From the back of the police car, I looked out into dense smog. The air quality was so bad I couldn’t see the Wasatch Mountains that hug Salt Lake City. During wintertime inversions, cities along the Wasatch Front often have the worst air quality in the nation, as emissions released from cars and refineries get trapped in cold air near the ground. Now, with wildfires across the West during the summer, Salt Lake rarely gets a reprieve from air pollution. It felt dystopian: I was getting arrested for protesting fossil fuel extraction while the air outside was verifiably unhealthy to breathe.

A few hours earlier, on the morning of December 10th, I had walked with 15 other young people into the Utah Bureau of Land Management Office. We were there to protest the agency’s December of 2018 oil and gas lease sale, during which 150,000 acres of public lands in Utah were auctioned off.

We carried a letter with over 150 signatures and 80 personal comments—but before we handed them over, we intended to read the messages aloud.

Utah has a history of civil disobedience in protest of the BLM’s oil and gas sales. A decade ago, Tim DeChristopher raised his Bidder 70 paddle, shutting down an auction of land near Arches and Canyonlands national parks. A wave of protests continued until the in-person lease sales were moved online in 2016. Since the Trump administration has increased oil and gas leasing, young organizers decided it was time to show up at the BLM office once again to make ourselves heard.

Two of my friends unfurled a massive banner on which the text of the letter was written. Others held a banner that read Defend Our Future and Sacrifice No More around a painting of water flowing from snow-peaked mountains through red rock cliffs and into cupped hands. Our voices echoed through the office as we collectively recited the opening of our letter: “We are writing in protest of the immoral and irresponsible sale of public lands, which are stolen indigenous lands, for oil and gas extraction….”

We then took turns reading comments from grandparents and students, doctors and Ute elders. Messages centered on two main issues: climate change and public input.

“Climate change is a real force that is beginning to alter our world in shocking ways,” wrote Sarah Stock, a Moab, Utah-based organizer with Canyon Country Rising Tide. “We can see it from the 19-year drought in the Colorado River Basin to the mass die-off of mountain forests and intensified wildfire seasons.”

The National Climate Assessment, which the Trump administration released on Black Friday in 2018, predicts a devastating future for the United States, including mass wildfires and dramatic decreases in crop yields. Extreme drought has already hit Utah, and 2018 was the state’s driest year on record. To prevent catastrophe, scientists with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change say that nations must transition away from fossil fuels in the next 12 years. Many messages to the BLM emphasized the agency’s role in such a transition, as a recent report released from the U.S. Geological Survey says fossil fuels extracted from public lands account for one-quarter of U.S. carbon emissions.

“There has been too much careless and willful destruction of these, our lands,” commented Forrest Cuch, a Ute Elder on the Uintah and Ouray Ute Reservation. “Stop contributing to rising temperatures on our planet due to excessive fossil fuel development.”

Under the Trump administration, the BLM has ramped up lease sales. In total, the Utah agency offered more than 420,000 acres for sale to the oil and gas industry in 2018, including some of the largest sales since the George W. Bush administration.

This recent increase in oil and gas leasing followed an “instruction memorandum” issued in January of 2018, which directed BLM field offices to accelerate oil and gas leasing. To do this, the agency curtailed environmental review and eliminated public comment periods, which are mandatory under the National Environmental Policy Act, the Federal Land Policy and Management Act, and the BLM’s own oil and gas leasing policy.

For the December sale, the BLM shortened the usual 30-day commenting period to a 15-day “scoping period.” No environmental analysis was made available for review. In addition, the official “protest period” was shortened from 30 days to 10. During protest periods, individuals with either a stated interest in specific parcels or representatives of organizations can hand-deliver, fax, or snail-mail a letter in protest. There is no electronic submission option.

These letters are challenging to turn out en masse, as they must be individual and require technical expertise. “I have a hard time understanding the lease on my house, let alone a government lease for oil and gas,” one Salt Lake City-based organizer said during a planning meeting for the action.

A protest letter submitted by environmental groups said, “This truncated opportunity for public participation is illegal.” Their claim was backed up in court: A lawsuit filed by Western Watersheds Project and the Center for Biological Diversity in April of 2018 challenged the BLM’s inclusion of sage grouse habitat in oil and gas lease sales. This forced the Utah BLM to move 174,986 acres of sage grouse habitat from the December of 2018 sale to the March of 2019 sale. In addition, a preliminary injunction found that the BLM had illegally reduced public commenting. The agency reestablished a 30-day commenting period for the March sale, but all other sales in 2019 so far have reduced commenting periods.

“In their failure to provide an accessible commenting period, the BLM has disregarded members of the public already intimately impacted by climate change,” said Eliza Van Dyk, a Westminster College student and climate justice organizer. “Continued oil and gas leasing shows that the Trump administration doesn’t value the lives of people on the frontlines of climate disaster.”

The letters we delivered were symbolic in nature, meant to highlight how the agency has made public participation in the oil and gas sales inaccessible. Even though the BLM told us they would file these letters, we knew the chances they would listen to our demands and stop the sale were low. We were delivering them past the end date of the official “protest period,” and most letters didn’t represent organizations or express a stated interest in specific parcels. Instead, our messages were in protest of the entire process.

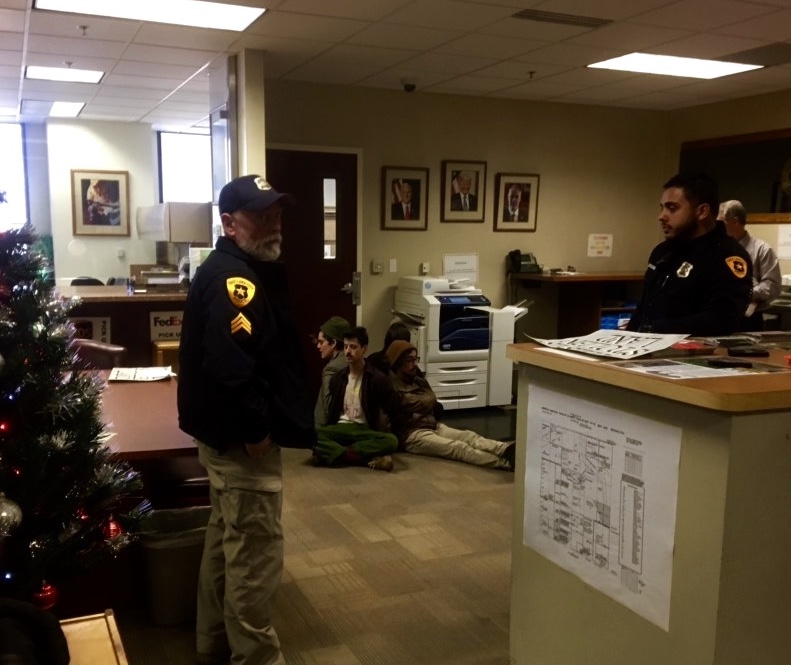

(Photo: Natascha Deininger)

We continued to read the letters aloud and sang protest songs such as, “People gonna rise like the water/we’re gonna face this crisis now/I hear the voice of my great granddaughter/saying keep it in the ground.” The staff became increasingly irritated, and repeatedly asked us to leave. About an hour into the sit-in, security told us to disperse.

When the Salt Lake County Police arrived, most people left, but four of us sat in a circle, linked arms behind our backs, and announced that we would leave once the BLM agreed to cancel the sale. Since a judge asserted that the BLM had illegally reduced opportunities for public participation, we felt we had a right to protest the sale.

The number of police in the room increased over the next hour, and the BLM showed no sign of agreeing to our demands. BLM staff collected the remaining letters that lay across the office lobby, and the police arrested us.

When we were released from jail in the evening, the smog had worsened. My initial relief to be outside was tainted by the taste of toxic air. I started humming the song that had been playing on repeat in my head: “We’re gonna rise up, rise up ’til it’s won/When the people rise up, then the powers come down/They tried to stop us, but we keep coming back.”