The molasses killed by suffocation, mostly.

When the Purity Distilling Company’s 2.3-million-gallon storage tank in Boston’s North End suddenly collapsed on January 15th, 1919, the streets of Boston immediately became a horrifying, inescapable morass of sticky death. Witness accounts described a wave of molasses between 15 and 25 feet high bearing down on shocked passersby; people “were picked up by a rush of air and hurled many feet,” according to a contemporaneous report from the Boston Globe. It was a shocking and horrific death for the 21 unlucky individuals who were killed.

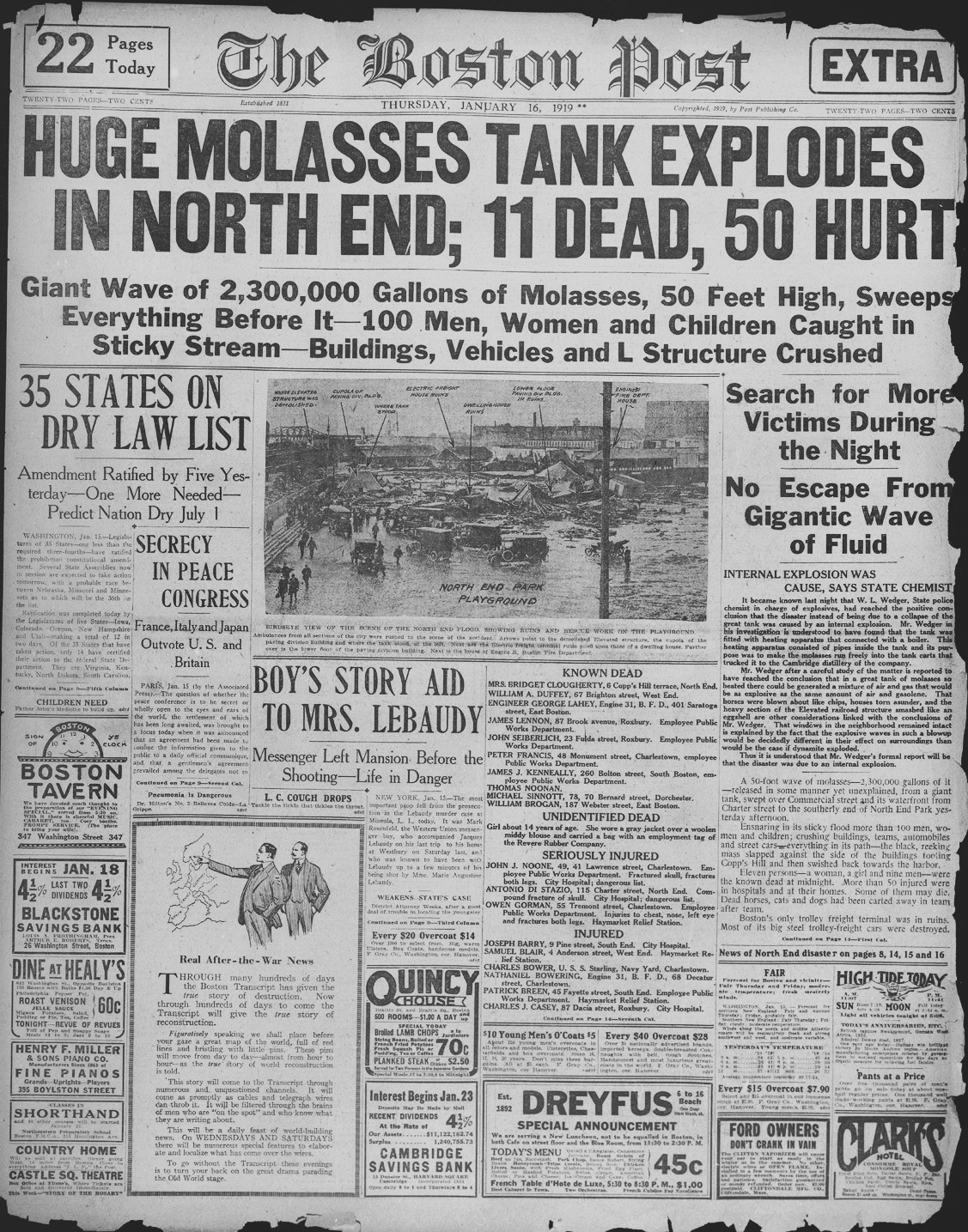

“Here and there struggled a form—whether it was animal or human being was impossible to tell. Only an upheaval, a thrashing about in the sticky mass, showed where any life was,” the Boston Post reported at the time. “Horses died like so many flies on sticky fly-paper. The more they struggled, the deeper in the mess they were ensnared.” One young boy headed home from school “was picked up by the wave and carried, tumbling on its crest, almost as though he were surfing,” as Smithsonian reported in a 1983 history of the deluge. “He heard his mother call his name and couldn’t answer, his throat was so clogged with the smothering goo.”

(Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Historically, we tend not to remember the Boston Molasses Disaster, which turns 100 this month, as much more than a freak accident. According to a 2011 examination by the National Fire Protection Association Journal, explanations for the collapse range from observed structural weaknesses to rapid temperature changes due to a recent delivery of hot molasses. As far as industrial disasters go, the 21 fatalities of the Boston Molasses Disaster may seem low; the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire that occurred in New York City eight years prior left 146 dead from suffocation and smoke inhalation.

But fame (or lack thereof) aside, the Boston Molasses Disaster still marked a major moment in American public policy. It led to a shift in how cities and states evaluated and regulated construction standards, first in Massachusetts and them nationwide, triggering the sudden promulgation of requirements and restrictions governing the concrete and steel that American cities are made of. And, more importantly, it made regulation a tool of the taxpayer, rather than the mere inconvenience it had previously been for business magnates.

The disaster, as one historical website put it, “marked the beginning of the end of an era when big business faced no government restrictions on its activities—and no consequences.”

In the immediate aftermath of the disaster, some 120 lawsuits involving victims of the incident were rolled into a class-action suit against Purity Distilling Company and its parent company, United States Industrial Alcohol. The resulting investigation, which lasted six years and included testimony from more than 3,000 witnesses, proved disastrous for the alcohol distributor: USIA was shown to have “engaged no one with any engineering or architectural expertise to review the plans created by Hammond Iron Works, either in the planning stage or after construction, nor had they asked other experts inside USIA to analyze the construction,” according to a remarkably deep look at the legal proceedings published by the Daily Kos. Not only did USIA fail to conduct regular inspections of the tank during and after construction, but the company’s leadership summarily ignored concerns from both inside and outside the organization regarding the safety of the project.

Here’s more, per the Daily Kos:

The company had selected the site purely on its proximity to the wharfs without regard to the dense population in the area, he found. It had placed a man in charge with no engineering or construction experience who neglected to take basic measures to insure a proper factor of safety was provided in the design and construction of the tank, neither retaining nor consulting qualified engineering professionals to create or review plans, failing to carry out proper inspections, failing to test the receptacle when completed, and ignoring (and even concealing) concerns about the tank’s safety after it was filled.

The sheer amount of negligence, both deliberate and otherwise, was recorded for the plaintiffs in painstaking detail by attorney Damon Hall. But, as the Daily Kos details, USIA defense attorney Charles Choate fabricated a story blaming the disaster on Italian anarchists. (The explanation was actually somewhat plausible, if not credible: Anarchists had targeted USIA facilities on the East Coast during World War I.) Choate’s case was designed to prey on Boston-area paranoia over the activities of Italian anarchists on the wharfs. (It wasn’t really because they were anarchists, per se: The close of World War I and the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia had ushered in the “Red Scare” in modern American history; in Boston, that anxiety would focus on Italian immigrants, culminating with the controversial executions of Italian-born anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti in 1927.)

Bolstering Choate’s efforts was the fact that the disaster struck at a time when the Supreme Court was already pushing a lax legal and regulatory environment for businesses, wherein companies could effectively count on avoiding liability or responsibility in the courtroom. And it’s worth noting that such paranoia and a laissez faire attitude toward business would likely have played out without one bit of historical contingency: the appointment of Colonel Hugh W. Ogden as the auditor to oversee the lawsuit by the Massachusetts Superior Court.

“Ogden, as a soldier and a patriot, would have despised both the motives and methods of the anarchists. And, as a conservative businessman, he more than likely shared USIA’s concern about excessive government regulations and interference,” wrote historian Stephen Puleo in Dark Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919. “But Ogden had a deeper set of beliefs, and they were grounded in a sense of fairness and justice.”

Ogden’s steady hand delivered a major rebuke to USIA—and the U.S.’s business community more broadly. In 1925, Ogden found USIA fully at fault for the incident, forcing the company to pay out an eye-popping $7 million in settlements. The flood and subsequent court decisions “marked a symbolic turning point in the country’s attitudes toward Big Business, which for most of the first quarter of the twentieth century had been subjected to few regulations to safeguard the public,” Puleo wrote in Dark Tide. With Ogden’s guidance, the victims of the Boston Molasses Disaster proved that the modern American regulatory regime was strong enough to actually hold businesses accountable.

“After the molasses hearings, despite continued economic prosperity and a strong pro-business attitude in Washington, the public began to fight back,” Puleo added. “Hugh Ogden’s strong language and clear verdict against USIA in 1925 showed that the country had come a long way in ten years; a corporation could be made to pay for wanton negligence of the sort that led to the construction, with virtually no oversight or testing, of a monstrous tank capable of holding 26 million pounds of molasses in a congested neighborhood.”

Regulations are only as strong as their enforcement; the Ogden ruling showed that, at least in Massachusetts, they had teeth. And for the first time in recent memory, it was the public, rather than profits, that won.