It’s not easy to protect an environment that doesn’t yet exist from threats that have not yet materialized.

Yet that’s what we need to do in the Arctic, where a development and shipping boom is looming as the region is reshaped by the melting of economic-obstructionist ice.

The embryonic scramble for new shipping channels, oil fields, fisheries, tourist meccas, and port cities has governments, including Russia and the United States, worried enough to begin preparing to send in their militaries. It also has scientists worried—worried that an uncoordinated development boom will lead to oil spills, accidents, pollution, and bright lights that kill, drive away, and disorient wildlife in what now is a nearly environmentally pristine swath of the planet.

“Findings from this work could be used, at the very least, to define areas of extreme importance, where ships would be banned from purging bilge tanks or dumping of any sort.”

“In an ideal world, there would be no shipping in the Arctic,” says Grant Humphries of the University of Otago’sCenter for Sustainability in New Zealand. “But, clearly, the drive of economic powers will lead to shipping.”

There’s nothing static about the amount of sea ice surrounding the North Pole. It ebbs and flows with the seasons, and wildlife arrive and depart accordingly. Sea ice bottomed out in mid-September at two million square miles, and it topped out in March at nearly six million square miles. Overall, though, climate change has caused ice levels to decline by a few percent per recent decade. Different researchers have made different predictions for when it will disappear during summers. Some say that will take a few more years; others say it will take decades.

To protect a marine environment, scientists look for hotspots where wildlife gathers, breeds, and feeds. Government officials balance that data with business priorities as they craft protected areas and environmental regulations. But protecting the open waters of the High Arctic of the future is not so easy. As the ice layers shrivel, wildlife will find new places to congregate, often near shifting shorelines, and legitimate businesses and pirate operations alike will find new places to set up shop.

Humphries and a colleague wanted to know the locations where seabirds would congregate near shipping and development areas. Because they don’t know where seabirds will gather in the future, they compared data sets of existing seabird density for 27 species with maps showing nascent Arctic commercialism.

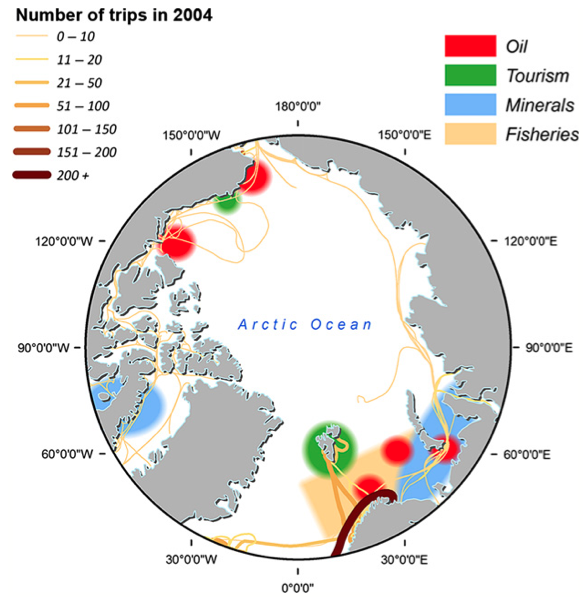

Here’s the map of commercial activity:

(Map: Diversity and Distributions)

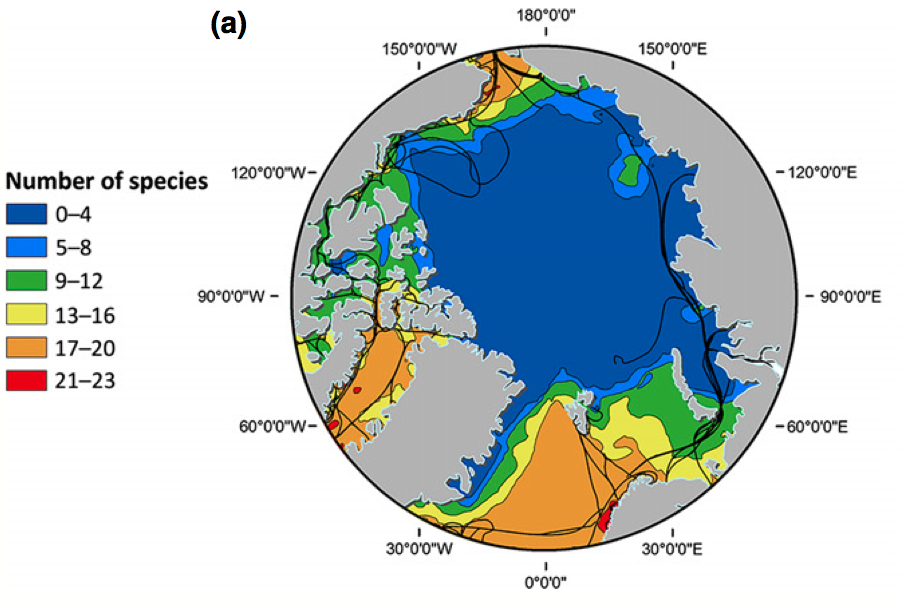

And here’s the map of seabird diversity, overlaid with the information about shipping lanes:

(Map: Diversity and Distributions)

The scientists wrote in a recent Diversity and Distributions paper that they found “quite high” overlaps between commercial activity and seabirds. In some cases, 85 percent of the 27 species frequented developing areas. In the Norwegian and Barents Sea, they found “relatively high amounts of fishing activities, shipping activity and shipping accidents” in hotspots of seabird biodiversity.

“Findings from this work could be used, at the very least, to define areas of extreme importance, where ships would be banned from purging bilge tanks or dumping of any sort,” Humphries says. “Marine protected areas should be defined.”