national and international law, according to the community’s lawyers. With the help of Amazon Frontlines and the Ecuadorian Ombudsman, the Cofan decided to sue four government bodies and associations (the Ministry of Mining, the Ministry of Environment, the Mining Regulation and Control Agency, and Ecuador’s National Water Secretariat) for allowing the operations to continue, and for not applying sanctions.

Using their new monitoring technology, the Cofan collected enough evidence that these miners had been operating outside their concessions, destroying the riverbank and contaminating the water, to win the case. One regional judge initially ruled in favor of the community, saying that the government had violated their rights as well as the rights of nature. A provincial tribunal, from the province of Succumbios, extended that ruling on appeal and ordered that 52 mining concessions along the Aguarico river be canceled.

“On the legal side, it’s so useful to have maps” and to work with GPS technology, Mainville says, adding it empowers communities to collect concrete information that can’t be distorted or dismissed. “You can’t really corrupt GPS,” he says.

Today, the guardia continues to monitor their territory and make sure the courts’ recent rulings are observed, but the Cofan remain equally focused on the mapping.

“Today, we feel stronger and more powerful and able to say that the Cofan are warriors. We won the trial. We beat the government,” Lucitante says. “We’re going to keep going.”